Turkey election: Erdogan win ushers in new presidential era

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan is taking on extensive new executive powers following his outright election victory in Sunday's poll.

Parliament has been weakened and the post of prime minister abolished, as measures approved in a controversial referendum last year take effect.

Defeated opposition candidate Muharrem Ince said Turkey was now entering a dangerous period of "one-man rule".

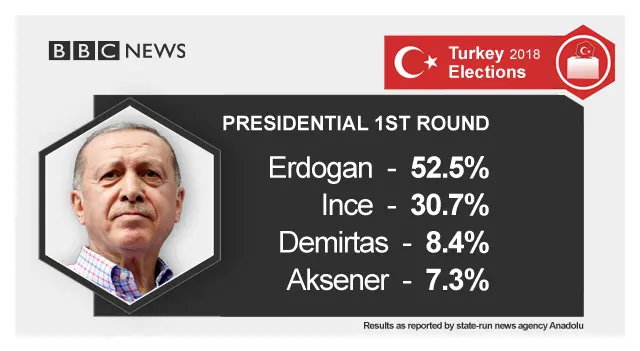

Mr Erdogan polled nearly 53% in the most fiercely fought election in years.

Mr Ince received just 31%, despite a lively campaign attracting huge crowds.

Mr Erdogan, 64, has presided over a strong economy and built up a solid support base. But he has also polarised opinion, cracking down on opponents and putting some 160,000 people in jail.

Congratulations have come in from around the world, though some Western leaders have been slow to react. Russian President Vladimir Putin talked of Mr Erdogan's "great political authority and mass support".

What do the new powers mean?

In his victory speech on Monday morning, Mr Erdogan vowed to bring in the new presidential system "rapidly".

The constitutional changes were endorsed in a tight referendum last year by 51% of voters.

They include giving the president new powers to:

- directly appoint top officials, including ministers and vice-presidents

- intervene in the country's legal system

- impose a state of emergency

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome critics argue that Turkey's new system lacks checks and balances.

Mr Erdogan says his increased authority will empower him to address Turkey's economic woes and defeat Kurdish rebels in the country's south-east.

Mr Erdogan was prime minister for 11 years before becoming president in 2014. Under the new constitution, he could stand for a third term when his second finishes in 2023, meaning he could potentially hold power until 2028.

'Progressive values are still here'

By Mark Lowen, BBC Turkey correspondent

Despite 90% of the media being pro-government and largely shunning the opposition, the president's posters and flags dwarfing any challenge on the streets, the election being held under a state of emergency curtailing protests, and critical journalists and academics being jailed or forced into exile, Mr Erdogan only got half of the country behind him.

"We are living through a fascist regime," opposition MP Selin Sayek Boke told the BBC. "But fascist regimes don't usually win elections with 53%, they win with 90%. So this shows that progressive values are still here and can rise up."

For now, though, this is Mr Erdogan's time. With his sweeping new powers, scrapping the post of prime minister and able to choose ministers and most senior judges, he becomes Turkey's most powerful leader since its founding father Ataturk.

He'll now hope to lead the country at least until 2023, 100 years since Ataturk's creation. And a dejected opposition will have to pick itself up and wonder again if, and how, he can be beaten.

How did the opposition react?

Mr Ince, from the Republican People's Party (CHP), said the election was unfair from its declaration to the announcement of the results.

"We have now fully adopted a regime of one-man rule," he told journalists after the vote.

EPA

EPABut he said he did not dispute the official results. The other four candidates on the ballot fell below 10% of the vote.

How was the election conducted?

Security was tight. Ahead of the vote, concerns had been raised about potential intimidation and electoral fraud.

Turnout was high at almost 87%, the state broadcaster reported.

Observers from the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) said that although the election had offered a genuine choice, Mr Erdogan and his party had enjoyed an advantage.

"Regrettably, contestants did not have equal opportunities to compete and to campaign," the group said, echoing concerns of rights activists.

It said the state of emergency in place since 2016 had caused limits "to freedom of expression and assembly" which affected other political parties.

The OSCE was also critical of the unequal media coverage given to candidates, in a country which monitoring groups say has become the world's biggest jailer of journalists.

In a statement, European Union officials echoed the OSCE's view that "conditions for campaigning were not equal". It also warned that the president's new powers had "far-reaching implications for Turkish democracy".

Mr Erdogan's spokesman, Ibrahim Kalin, told the BBC his country's election system was "very clear and transparent".

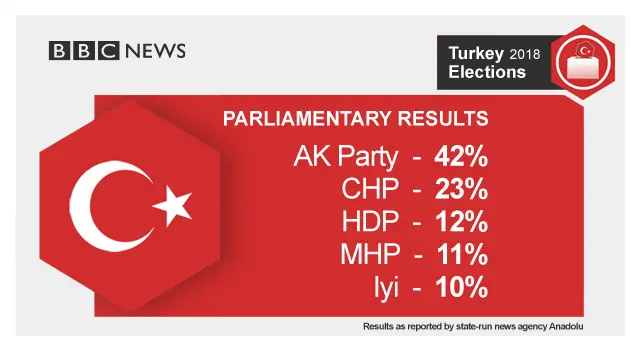

In separate parliamentary elections, the governing alliance led by Mr Erdogan's AK Party (AKP) secured a majority, with 53% and about 343 seats.

The opposition CHP and its allies won only 33% (190 seats). However, the pro-Kurdish HDP re-entered parliament with 67 seats.

AFP

AFPThe party's success comes despite the fact its presidential candidate Selahattin Demirtas is in a high-security prison on terror charges, which he denies.

The biggest issue for voters was the economy. Inflation stands at about 11%, though the economy has grown substantially in recent years.

The Turkish lira has suffered as Mr Erdogan has pressed the central bank not to raise interest rates and suggested before the poll that he might restrict its independence.

Terrorism was another key issue, as Turkey faces attacks from Kurdish militants and the jihadists of the Islamic State group.

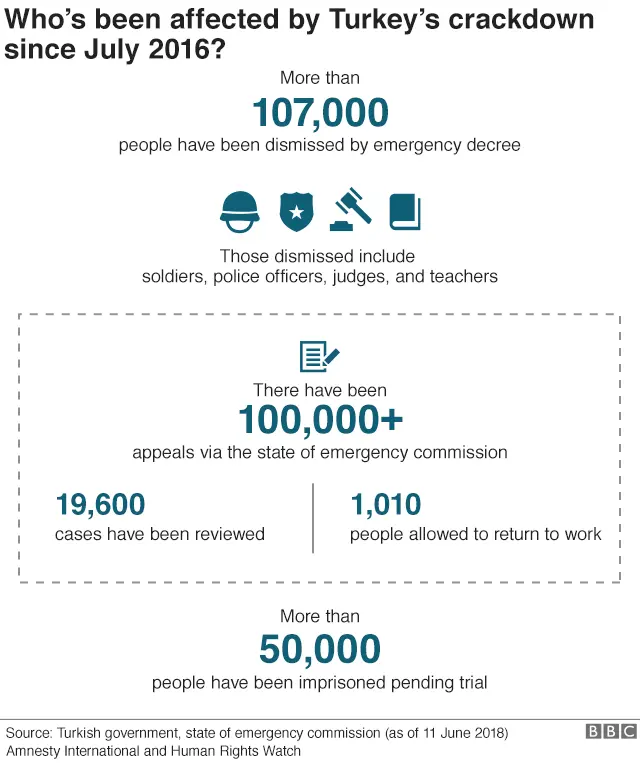

Turkey has been under a state of emergency since a failed coup in July 2016, with 107,000 public servants and soldiers dismissed from their jobs. More than 50,000 people have been imprisoned pending trial since the uprising.