Turkey brain drain: Crackdown pushes intellectuals out

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBulent Somay didn't choose to leave - he feels Turkey pushed him out.

The 61-year-old professor packed his life into a dozen boxes, bade farewell to his students at Istanbul's Bilgi University and moved to a new teaching position in Brussels, where he believes he's no longer at risk.

He is just one of a growing brain drain of those opposed to Turkey's direction.

"We're not even feeling safe during lectures anymore", he said, clearing the shelves in his Istanbul apartment.

"We have to watch what we're saying. Some students record you and you see it on pro-government media - that you're insulting the president. You write something and you start getting threats and insults."

He stacked another box with his prized academic books, deciding which of his 2,000 he would take.

"I used to have a very healthy relationship with my religious students," he recalled. "But now they feel they're the elite and we're the pariah. Years ago, they were trying to get power. Now they have it, they're questioning our right to share it."

Bulent Somay is one of 1,128 academics who signed a petition in 2016 calling on Turkey's government to cease armed conflict with Kurdish militants.

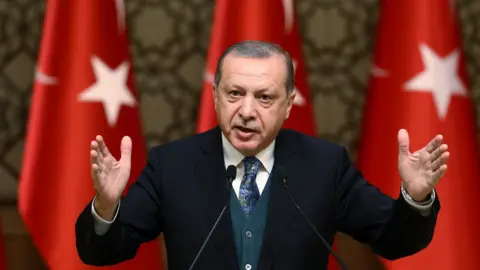

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan accused them of treason. A pro-government mafia boss warned he'd "spill their blood and bathe in it". The scholars' universities duly expelled them.

Those who could are leaving Turkey. Others are on trial for "terrorism propaganda".

Since the failed coup of July 2016, in which more than 260 people were killed, a wave of emigration from Turkey has quickened. The post-coup clampdown has seen 60,000 people arrested and 150,000 suspended or dismissed.

Not only academics are leaving

As well as intellectuals, there's a broader exodus from the country's secular side, as the grip of religious nationalism grows tighter. There are no official statistics on the migration flow. But through our research, we collected some examples.

Since the Kurdish petition was signed in 2016, 698 Turkish academics have applied to the New York-based organisation Scholars at Risk to be moved abroad to a safe position.

Reuters

ReutersIn the past five years, 17,000 Turkish nationals came to Britain, UK Home Office figures showed. The German Statistics Office says around 7,000 Turks have moved to Germany during that period and about 5,000 have moved to France, according to the French Interior Ministry.

Others are looking for an alternative way out.

Among them are more than 4,500 Turks of Jewish descent, who have applied to Spain and Portugal for nationality - a considerable proportion of Turkey's small Jewish population.

The two countries are offering nationality to atone for the expulsion of Iberian Jews during the 15th Century Inquisition, when the Ottoman Empire absorbed a large number. Many more non-Jewish Turks are also trying to move there.

No Jewish applicant whom we spoke to was willing to go on the record. Few of those trying to leave Turkey at all, or indeed critics of the government, are now ready to give interviews - a sign of the climate of fear that's engulfed the country.

We spoke to one man moving his whole family to Spain, on condition we withheld his name. "It breaks my heart that I'm leaving - but I can't breathe here anymore," he said.

"My thoughts are not wanted; the way I want to live is not wanted. We now have to choose a side. If it's not the right side, your business won't grow or you can't express your feelings - otherwise you'll have trouble. You need to be Muslim, Sunni and pro-government."

I asked if it was his Jewishness or his criticism of the government that's made him feel a target. "Both", he replied. "When I say I'm Jewish, I've heard many times: 'you describe yourself as a Jew - not a Turk?'"

Buying your way in

More people still are moving to Greece. Turks now rank third in buying property there to get residency: in the past four years, the Greek government said 430 Turkish nationals have been granted a so-called Golden Visa by purchasing property of €250,000 (£221,000; $296,000) or more.

The price is €350,000 in Portugal or Spain, which grants nationality in return - another reason behind the surge in Turkish applicants there.

Selcan Turk, a Turkish estate agent in Athens, took me around an apartment with a view of the Acropolis that she recently sold to a Turkish family. Last year, she showed three properties a month to Turks. Now it's three a week.

"People don't feel safe in their country anymore regarding human rights, democracy and justice", she said. "They feel here that there is real democracy and freedom".

That is what those leaving believe Turkey now lacks: even the aim of striving for the Western-style democracy it once craved. Perhaps allowing the critics to go handily removes the checks and balances on a government many feel is increasingly authoritarian.

AFP

AFPTurkey has seen migration waves in past decades: hundreds of thousands moved to Germany in the 1960s as so-called guest workers, filling the post-war need for cheap labour. Some of them returned as Turkey's economy boomed, feeling at home under Mr Erdogan's pious government.

But it's the other side of the population now leaving in ever-greater numbers: the liberals, the intellectuals and the well-to-do.

And in years to come, Turkey will count the cost of losing so many.