Macedonia and Greece: Backlash over name deal

EPA

EPAMacedonia's president is refusing to sign an historic deal agreed with Greece to change his country's name, saying it violates the constitution.

"My position is final and I will not yield to any pressure, blackmail or threats," Gjorge Ivanov declared.

On Tuesday, Macedonia and Greece agreed to end a 27-year row by renaming the ex-Yugoslav state "The Republic of North Macedonia".

The goal was to distinguish it from an identically-named Greek province.

That mattered to Athens, which argued that by using the name Macedonia, the country was implying it had a claim to the Greek region.

So, is this a U-turn by Macedonia?

No - it's down to a disagreement between the president and Prime Minister Zoran Zaev, who struck the deal with his Greek counterpart Alexis Tsipras.

The dissent comes from President Ivanov, who is strongly connected to the nationalist VMRO-DPMNE party that was forced from power in 2017. He has the power to veto the deal - but not indefinitely.

The foreign ministers of Macedonia and Greece are expected to sign the accord this weekend. Macedonia's parliament will then vote on whether to approve it.

If it votes in favour, the president can refuse to sign it off - which would send it back to parliament for a second vote. If it passed again, Mr Ivanov would be obliged to approve the legislation.

EPA

EPAMr Zaev's government needs a two-thirds majority to get the deal through parliament. However, it can't secure that without the opposition VMRO-DPMNE party, which won't support it.

The president is also refusing to be swayed by possible future membership of the EU and Nato.

Greece has historically blocked Macedonia's bid to join these blocs over the name row - a stance that should now end.

But Mr Ivanov says a shot at membership would not justify signing a "bad agreement".

Storms but no surprises from Macedonia's president

By Guy Delauney, BBC Balkans correspondent

President Gjorge Ivanov's opposition was always to be expected - and he has not disappointed. Reports suggest that he stormed out of a meeting with Prime Minister Zoran Zaev after just three minutes.

This is unsurprising, considering he was nominated to run for president by the nationalist VMRO-DPMNE party which was forced from power last year.

Reuters

ReutersMr Zaev will not be losing any sleep over the president's outburst. He is fully aware that Mr Ivanov can only use his veto once - and has no power to block a referendum.

A bigger conundrum is how to win over the opposition. At least some VMRO-DPMNE MPs will be needed to gain a two-thirds majority in a parliamentary vote.

In Greece, Alexis Tsipras faces similar, also predictable, problems - especially as he lacks the support of the junior partner in his governing coalition.

What's the reaction in Greece?

Prime Minister Tsipras has also faced heavy criticism from political opponents.

Greece's main opposition party, New Democracy, has threatened to submit a motion of no-confidence in the government.

Its leader Kyriakos Mitsotakis called the deal "deeply problematic", and said most Greeks opposed it.

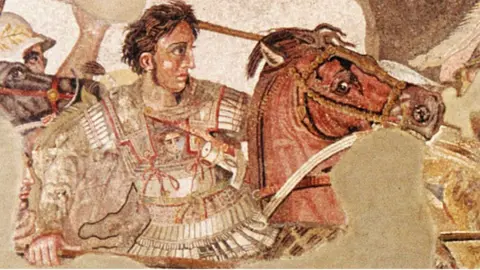

Critics have accused Mr Tsipras of surrendering part of Greece's cultural legacy, insisting that the title Macedonia belongs to Greek culture and heritage because it was the name of the ancient Hellenistic kingdom ruled by Alexander the Great.

Under the deal, Greece's northern neighbour can define its language and ethnicity as "Macedonian".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesConservative newspaper Eleftheros Typos branded the deal "the surrender of the Macedonian identity and language".

Mr Tsipras has firmly rejected that analysis. In a TV address on Tuesday, he said Greece was becoming "a leading power in the Balkans" and "a pillar of stability in a deeply wounded region".

What needs to happen for the name change to go through?

The aim is to get Macedonia's parliament to back an agreement before EU leaders meet for a summit on 28 June. Greece will then send a letter to the EU withdrawing its objection to accession talks, and a letter to Nato too.

That would be followed by a Macedonian referendum in September or October.

If voters there back the deal, their government would have to change the constitution, a key Greek demand.

The deal will finally have to be ratified by the Greek parliament - which looks unlikely to be straightforward.