Indigenous deaths in custody haunt Australia

Supplied

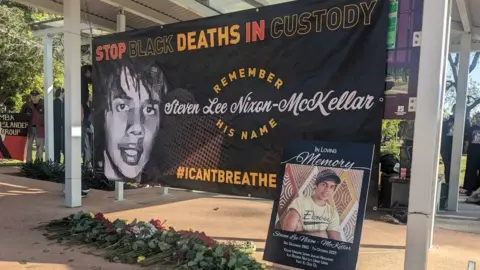

Supplied"It's a pain you can't describe," Raylene Nixon says quietly.

"It's something that you feel deeper than a broken heart - it's pain in your soul."

In 2021, she sat in a sterile room and watched Australian police footage of her son's death in real time, as he gasped for air and pleaded for help.

"Choke him out," one officer can be heard yelling in the body camera video, before another places Steven Nixon-McKellar in a neck restraint.

Moments later, the 27-year-old Aboriginal man lost consciousness. Paramedics failed to resuscitate him, as his throat was obstructed by vomit.

Mr Nixon-McKellar is one of 562 Indigenous Australians to die in custody since 1991 - the year a landmark inquiry, intended to turn the tide on the issue, released hundreds of recommendations.

But few of those proposals have been implemented, studies suggest, and Indigenous people continue to die at alarming rates in prison cells, police vans, or during arrest.

Last year was the most lethal on record, according to government data.

Police advocates insist officers are using necessary force when confronted with life-threatening situations, and that each death is thoroughly examined.

But critics say there is a "culture of impunity" in which "police are investigating police" in cases alleging excessive force. They point to the fact that there has never been a conviction of a police or corrections officer over an Indigenous death in their care.

"We're sending a message to society about what is and isn't acceptable behaviour," criminologist Amanda Porter says.

"And in Australia at the moment - it's open season."

'They only knew the colour of his skin'

Mr Nixon-McKellar died during his attempted arrest following an anonymous call to Queensland police suggesting he had been driving a stolen vehicle.

The officers involved have defended their use of the chokehold - which is now banned - on the basis that he was "fighting" them at the scene, making it difficult to deploy a taser or pepper spray.

Dhadjowa Foundation

Dhadjowa FoundationBut Ms Nixon questions whether they might have acted differently that day, had her son been white.

"The only thing they knew about him was the colour of his skin," she tells the BBC.

The findings from a coroner's inquiry into his death will soon be made public.

His case bears similarities to the death of David Dungay Jr inside a Sydney prison in 2015, a nationally famous incident which has been compared to George Floyd's death in the US.

Like Mr Floyd, Mr Dungay also repeatedly yelled "I can't breathe" in his final moments.

A diabetic, the 26-year-old had been trying to eat a packet of biscuits when six guards entered his cell with a riot shield to restrain him. Five of them then pinned him face down on a bed and sedated him.

"You're the one who brought this on yourself Dungay," one officer can be heard saying in footage of the incident. "If you're talking you can breathe," another adds.

Corrective Services New South Wales has maintained that the death was not suspicious, and an internal investigation found no criminal negligence.

A coroner did find that "agitation as a result of the use of force" was a contributing factor, along with Mr Dungay's pre-existing health conditions - but declined to send the case to prosecutors.

Mr Dungay's family has run a years-long campaign calling for charges to be laid against the officers involved. It led to a petition with over 110,000 signatures being sent to the NSW Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions. The office did not respond to the BBC's request for comment.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlthough Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people don't die at a greater rate than non-Indigenous prisoners, they are much more likely to find themselves in prison or police lock up.

That was one of the central findings of the 1991 inquiry - and it has worsened with time.

Today they comprise 33% of Australia's prisoners, though they are just 3.8% of the national population. Socio-economic disadvantage and "over-policing" are central to the disparity, numerous investigations have heard.

"There's a legacy of colonisation in Australia where First Nations people have always been disproportionately segregated and controlled," says Thalia Anthony, a law professor at the University of Technology Sydney.

She and others argue this has injected racist stereotypes into policing, leading to Indigenous Australians being treated as "deviant, drug addicted, or alcoholics" and paid undue attention.

Reviews are currently under way in Queensland and the Northern Territory to address allegations of widespread racism within both forces.

Western Australia Police has introduced strategies to address institutional racism, and Victoria Police's chief commissioner recently offered an unreserved apology to Aboriginal families for "undetected, unchecked and unpunished" systemic discrimination.

Federal and state governments have introduced some services aimed at lowering Indigenous incarceration rates. Most recently, Canberra committed to funding community-led programmes designed to tackle the root causes of offending and disadvantage.

"Too many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are being robbed of their futures by a system that has let them down," Indigenous Affairs Minister Linda Burney told the BBC.

Experts have welcomed such initiatives, but many also call for broad reforms to bail conditions and the decriminalisation of minor offences which they say stem from social issues such as homelessness.

Ms Burney said that state governments, which oversee local laws and policing hold "most of the levers".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd voter sentiment is one reason why states are still creating "new offences, increasing sentences and building more jails" despite falling crime rates, explains Prof Luke McNamara from the University of New South Wales.

He describes the conflict between the two approaches as "an unresolved paradox" that is playing out in real-time.

'No-one gets justice'

David Dungay Jr's mother, Leetona, has now taken his case to the United Nations, filing a motion against state and federal governments for violating her son's right to life. It will be decided in the coming months.

She hopes it will force Australia to confront its record on Indigenous deaths in custody and fix "systemic failures".

"I want to get justice for David," Ms Dungay tells the BBC. "It was murder. No-one attempted to help my son."

But if you ask Corina Rich, "no-one gets justice".

Her son Brandon died after a prolonged struggle with police at his grandmother's property in rural New South Wales in 2021.

Two officers had been called to respond to a domestic dispute. Their attempts to arrest Mr Rich ultimately resulted in him being stripped of his clothes, pepper sprayed, and pinned down.

When he lost consciousness, police say they immediately tried to resuscitate him and failed. But they didn't wear body cameras - despite it being policy - meaning the details of the 29-year-old's final moments rely almost solely on the officers' testimony.

NSW Police said that "remedial action" was taken against both for the camera violation.

Last month, a coroner found Mr Rich had died of physical exertion and stress, but that it was not possible to determine whether the use of force applied by police was a contributing factor.

Supplied: Corina Rich

Supplied: Corina RichFor Ms Rich, questions remain, and she relives that day on repeat - often in violent nightmares.

"I'm in my son's position, when he's dying on the ground. I don't have a life anymore. Your whole world is gone, broken."

When asked about the possibility of legal action, she almost laughs: "Nothing's going to happen to the police. It never does.

"I don't think we'll ever see change, as much as we want it. The whole system sucks."

It's a view shared by many Indigenous families and advocates, who feel hope is hard to come by.

But several experts told the BBC that in the short team at least, a warranted conviction of a police or prison officer over an Indigenous death in custody could be "groundbreaking".

"It would send a message that police are not immune from the criminal justice system," Prof Anthony says.

She cautions that few cases make it to trial and when they do it's rare for "police not to be believed" by what are usually "non-Indigenous juries".

Australia's national police union declined to answer questions from the BBC.

Ms Nixon is convinced that a reckoning won't come until there's sustained public outrage over every Indigenous death.

"When you're only 3% of the population, you rely on the other 97% to do the right thing," she says.

"It comes down to human compassion [but] there's still a blame the victim mentality - as though what happens to us is what we deserve. Maybe future generations will change that narrative."