Catalonia snap election: What to know as voters go to polls

Spain's struggle with Catalan separatism, which made world headlines in October, is taking a new turn with a knife-edge vote.

People in the semi-autonomous region are going to the polls on Thursday. They will decide whether to support politicians who want to build a new, independent country, or unionists who want to stay in Spain.

The snap election was called by the Madrid government as part of measures to control the north-eastern region after leaders there declared independence.

The results of the vote could determine Catalonia's direction for years to come.

Why is there an election in Catalonia?

Years of separatist pressure boiled over on 1 October when, defying Spanish courts and riot police, the Catalan authorities held an illegal referendum.

According to the organisers, 90% of voters were in favour of independence. Yet fewer than half the region's electorate took part, so nobody can say for sure how much real support there was for a split.

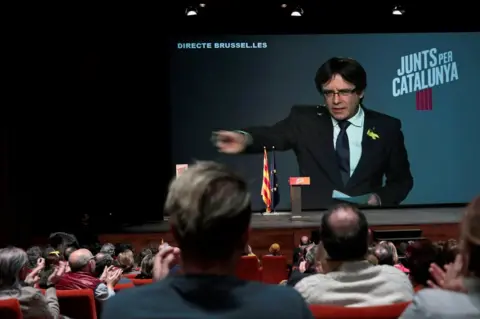

Catalonia's president at the time, Carles Puigdemont, decided it was enough to declare independence from Spain.

Spain's government under Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy hit back - sacking the regional government, dissolving the regional parliament and calling the early election.

It is gambling on voter disenchantment with separatism, and hoping for a result that anchors the wealthy region firmly back with Spain. But it must also contend with anger over Madrid's crackdown during the crisis.

"Independence is over, the so-called procés [independence movement] is finished," says Manuel Arias Maldonado, political science professor at Málaga University.

However for Oriol Bartomeus, political science professor at the Autonomous University of Barcelona, this is "Referendum 4.0" - following on from a mock referendum in 2014, the 2015 regional election, and October's banned vote.

Why are separatists taking part?

When the Spanish government rolled back the region's extensive autonomous powers, it was accused by Catalans of crushing democracy.

Former ministers and the parliamentary speaker were jailed while they were investigated on suspicion of rebellion, while Mr Puigdemont fled into self-imposed exile in Belgium.

So it may come as a surprise that the separatists are either willing or able to take part.

Yet after initial dismay, they took up Madrid's challenge at the ballot box, under slogans like "Puigdemont our president" and "Democracy always wins".

SomRepublicans

SomRepublicansFor pro-independence voter Josep Jaume Rey: "It's a second round of the referendum we weren't allowed to legally hold."

Who will win the election?

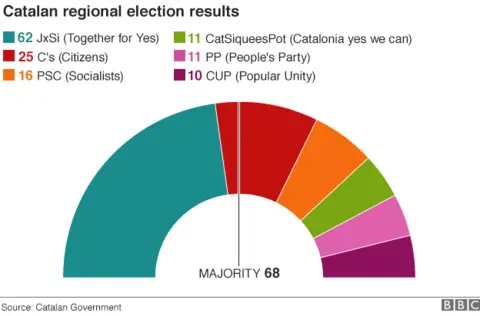

The main question is whether the pro-independence parties will manage to secure a majority in the Catalan parliament. If they do, the drive for independence is unlikely to die down.

At the 2015 election, most of the separatist parties joined forces and stood under the name Together for Yes - urging "Yes" to the holding of a referendum and "Yes" to independence.

The alliance consisted of Mr Puigdemont's centre-right Democratic Convergence of Catalonia, the social democratic Republican Left of Catalonia (ERC), and two smaller parties.

With the help of a fifth party, the radical anti-EU Popular Unity Candidacy (CUP), they managed to get enough support in parliament to call the ill-fated October referendum.

In this election, by contrast, the separatist camp is split:

- Under its imprisoned leader Oriol Junqueras, the ERC opted out of a new alliance with Mr Puigdemont

- Mr Puigdemont's party, relaunched last year as the Catalan European Democratic Party, allied itself instead with independent candidates to stand as Together for Catalonia (JxC)

- The CUP is standing on its own again

EPA

EPAWhy are the separatists divided?

Mr Puigdemont's decision to go into exile was justified by his supporters as the only way to keep alive their new independent republic - but it caused some ill-feeling back in Catalonia.

Prof Arias Maldonado sees a clear feud between the two big parties: "Apparently, Puigdemont has become a liability since he has announced that he will come to govern should his bloc win - something the ERC does not like to hear."

EPA

EPAMarc Sanjaume, professor of political sciences at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, says the split between the parties allows pro-independence voters who are angry with Mr Puigdemont to punish him while still supporting other secessionists.

What about the unionist parties?

The woman placed in temporary control of Catalonia by Prime Minister Rajoy when he sacked its leaders, says Spain's ruling, centre-right Popular Party (PP) has "decapitated" the pro-independence parties.

Soraya Sáenz de Santamaría claims only the PP can "continue liquidating the independence movement".

Her remarks drew a fresh outcry that the Spanish government was only prosecuting separatist leaders for political gain.

Allow X content?

Despite its zeal, or maybe because of it, the PP has not benefited in opinion polls from any pro-unionist backlash in Catalonia - quite the reverse.

Instead, both the liberal Citizens (Cs) - which ate into the PP share of the vote at the Spanish general elections of 2015 and 2016 - and the Socialists (PSC) have seen their support rise significantly.

Reuters

ReutersTaken together, the three unionist parties look set to fall well short of an overall majority - although Cs, under its energetic young leader Inés Arrimadas, could well end up the biggest party in parliament.

"If that happens, it would in itself be a political revolution in Catalonia and, by extension, in the rest of Spain," says Prof Arias Maldonado.

Is there any middle ground?

EPA

EPAIn Common We Can is an alliance of anti-capitalist and ecological parties endorsed by Barcelona's charismatic Mayor Ada Colau and led by Xavier Domenech.

It steers a middle course, calling for greater autonomy for Catalonia inside Spain and reforms that would enable a legal referendum on independence.

It looks on course to win fewer seats than its anti-capitalist predecessor in 2015 but may still emerge as king-maker in coalition talks.

Is this a free and fair vote?

Catalan voter Juli Morató says separatists fear "the manipulation of results".

Some errors appear to have been made in voter registration - but nothing, it seems, on a scale to justify suspicions of electoral fraud.

Calls for international observers to be admitted were rejected by the Spanish Central Electoral Commission as "inappropriate".

The campaign has not been free of censorship, however.

The authorities drew ridicule by banning the display in Barcelona of yellow ribbons, which are used to show solidarity with imprisoned Catalans.

Meanwhile, separatist politicians such as Mr Junqueras have been forced to run for election from prison. It is unclear whether Spain's courts will drop the charges against them - or against Mr Puigdemont - if they win.

"It has been a very strange campaign, more polarised than ever," says Prof Bartomeus. "The media have taken sides, even the public broadcasters. So fairness is low."