INF treaty: Putin shrugs off Trump’s nuclear arms move

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWaking up to daily headlines about nuclear obliteration is not a comfortable feeling. But Vladimir Putin seems to be relishing an exchange of deadly threats with the United States.

As Donald Trump tears up a key arms control treaty and pledges to rebuild his country's nuclear arsenal, Russia's president has promised to mirror every move.

Last week, he even joked about nuclear Armageddon.

Military might has become key to Mr Putin's positioning of Russia as a country to reckon with: no longer a superpower like the USSR, but still a nuclear force and one with its own agenda and interests to defend.

So the fact that the INF treaty is now close to tatters apparently suits Moscow just fine.

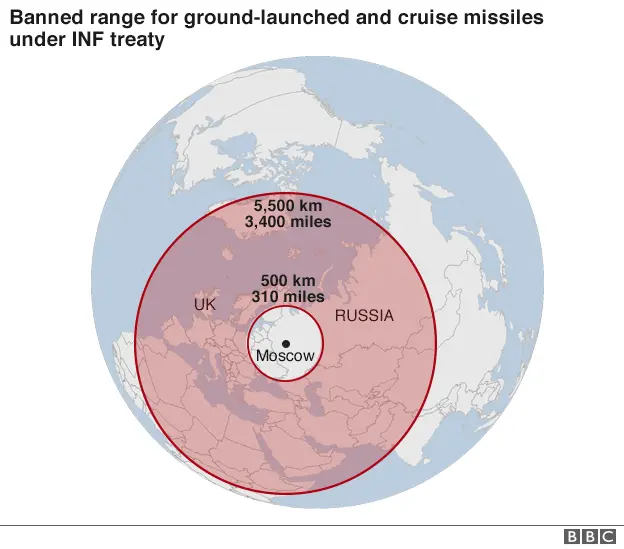

Signed in 1987 by the then Soviet and American leaders, the landmark agreement eliminated a whole class of ground-based missiles capable of hitting targets in Europe at a moment's notice.

Now the US is scrapping the deal, Mr Putin has warned European nations that they'll be thrust back into the firing line as Moscow and Washington rearm.

But Mr Putin was boasting of Russia's nuclear might even before Mr Trump's announcement.

Last week, he was guest speaker at the annual Valdai Discussion Club in the mountains above Sochi.

Once a forum for the president to be grilled by Russia experts from abroad, the "club" is now distinctly lacking in bite.

AFP/Getty

AFP/GettyThis year, frankly, Mr Putin seemed bored. At one point he remarked that he would like to end the event soon, as he had a hockey game to get to.

But he did perk up significantly over one issue: nuclear weapons.

Hit us, we hit back

Brushing off Western accusations from election meddling to targeted assassination like annoying flies, Mr Putin told his audience that Russia feared nothing and nobody.

That confidence, it transpired, stemmed mostly from Russia's nuclear might.

Mr Putin vowed that Russia would never carry out a first nuclear strike.

But hit us, he warned any potential aggressors, and we'll hit back.

His statement then morphed into a dark joke.

As Russians would be the victims of such a strike, Mr Putin argued, they would be "martyrs and go to heaven, whilst [the aggressors] would just croak. Because they wouldn't even have time to repent".

The end-of-the-world quip tripped easily off his tongue, to be met by a burst of approving chuckles.

"It's impossible to imagine [Soviet President] Brezhnev making that kind of joke in the 1960s," one foreign policy analyst back in Moscow pointed out.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe problem with all the war talk, Andrei Kortunov suggested, is that politicians on both sides have lost their terror of a nuclear strike. That fear ended, he thinks, with the Cold War.

"They just don't believe it will ever happen now," Mr Kortunov said.

'Much worse than Cold War'

To many commentators here, a new rush to arm to the teeth looks inevitable as the INF agreement crumbles - something many in the Russian military will be pleased about.

"They criticise Mikhail Gorbachev as a traitor who was fooled by the Americans into a terrible treaty that deprived the USSR of its most important weapons," says Victor Mizin, an arms control expert who worked on the original deal during the 1980s.

"At a certain level, those negative feelings are quite strong," he adds. But as someone who describes the INF treaty as very close to his heart, he's concerned.

Russian Defence Ministry

Russian Defence Ministry"As an old Cold War warrior, I think the situation psychologically is much worse now than in the Cold War," Mr Mizin worries. "There was more predictability and more respect then."

That goes for both sides.

There may be one restraining factor for Russia: there is no bottomless pit to mine for funds.

Whatever the bluster about coping under Western sanctions and a sunken oil price, budgets here are already under strain. Raising the pension age to cut costs has already sparked protests and caused Mr Putin's approval rating to drop.

But that may not worry Russia's president too much.

There was another of his comments from the Valdai discussion that stood out: his talk of a lack of fear when taking risk. Mr Putin said he learned at spy school that the cause always took precedence over self-preservation.

As president, he sees his cause as restoring Russia to its status as a global power. He looks set to go nose-to-nose with the United States in a risky new nuclear arms race to do that.