The man who migrated twice

BBC

BBCThis is the story of the man who migrated twice.

Who dodged the police along the Italian border with France - twice. Avoided officials on the train to Paris - twice. Made it to the shanty town life in Calais - twice. Risked death as he stowed away on a vehicle to Britain - twice.

Now he waits for the British asylum process to decide whether he can stay. Yes, again, for a second time.

It is a story of the determination to make it to safety - wherever that is perceived to exist - and of why Europe's migration crisis is only deepening.

First the man himself.

Let's call him Adam, because he doesn't want me to use his real name, and because it's a popular name in Darfur, Sudan, from where he comes.

He calls himself a "village man". But today, in a smart well-ironed shirt, Adam looks at home here in the UK, although the UK has become anything but home for him.

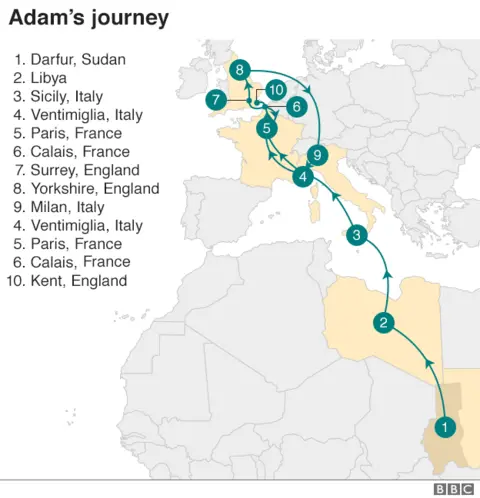

Adam left Darfur in 2012, made his way to Libya, and spent some years there. But as that country crumbled, he felt propelled onwards, to Europe.

He followed the route so many take. Sicily to Ventimiglia in northern Italy, on to Paris, then Calais and then finally Britain.

Only it was not finally.

He was detained by the authorities, put into indefinite detention for four months, then released. He was then arrested again, detained this time for two months before it was decided that he should be sent back to Italy because there was a record (his fingerprints) that he had first arrived there.

"They put me in handcuffs," Adam says. Four officers accompanied him back to Milan and left him there.

"I stayed 10 days in Milan, on the streets." That was when he decided to go back, first to Ventimiglia, and this time round it was harder.

He says: "The first time I was lucky. I just took the train from Ventimiglia to Paris."

But this second time was another year into Europe's migration crisis and the border was being monitored more effectively. "I tried maybe two or three times to get to Marseille, but they sent me back again."

Finally he stepped on to the railway tracks and started walking. "I just walked from Ventimiglia to Cannes for like eight hours." From there to Paris again and on to Calais.

It was more difficult there too. The previous year "it was better. But this time was more difficult because many people (had) come and many police officers (were there) to stop people".

He tried "for like 15 days, 20 days", until he managed to crawl into a space underneath a bus. "And I found myself in UK the second time."

One month and one day after he had been deported from Britain, he was back. But this is not the end of Adam's story.

Determination, desperation, there's no one word that encapsulates fully what you find today along the trail that Adam knows so well. His analysis, that it's getting harder to cross borders, is echoed by others and this is why.

Italy has become the go-to country for those seeking to come across the Mediterranean. The Turkey-Greece route is all but shut down following an agreement between the EU and Ankara.

This year, more than 93,000 migrants have arrived in Italy according to the United Nations. An EU-wide relocation scheme that should have taken the pressure off Italy has moved fewer than 8,000 since it launched almost two years ago.

Rome is trying to do deals with Libya to stop the boats launching in the first place - but there's no central figure of authority in that war zone. They want other countries to open ports in the Mediterranean to migrant and rescue boats - France and others have said no.

So Rome has dispersed its migrants across the country. There is growing resentment in towns and villages where people suddenly find themselves hosting others who don't speak their language. As one man in the north of Italy put it: "I'm not against immigration, but I'm against it when it's handled like this."

The asylum process is stretched to breaking point. Shelters can't accommodate everyone. In Trento, towards the Austrian border, four men, from Bangladesh, Ivory Coast, Ghana and Nigeria, told how they have waited almost three years in limbo - unable to work - not knowing if their final appeal will grant them the right to remain or not.

"If I'd stayed here six months and they told me 'we are sending you back to Ghana' (then) there is no crying," says Ibrahim Mohammed. But after three years? "How can you tell me to go back?"

The likelihood is they will not be deported, even if their asylum appeals fail. Few are actually sent back. Instead they are stuck, unable to work, or provide for themselves. All this - and the poor state of the Italian jobs market - explains why so many decide to move on from Italy.

And with numbers growing, that is why Austria to the north and France to the west have both put in more frequent border checks.

The people they are trying to stop gather every morning for a small free breakfast at a refuge in the Italian border town Ventimiglia. Among them on one day recently were Nasser and his two-year-old son Aladin from Sudan.

Aladin - still in nappies - is ill and they desperately need a doctor.

"I've tried twice in the last week," said Nasser. "My sister is in France waiting for us. The police sent us back."

On the small winding roads through the hills to France, the police check vehicles for stowaways before you can cross the border. They have set up camp in the olive groves up on the hillsides to keep watch for those trying to get across. Occasionally a patrolling helicopter passes overhead.

For France too is "overwhelmed" - that's the word the new president uses - and is trying to stop people coming on to its territory.

In the capital a week ago, they moved thousands off the streets around a metro station into shelters, but now another thousand are back on the streets, according to the deputy mayor, Patrick Klugman.

"What's going now today, this week, this summer, we need urgent measures. We cannot handle it by ourselves in Paris."

The French prime minister last week announced a series of new measures - cutting the time it takes to process asylum claims, "systematically" deporting so-called economic migrants and building more shelters to house refugees in the next two years.

However, Mr Klugman says it is not enough.

Only a tiny number of the hundreds of thousands of migrants and asylum seekers in Europe follow Adam for the whole of his journey and cross from Calais to the UK.

We don't know how many of them do it twice.

As for Adam, there is no happy ending to his story. It has been around a year since he had his last interview in his new asylum process. Since then he has been in limbo, not knowing whether he will be deported again, or this time be allowed to stay.

He has a room to stay in - paid for by the government - and £75 a week to live off. He is not allowed to work. And he says it feels as if he is still on his journey, heading where he does not yet know.

"I have nothing to do. Just eat, sleep, nothing. Wait, wait and nothing changes." "Sometimes you feel it's not a life. It's better to pass away."