France using state of emergency against peaceful protests, Amnesty says

Reuters

ReutersFrench officials have used the state of emergency imposed after the Paris attacks of 2015 to curb peaceful demonstrations, a rights group says.

Amnesty International said hundreds of decrees were issued under the emergency laws, banning public assemblies or individuals from protests.

France's interior ministry has not yet responded to a BBC request for comment.

The state of emergency allows searches without a warrant and people to be placed under house arrest.

It is set to expire on 15 July but President Emmanuel Macron has said he will ask parliament to extend it for the sixth time until November.

The measure was introduced after the attacks of 13 November 2015, when militants from so-called Islamic State (IS) killed 130 people in gun and bomb attacks around the capital.

According to Amnesty's report, between November 2015 and 5 May 2017 there were 155 decrees issued under the emergency powers prohibiting public assemblies.

There were also 639 measures aimed at preventing individuals from taking part in public assemblies, the majority of them related to protests against proposed labour law reforms, it added.

"Emergency laws intended to protect the French people from the threat of terrorism are instead being used to restrict their rights to protest peacefully," Amnesty's researcher Marco Perolini said in a statement.

"Under the cover of the state of emergency, rights to protest have been stripped away with hundreds of activists, environmentalists, and labour rights campaigners unjustifiably banned from participating in protests."

The group also said that security forces used "unnecessary or excessive force" against peaceful protesters "who did not appear to threaten public order".

Living under emergency: By Lucy Williamson, BBC News, Paris

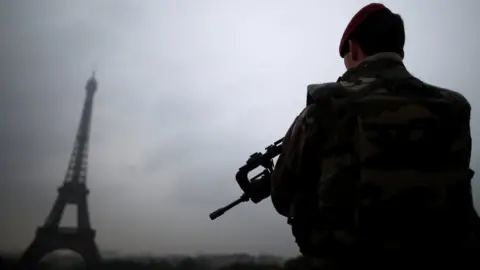

The most visible signs of France's state of emergency have, after one-and-a-half years, become routine; the heavily armed security forces dotted around the capital - outside schools, train stations, tourist sights.

Accompanying them has been the slow drum-beat of concern from human rights organisations over its invisible effects: the public gatherings that were banned and never took place, the people expelled or confined to house arrest.

But if recent polls are to be believed, France is firmly behind its government. Earlier this year, 81% of respondents told the IFOP polling agency that they did not want the state of emergency lifted, and 20% wanted the restrictions strengthened.

Many people accept that the new measures can't stop every potential attack, but with more than 230 people killed by extremists here since January 2015, and the risk of further attacks seen as high, national security has - so far - trumped individual freedom.

The state of emergency

EPA

EPA- Extra police and armed guards in public spaces, schools, universities and transport terminals

- Tightening of border controls and restrictions at airports and train stations

- Homes can be searched by police without a warrant and people can be put under house arrest

- Banning of protests and public gatherings