Portugal's wildfire that broke a community

Getty Images

Getty Images"It's been like this every day and it's always about the same thing. The fire."

The phone rings incessantly at Sílvia Bento's desk in the Pedrógão Grande Mayor's office.

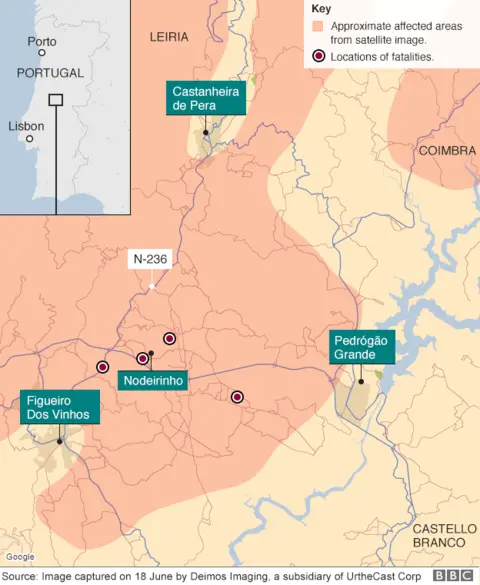

It was on 17 June last year that a wildfire raged through this part of central Portugal, devastating an area four times the size of Lisbon, destroying hundreds of homes and killing 66 people.

Many victims were trapped in their homes or in their cars as they tried to escape. It was the deadliest fire in Portuguese history.

"It's like it was yesterday," says Sílvia Bento.

A year on, the ferocity and the scope of this tragedy are marked by thousands of acres of black and brown mountains and valleys stretching as far as the horizon.

The constant buzz of chainsaws suggests work on reviving the area has begun. But a lack of funding, a lack of people and the sheer shock of the disaster mean it will take some time for this part of central Portugal to recover.

Toll of the Pedrógão Grande fire

- 66 people killed, many of them trapped in vehicles on the N-236 road

- 253 injured

- 485 houses destroyed

- 53,000 hectares of land burned, including 20,000 hectares of forest

- 2,018 farmers affected at a cost of €21m (£19m; $25m)

- 49 companies affected at a cost of €31m

"Even after what happened, the locals look around and everything reminds them of what happened. Even if they want to avoid that reality, they can't," says Ana Santos, an expert in grief therapy at the PIN psychology centre.

She says there are several cases of mourning and severe trauma in the area surrounding the councils of Pedrógão Grande, Castanheira de Pêra and Figueiró dos Vinhos.

Ana Margarida Teixeira, a local psychologist working on the ground since day one, says cases of post-traumatic stress disorder are rare but that almost every week new patients sign in at the public health clinic where she works.

"The population has been very resilient. They're looking at what happened as an opportunity for growth and there is less stigma regarding asking for help than I thought," she says.

Among the survivors who has sought help is Lídia Antunes, whose family survived the disaster, but only just.

On the day of the fire, they fled their house in three different cars. They soon lost track of each other and became cut off on flame-ridden forest roads.

"I was convinced I was going to die. I was speeding through flames and it was so hot, I though if I tried to U-turn the car would melt," she says. "At some point I got lost and got hit by another car but I just kept speeding. I knew that as soon as the car stopped I would die."

She drove on and ended up saving a couple pleading for help.

"I told them to get in quickly, but the back doors of the car had melted, so the two of them had to get in through the passenger's window.

"An elderly man who was with them couldn't get in and decided to stay behind. To this day I have no idea if he survived," she says.

Lídia is on medication and still has sleepless nights.

"Every day I think why did I leave? But then I think I wouldn't have saved those two people if I'd stayed at home," she says. "That makes it a bit easier."

Castanheira de Pêra, is a town of 3,000 people where everyone has been touched by the fire. And everyone has a story.

Mayor Alda Correia still finds it hard to talk about. "We can repair the physical losses," she says, holding back tears. "But the emotional part, the blackened souls, those I can't mend."

So far 157 of the 261 destroyed houses here have been rebuilt, according to the Ministry of Planning and Infrastructure.

Ms Correia says much has been done so far, but the administration is struggling with lack of funding and depopulation.

For the Tomás family, who have operated the biggest wood company in the area for the past 40 years, the fire has proved a threat to their livelihood.

Their lumber plant was destroyed at a cost of more than £4m in damages. The company managed to rebuild and keep all 50 employees' jobs, but it's now struggling with the falling wood prices and lack of raw material.

Sandra Tomás, the company's manager, believes they will be forced to move to Spain to look for raw material in two years' time. "Pines take 40 years to fully grow, what are we and our employees supposed to do until then? Wait?"

"Look at all this wood. it's worthless," says her husband Nuno, who runs the lumber business.

Around him lie countless piles of pine and eucalyptus logs.

"There's so much of it that the market is saturated". The constant echo of chainsaws is a measure of the race against the clock to save the tarnished wood before it rots.

A future for Castanheira

Alda Correia's biggest priority now is to bring in investment so that people stay in Castanheira de Pêra.

She wants to put the region on the map "as a getaway from the tourist frenzy sweeping the country", to boost the local economy and restore its image of natural beauty.

For grief therapist Ana Santos, the idea of an image tarnished by fire is not uncommon. "Finding a new goal is important to restore their identity and meaning to their lives," she says.

Young, silver-green eucalyptus trees are beginning to grow in this charred landscape.

Newly built houses painted in white, yellow and pink are bringing colour back to the town.

A tank in which a whole family took refuge during the fire is again feeding the local cattle.

And the N-236 road where dozens of people died has a new layer of asphalt and signs where people can leave flowers.

"Life is getting back to normal," says Silvia Bento at the mayor's office. "People don't talk about it every day any more.

"But it's in our minds every day. Definitely, we will never forget".