European elections 2019: How does voting work?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore than 400 million people are eligible to vote in this month's European Parliament elections, in one of the biggest democratic exercises in the world. So how do you hold a vote in 28 different countries under a whole host of different rules?

In the last election in 2014, 168,818,151 people took part, with a turnout of just over 40%, and five million ballots were spoiled.

That makes it bigger than the US presidential vote, though not even close to the size of India's election, which is the largest.

This year's elections are taking place over four days with three voting systems, but it all comes together thanks to a set of common principles- and the willingness of member states to tweak their national election rules to suit.

Here's how it all works.

When is the vote?

Voting takes place across three days, depending on where the election is being held.

- 23 May: Netherlands, UK

- 24 May: Ireland, Czech Republic (which has two-day voting also on 25 May)

- 25 May: Latvia, Malta, Slovakia

- 26 May: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden

Voting times vary from country to country, in line with local customs. And each country elects a different number of MEPs, roughly in line with their population – so France (74) and the UK (73) have more seats than Ireland (11) or Latvia (8).

And for some, voting is compulsory so there's no escape - in Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Greece, and Luxembourg.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCounting is also done on a country-by-country basis – but the results are kept secret until all voting is finished.

The results will be announced from 23:00 Brussels time (22:00 BST) on Sunday, 26 May, so that the announcement of results from the UK or other early voting countries cannot affect voters somewhere else.

What system is used for voting?

Every country is free to use its own system for voting, and there are plenty of differences.

The voting age, for example, is set by national law. And there is some sort of postal or proxy system in place everywhere except Czech Republic, Ireland, Malta, and Slovakia.

Most countries elect their MEPs in one single big national constituency - so Germany has, for example, 96 German MEPs. But a handful – Belgium, Ireland, Italy, Poland, UK – have multiple constituencies.

The most important common rule, however, is that countries must use a proportional system.

This is different from the first-past-the-post system used by the UK in its national elections (the only EU country to do so). So the UK has to change its voting system to a more representative model for EU elections.

In effect, there are three systems in use:

Closed lists

- Used by: UK (except Northern Ireland), Portugal, Spain, France, Germany, Romania, Hungary

In a closed-list system, political parties make a list of their candidates in order from top to bottom preference. Voters then vote for the party they like – but they cannot vote for an individual person or affect the order of the people on the list.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDepending on the results and the amount of seats available, seats are handed out to the people on the list in order of preference. So the top party list might get its top two or three people elected, the second-place may get one or two, and so on.

The exact distribution method depends on the country. The UK uses something called the D'Hondt method to figure out how to allocate seats; a similar but slightly different system called the Sainte-Laguë method is used in Germany and some other countries.

The general principle, though, is that the party with the most votes should get the most seats – and who in the party gets those seats is decided by the party leadership.

Preferential lists

- Used by: Finland, Sweden, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Austria, Slovenia, Croatia, Bulgaria, Greece, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Poland, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, Denmark

Preferential lists or "open lists" are very similar to the closed list system detailed above, except that voters can influence which individual person wins a seat by affecting the order of people on a list. Exactly how much influence the voter has on the order of candidates varies from country to country.

Generally, voters pick a candidate to vote for and their vote counts for both the party and that individual person. If the candidate gets a significant number of votes, they may be elected ahead of higher-placed people on the list.

Some countries give a few "preference votes", others just one; some countries allocate seats based on the number of votes; others only guarantee a seat if a candidate beats a certain target such as winning 5% or 10% of all votes.

Single Transferable Vote (STV)

- Used by: Ireland, Malta, Northern Ireland

Proponents of STV claim it is the most representative system, but it is only used by a handful of countries in European elections.

On the ballot paper, voters vote for the candidate they like best by writing the number "1" in a box. They then vote for their second-favourite as number "2" and so on – for as many or as few people as they like with no restrictions.

When it comes to counting the votes, organisers first figure out what the election "quota" is. If there are four seats and 100,000 people cast a vote, then the quota would be 100,000 divided by five, plus one - or 20,001.

The reason for the maths is that only four people could possibly achieve this number of votes. Four times 20,001 is 80,004: there would be just 19,996 votes left - not enough to reach the quota. The formula works for any number of seats (just divide the total votes by the number of seats plus one), and any number of votes.

Getty Images

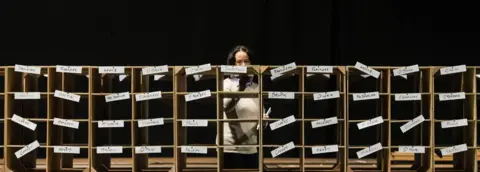

Getty ImagesSo the votes are all counted, and if someone reaches the quota, they are elected. If they do not, the worst performer is eliminated - and all their votes are redistributed to the second-place preference on each ballot paper.

When someone is elected, any extra votes they have that don't matter (because they already reached the quota) are likewise re-distributed. This is the transferable part of the single transferable vote.

The idea is that every vote is counted towards someone, and that no vote is wasted on obvious winners or losers. It is, however, much more complicated to count.

What are electoral thresholds, and which countries have them?

Some countries have an electoral threshold - where, by law, a party or a candidate needs to gain a certain percentage of the national vote to qualify for a seat. The idea is to prevent very small, fringe, or extremist parties from winning seats without meeting a minimum level of support - usually a small percentage.

France, for example, is a single constituency with 74 seats - so, without a threshold, it would take just 1.4% of the vote to win a seat. But France has set its minimum threshold at 5%.

The countries where thresholds apply for the 2019 elections are:

- 5%: France, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Romania, Croatia, Latvia and Hungary

- 4%: Austria, Italy and Sweden

- 3%: Greece

- 1.8%: Cyprus