Chemnitz protests: Far right on march in east Germany

EPA

EPAOn an overcast afternoon, small candles flicker on the paving stones where, in the early hours of Sunday morning, a German carpenter in his thirties was fatally stabbed in a street fight.

Even now, complete strangers arrive to lay flowers, stand in silence, hold hands. This growing makeshift memorial has become a focus for this troubled city's grief and anger.

Little is known about how or why the brawl started. Police have dismissed rumours circulating online that the man was defending a woman from sexual assault.

But within hours of his death in hospital, news that his killers were suspected to have been a Syrian and an Iraqi man triggered a furious and violent reaction.

For two nights running, hundreds and then thousands of right-wing extremists and sympathisers have taken to the streets.

The police openly admit they have been caught on the back foot both by the number of protesters and the speed at which they have mobilised. The groups behind the demonstrations have used social media to bring people together quickly.

On Monday night in particular, organisers were able to galvanise supporters from all over the country.

The seemingly spontaneous outbreak of violent xenophobia has shocked many in Germany.

Pictures of demonstrators openly using the Nazi salute - a criminal offence in Germany - chasing and attacking people of foreign appearance and flinging bottles and fireworks have horrified many Germans, for whom the legacy of World War Two is a lasting belief that this country bears a special responsibility to fight any form of fascism.

But many are not surprised.

How big is the far right in the east?

Right-wing sentiment and extremism have tended to find more fertile ground in Germany's former east - fuelled, some argue, by the social and economic inequality that followed reunification.

Associated violence was much higher last year for example in this part of the country than the west.

The head of Saxony's intelligence services, Gordian Meyer-Plath, has said there is an organised scene in Chemnitz that includes right-wing hooligan structures such as the "NS boys" or "Kaotik Chemnitz" - organised around their support for the local football club.

Both groups took part in the weekend's demonstrations.

The intelligence services reckon there were just over 23,000 right-wing extremists in Germany in 2016.

German authorities have now vowed to intensify their efforts in the fight against them.

But people who would describe themselves as ordinary citizens joined the demonstrations in Chemnitz, too.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSince 2015, when hundreds of thousands of people sought asylum in Germany, anti-migrant sentiment has manifested much more strongly in the old east.

Anti-migrant grassroots movement Pegida harnessed public concern in Saxony with weekly marches in Dresden, which at their height attracted 20,000 people.

Some were extremists. But all marched together, chanting the old Nazi slogan "Lügenpresse" (lying press).

Pegida also encouraged demonstrations in Chemnitz at the weekend, but it is no longer the force it was.

Hard on its heels came the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) party.

AfD goes from strength to strength

Saxony may have encountered relatively few asylum seekers.

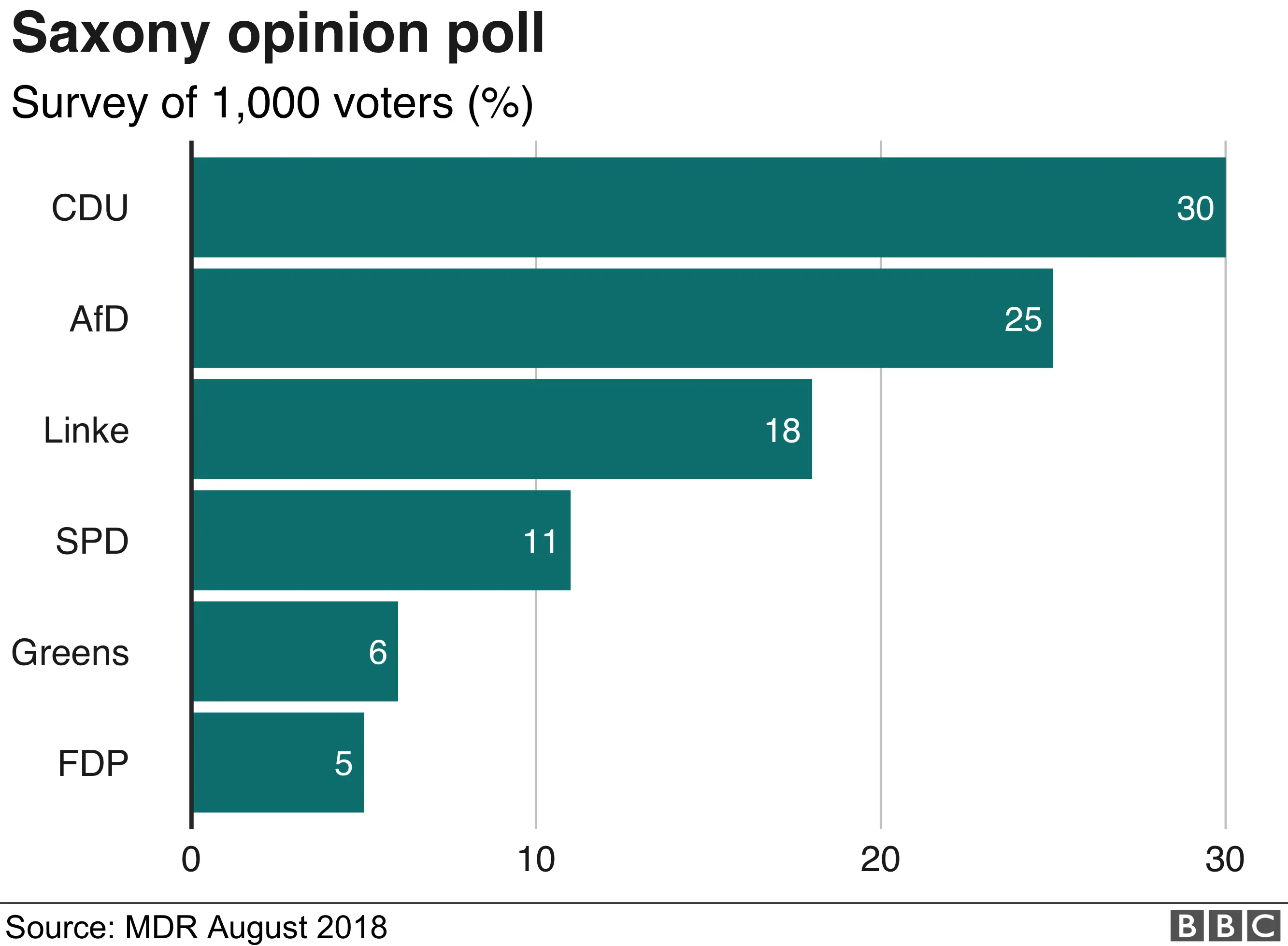

But it is a stronghold for the anti-migrant party which national polls suggest is also on its way to becoming the country's second largest party.

The pictures from Chemnitz - the rage, the sorrow, the violence - suggest a Germany aflame with resistance to migration.

There is much evidence to the contrary.

The number of people seeking asylum has fallen steeply and there are integration success stories - one in four new arrivals has a job.

A national poll recently found that Germans are now more concerned about health, pensions and climate policy.

But migration remains a highly charged political theme.

And, even as local politicians appeal for calm, Germany's establishment has yet to find a way to truly soothe the disquiet which roared into such violence at the weekend.