Sweden's deadly problem with hand grenades

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA stark rise in incidents involving hand grenade explosions has become emblematic of the wider rise in violent crime in Swedish cities, report James Clayton and Caitlin Hanrahan for BBC Newsnight.

Daniel Cuevas Zuniga was cycling home from a night shift in southern Stockholm in January when he stopped to pick up an object on the path.

Police believe the 63 year old, who worked at an elderly people's home, thought the device was a toy.

But it was a hand grenade, which exploded as he touched it and killed him almost immediately.

His wife, Wanna, was riding ahead of him near Varby railway station. She was knocked to the ground by the blast.

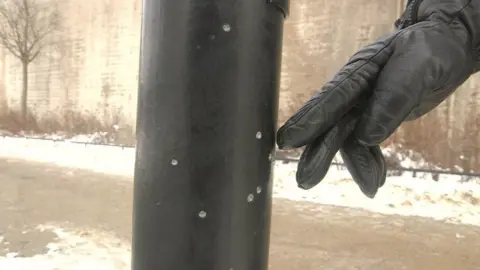

Shrapnel marks can still be seen on a nearby lamppost.

"How could a hand grenade be on the bike path?" Wanna said later in an interview with local media.

"My view on Sweden has changed. I really wonder how such a thing could happen... I am completely traumatised."

The number of explosions caused by hand grenades has increased in Sweden in recent years. There were fewer than five in 2014 but at least 20 in 2017, and a further 39 grenades were seized by police.

The devices are easily obtained, says Reine Bergland of Stockholm police. They can be bought from gangs for just a couple of hundred Swedish kroner (about £20).

"Sometimes when they buy weapons they get grenades as part of the deal. They throw in a couple of hand grenades, so to speak."

The rise in possession of hand grenades - mainly unused stock from the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s - has come to symbolise Sweden's heated debate about violent crime as it heads towards an election in September.

The rate of violent crime in the suburbs of Sweden's big cities has worsened in recent years, in what officials blame on rising gang-related crime.

There were 306 shootings last year, which left 41 people dead. In 2011, there were 17 fatalities.

The violence has turned some parts of Stockholm into "no-go zones" for paramedics, says Henrik Johansson, former head of Sweden's paramedics union.

"People who live in these areas are very scared to call the police or get help from ambulances. They are scared about consequences for them and their families."

Police have acknowledged 60 or so "vulnerable areas" but reject the description of "no-go zones", a highly loaded term in Sweden.

After all, violent crime in Sweden and who is to blame for it has become an ideological battlefield.

In February 2017 US President Donald Trump controversially linked the problem to the influx of migrants to Sweden.

"Sweden. They took in large numbers. They're having problems like they never thought possible," he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesA self-proclaimed humanitarian superpower, Sweden took in the highest number of asylum seekers per capita during the migrant crisis of 2015. Many were refugees fleeing war and abuses in Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan and Eritrea.

There is very little evidence that the migrants are to blame for a rise in violent crime. But Sweden - so often the place that countries have looked to follow on social policy - has not been so successful at integrating migrants over the past 20 years.

A short drive from the centre of Stockholm, the suburb of Rinkeby is an island of breeze-block flats and estates that even the snow struggles to beautify.

A riot last year gave the impression of a Swedish dystopia in this neighbourhood made up mainly of immigrants and their children.

But some people here are angry at the way their neighbourhoods have been stigmatised, particularly by the country's right wing, and say they seem to be drifting away from mainstream Sweden.

Hashim and Amin, both of Somali origin, helped set up a local anti-violence group. They accept that some types of violent crime are increasing but accuse the government of failing to invest in these areas.

"Instead of finding a solution for the complex problems you call them a 'no-go zone'. It's just labelling it, making it easy for police to decide for people, instead of including people in the decisions," said Amin.

Hashim added: "I don't think Swedish society is very open for immigrants, there's a lot of xenophobia."

Sweden's government denies it is immigrants who are causing the rise in crime.

"The people who are causing problems for us today, the vast majority of them are born in Sweden, and that's not a notion of migration. That's an issue of integration and an issue of social inclusion," said Justice Minister Morgan Johansson, a centre-left Social Democrat.

"One per cent of the population in our Swedish prisons are Syrians. One percent are from Afghanistan."

The government insists it is tough on crime and tackling its causes.

But as many people in Sweden become increasingly concerned about violence, it may be harder to convince them that accepting large numbers of migrants will not lead to further social problems down the line.

The justice minister accepts that violent crime will be an issue in September's election but would rather voters focus on Sweden's strong economic growth.

And the far right here are looking to emulate the successes of other anti-immigration parties elsewhere in Europe.