What now for Bosnia victims as Hague tribunal closes?

BBC

BBCAs the trial of General Ratko Mladic, overall commander of Bosnian Serb forces during the war of 1992-1995 comes to a close, the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia will effectively shut up shop.

But questions will remain about the fate of hundreds of others accused of violating the laws of war. Bosnia Herzegovina will continue to try people in its courts, but in that republic the question of going on with prosecutions divides opinion.

During the 24 years of its work the Tribunal indicted more than 160 people. They ranged from guards at the infamous Omarska camp, where non-Serbs were held in appalling conditions in 1992, to the architects of the assault on Srebrenica three years later, where more than 8,000 Muslim men were murdered.

When Mevludin Oric goes back to eastern Bosnia he sometimes spots men who he last saw in 1995 executing hundred of his kin from Srebrenica. "They are walking, laughing in my face," says Mevludin, "and saying 'I am the one who killed Muslims, Turks' and they are walking free".

Serge Ligtenberg

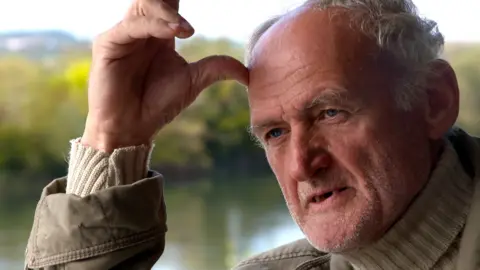

Serge LigtenbergI first met Mevludin in 1996, a few months after he had played dead in order to survive the machine-gunning of hundreds of prisoners by Serb troops. He gave evidence in three trials in The Hague.

Today his features have aged even more than you would expect over that passage of time and it is quite clear that Mevludin has never been able to put those terrible events behind him.

He does not see the issue of war crimes even-handedly either. His cousin, Nasser Oric, was a well known commander of Muslim forces in Srebrenica who himself stood trial in the Hague, accused of murdering Serb prisoners.

He was acquitted, but a subsequent prosecution was launched in a Bosnian court last year. When it was thrown out the day after our filming, Mevludin was jubilant.

"Every people, Serbs, Muslim, Croats, consider those indicted from their own people as not guilty, but they consider only 'the others' guilty," says former Bosnian Serb parliament speaker Momcilo Krajisnik, noting "there is a lot of subjectivity."

Mr Krajisnik served 13 years (on remand and following sentence in the Hague) in various jails including Belmarsh and Newcastle in the UK.

While he pointed out that the speakers of the Croat and Muslim assemblies had not been charged with similar crimes of responsibility for what happened, Mr Krajisnik accepted more generally, when we met, that he had done his time and it was pointless calling it an injustice.

Instead he pointed to the sectarian prism through which people still see the war crimes process and called for reconciliation between the republic's three main peoples.

The question now is whether trying to forge the country's future is helped or hindered by further trials. Many cannot accept that they should end.

Mia Karamehic, who was seven years old when she was wounded during the siege of Sarajevo, told me that nobody has ever been charged for firing the shell that killed 20 people in her street. She believes it is necessary to continue with the trials but at the same time blames politicians from all communities for exploiting the war.

"Every party that comes to power," she believes, "figures out the magical recipe for winning yet another election, which is nationalism and hostility".

Mia is expecting a baby now. She and her partner regard the political situation as hopeless and she says she may leave if the right academic or employment opportunity opens up elsewhere.

For older victims there are a variety of reasons for staying put.

Nusreta Sivac was working as a judge in the north-western Bosnian town of Prijedor when the war broke out. She was fired and shortly afterwards sent to Omarska camp along with around 6000 non-Serb male and 36 other female detainees.

She saw unspeakable horrors there, "mass killings, torture, harassment, starvation, [and] beatings". She was also raped.

At times Nusreta wished she was dead but, "then I would say to myself one day if I survive this, hopefully I will be able to bear witness to this maybe something good would come out of it".

She not only gave evidence at the trial of camp guards in The Hague but became one of those Muslims who returned to Prijedor after the war, refusing to accept the "ethnic cleansing" that had taken place there in 1992.

Filming with her in the streets and at a café opened by another returnee, it was quite clear that her decision to live her life in Prijedor (when many survivors or Omarska and other camps chose asylum offers abroad) demonstrated defiance of a very high order. And there is nothing simple about it.

For during the decades that have passed, some of those who brutalized the Omarska inmates have done their time and come home. Nusreta told us she had seen three of them in the streets. One had tried to engage her in conversation, trying to show there were no hard feelings.

Remarkably, these ex-guards also sometimes don the mantle of victim. We spoke to Miroslav Kvocka, convicted in 2001. He rejected the legal concept of "joint enterprise" under which the court had found him guilty, and insisted to us, as he had in The Hague, that he had saved his Muslim wife's brothers, "from getting their throats slit" in Omarska.

Returning to Prijedor there was no question of Miroslav resuming work as a policeman, instead he has taken labouring jobs, telling us, "nobody wants to employ a war criminal." Drawing deeply on a cigarette, he seems as hollowed out by his experiences as Mevludin, yet one is convict, the other victim.

While Nusreta Sivac is generally positive about the work of the international tribunal, believing those cases could never have been tried in Bosnia, she is critical of plea bargains struck there, and thinks sentences were too short.

She acknowledges people are "getting tired" of trials and feels they will taper off eventually as witnesses grow old and the will to prosecute falters.

Momcilo Krajisnik feels the moment to stop has come, in the interests of reconciliation, and that carrying on with these cases "is still war, but by different means".

It would be tempting to agree - except that would leave so many who suffered with no means of legal redress.

Mark Urban's report will be on Newsnight on BBC Two at 22:30 on Thursday 16 November and available later via BBC iPlayer.