The Czechoslovak spy who met Jeremy Corbyn

BBC

BBCMuch of the news in the UK this week has been driven by allegations by a former Czechoslovak spy that the opposition Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was a paid informer for the country's communist era secret police, the StB.

Mr Corbyn emphatically denies the claims. Indeed all the evidence suggests he was never anything more than a person of interest to the StB. But as Rob Cameron reports from Prague, while the Cold War is over, a few sheaves of yellowing paper still have the power to throw lives into turmoil.

As I sat at my computer, poring over secret police files, I felt a sudden tug of nostalgia. The files were digital copies of reports written by StB officer Jan Sarkocy, sent to Britain in 1986 under diplomatic cover. When he met first Jeremy Corbyn, in November of that year, his business card read "Jan Dymic, Third Secretary to the Czechoslovak Embassy in London".

They were fascinating documents, cryptic and - for me - strangely evocative. Especially the references to North London landmarks I knew well, such as Seven Sisters Road, where the Labour MP for Islington had an office.

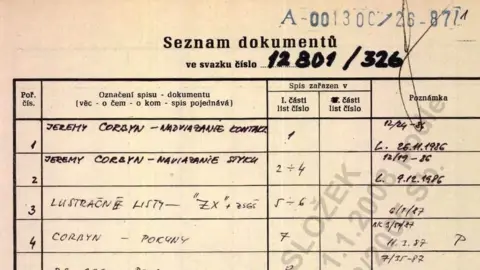

Security Service Archive

Security Service ArchiveBut my task was not to dredge up my own memories of Labour politics while the party was in opposition in the 1980s. Rather it was to examine the six documents in dossier number 12801/subsection 326, codename "COB", for traces of anything incriminating. And believe me, I couldn't find them.

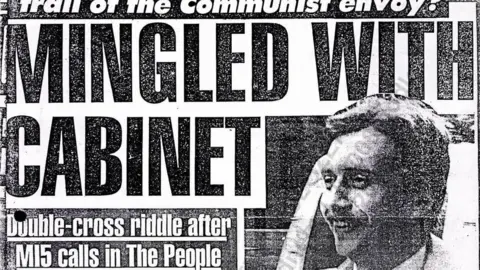

Nothing in Agent Dymic's descriptions of three meetings with the Labour MP - two in the House of Commons, one on Seven Sisters Road - suggest the StB ever regarded him as anything other than a potential source. A young leftist with good contacts in the peace movement. An internationalist with a Chilean wife who kept dogs and goldfish. The only document he appears to have passed on to Agent Dymic was a photocopy of an article in the Sunday People about a bungled MI5 raid on the East German Embassy. And each meticulous report ended with a little note of expenses incurred; parking, two pounds; underground ticket, one pound. Signed: Jan Dymic.

Security Service Archive

Security Service ArchiveFor clarity I spent a morning with the woman who is now the custodian of millions of documents still marked "TOP SECRET": the Director of the Czech Security Services Archive. For research purposes these dossiers - once jealously guarded by the Communist-era secret police and intelligence services - are now freely available to anyone; all you have to do is ask for them.

The director had also given me Dymic's own personnel file. But his Slovak was littered with arcane abbreviations and jargon, and I was having trouble understanding them. "COB" was Jeremy Corbyn's codename, that much was obvious. Nothing sinister in that, she told me; the StB used them for everyone, including people they were interested in cultivating.

OK, but what were "GREENHOUSE I" and "GREENHOUSE II" - mentioned repeatedly in the files? The Czechoslovaks seemed obsessed with trying to penetrate these targets, and many of Dymic's approaches to British politicians - Jeremy Corbyn among them - were initiated with the aim of gaining access to them.

"GREENHOUSE…" the director frowned, peering at the screen. "I'm sorry...." she admitted, after a few minutes. "I've really got no idea."

Two days later, speeding down the motorway to Slovakia, I made a mental note to ask Agent Dymic - now just Jan Sarkocy - what this "GREENHOUSE" was. I had mixed feelings about this meeting, secured after many emails and texts. At home, the StB were the praetorian guard of Czechoslovak communism, responsible for hounding dissidents, torturing priests, and spying on a cowed population. Today, the epithet "estebak" - an StB officer - is still a term of abuse. They also had several high-profile successes abroad; recruiting two Labour MPs from the UK in the 1950s and 60s. Their rivals in military intelligence even recruited a Conservative one.

After a huddle outside his house with Slovak reporters - where he made his explosive claims - Sarkocy had gone to ground, and was no longer talking. But finally, he relented, and so I now found myself outside his home in the village of Limbach, about half an hour north of Bratislava.

A thick layer of snow lay on the ground as we waited for him to answer the door. Lines from John Le Carre novels filled my head. "It is cold in Limbach at this time of the year," I said in an exaggerated East European accent, to ease the tension. My Czech colleague - there to film the interview - laughed.

In the end Jan Sarkocy was garrulous and friendly, still regarding his brief tenure in London with great affection. Most of what he told me, about an array of people and institutions, was so libellous - not to mention confusing - that I cannot even begin to repeat it here. But oddly not even he could remember what GREENHOUSE I and GREENHOUSE II were.

The answer finally came from a BBC colleague. "I've made some calls," he wrote. "The main effort of the StB abroad, as directed by their Russian masters, was to penetrate the UK's intelligence agencies. So GREENHOUSE I was probably Century House, the former headquarters of the SIS, more commonly known as MI6." Ah. And GREENHOUSE II was, I suppose, the headquarters of MI5.

The GREENHOUSE mystery solved, and the Corbyn frenzy dying down in London, I boarded a train back to Prague. As the 12:10 from Bratislava sped through the frozen fields, my head still spinning, I did what any journalist does at the end of a story: my expenses. Parking; two euros. Tram ticket: one. I suddenly had an image of Jan Sarkocy doing his in London 30 years ago.

A different job. A different era. But some things, I suppose, never change.