What does the expulsion mean for Russia’s spies?

AFP/Getty Images

AFP/Getty ImagesOn 24 September, 1971 there was a party in the headquarters of MI5. The safe that was used to stash bottles of drink was opened up and a bottle or two pulled out for a toast. The reason was "Operation Foot" - the expulsion from the UK of 105 Soviet officials linked to espionage.

Moscow's spies had been running riot in Britain through much of the 1960s. There were so many that MI5 was struggling to keep tabs on their movements. That expulsion was a blow that the KGB, the Soviet Union's intelligence service, never quite recovered from.

In that instance, while allies congratulated Britain they did not follow through in the same way. This time it has been different. But will the impact be as great?

The avowed goal this time is both to send a message, and to have a substantial impact on the ability of Russia's intelligence services to collect secrets and carry out operations abroad.

As in the Cold War, intelligence officers at embassies are used to recruit and run agents who supply classified material to Moscow. They come from the GRU - military intelligence - and the SVR, the foreign intelligence successor to the KGB. Relationships with any agents they are running may be interrupted, perhaps fatally.

More than in the Cold War, these (and other colleagues from Russia's domestic security service, the FSB) may also have a mission in gathering intelligence on exiles as well. Some will have been involved in "active measures" - covert activities which can include the spreading of propaganda and political influence. These activities may be handicapped.

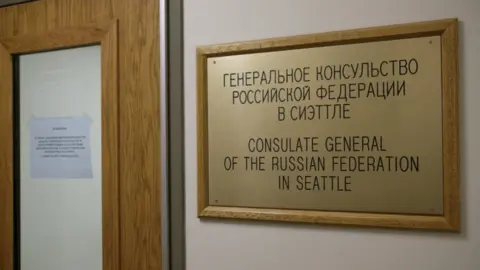

As well as the sheer volume of suspected spies expelled from multiple countries, one of the most significant moves may be the closure of the Russian consulate in Seattle, said to be because of its proximity to a submarine base and to the aircraft manufacturer Boeing, which has a large chunk of its global workforce in the area.

EPA

EPAThese consulates can play a significant role in espionage since they act not only as a base for intelligence officers, but also potentially as a home to communications interception equipment.

The impact may not be quite the same as the Cold War though. One reason is cyberspace. In the past, the only way for Moscow to gather intelligence or steal secrets was through human intelligence or intercepting communications, but now it can reach out using its effective cyber-operators to steal secrets and gather non-classified material remotely.

This is not a total substitute for the human intelligence provided by agents - and the two often combine in practice - but it does offer a new avenue. Cyberspace may also offer a route for Moscow to strike back against the countries that have expelled its officers - perhaps not just by stealing secrets but by carrying out "active measures", "influence operations" and even sabotage online in a way which was not possible in the past, but is now.

Everyone knows Russia will respond with its own expulsions. But the truth is that most countries, even the US, are thought to have fewer spies in Russia than Russia does in their territories. Russia will also send out new spies to replace the old.

The hope will be that the scale of these expulsions - and the international nature of them - will deter Russia from using its spies abroad to carry out acts like those it is suspected of being involved with in Salisbury.

The disruption will also allow the counter-espionage, spy-hunting services, like MI5 in the UK and the FBI, to gather breath and re-focus their efforts once again.

And so, perhaps there might be another bottle pulled from a safe for a celebration after the latest expulsions.