The trip that transformed Australia and China ties, five decades on

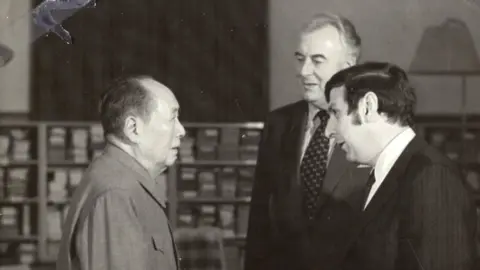

Stephen Fitzgerald

Stephen FitzgeraldA young Australian researcher was having a late-morning drink in a Canberra pub in 1971 when he received a phone call that changed his life.

"The pub called out: 'Is there someone here called Stephen FitzGerald?'"

One of Australia's most powerful politicians - future prime minister Gough Whitlam - was on the line.

Mr Whitlam, then opposition leader, asked the China expert whether he would join him for a historic diplomatic mission to the country.

"I said yes, of course I would!" Dr FitzGerald told the BBC.

"Then he said in his kind of inimitable wisdom: 'Would you mind travelling economy class?'"

That moment would help set the ball rolling for Australia to forge diplomatic ties with China. It achieved that 50 years ago - on 21 December 1972.

'Deeply divisive' issue

The trip was a risky political move for Mr Whitlam.

In 1971 the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was forcing its way on to the world stage amid the Cold War, seeking improved foreign relationships and a seat at the United Nations.

But it faced hurdles from key players like the US, which refused to recognise the CCP as China's legitimate government.

Australia was one such nation. China remained a "deeply divisive" issue there, Dr FitzGerald says.

At the time, just 3% of its population was born outside Australia or Europe - and many people were suspicious of other cultures. The "red menace" of communism was also a great concern. Such fears intersected over China.

For many, it resonated when Australia's conservative government spoke of the threat posed by the "downward thrust of China", Dr FitzGerald says. It was easy to "conjure up the idea of Australia being taken over by Chinese, and not just Chinese, but Chinese who were communist".

"It was a powerful message… even though it was not remotely possible."

The Whitlam Institute

The Whitlam InstituteOn the other hand, Mr Whitlam had long advocated for Australia to take up relations with China.

It was not because of any ideological sympathy for the CCP, Dr FitzGerald says. "You don't have to like them... [But] his view was, how can you not have diplomatic relations with the government of a country of that size?"

But even within Mr Whitlam's Labor Party, many regarded any step towards China as "political death" domestically.

"So it took courage on many fronts," Dr FitzGerald says.

The accidental ambassador

Mr Whitlam's path to China may have seemed inevitable, but Dr FitzGerald's was somewhat of a fluke.

He didn't choose to study China. It all snowballed from the moment he was assigned Chinese language classes on his first day as a foreign service cadet. And by the time Mr Whitlam came calling, Dr FitzGerald had left for a career in academia.

But if the invitation was a surprise, the trip itself felt even more surreal.

"In those days you had to walk into China, there were no flights," Dr FitzGerald says. "We had to go to Hong Kong, take the train up to the border, carry our luggage across, go through immigration and customs on the Chinese side and then board another train."

The delegation toured businesses, factories, schools and tourist sites for two weeks. Dr FitzGerald recalls constantly explaining Australian sense of humour to "mystified" Chinese officials.

But the real goal of the mission was to meet then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai. It was never clear if that would happen - until Chinese officials arrived at the Australians' hotel late one night and began ushering people into cars.

"We drove across the empty Beijing streets to the Great Hall of the People, went up the stairs, through dimly lit corridors into a room, and Zhou Enlai was standing there," Dr FitzGerald says.

When the much-anticipated meeting began, Mr Zhou surprised the delegation by inviting journalists to stay in the room.

Stephen Fitzgerald

Stephen FitzgeraldThe meeting transformed Australia's feelings towards China.

"The Chinese had been demonised as a cross between red devils and yellow perils - almost as if they had horns. And here was this most sophisticated and civilised, polite and diplomatic, courteous, charming person.

"When I watched that meeting between Whitlam and Zhou Enlai, I concluded that relations with China would never be the same again.

"All that stood between us and diplomatic relations at that stage was the election during December of 1972."

Mr Whitlam did win the election, ending 23 years of conservative rule. Within weeks, on 21 December, he recognised the People's Republic of China.

Soon after, he sent Dr FitzGerald to Beijing as Australia's first ambassador to the country. Just 34 at the time, he remains Australia's youngest ambassador ever.

"Of course it was daunting. It couldn't not be," he says. "But I think that sense was really overwhelmed by the excitement."

Stephen Fitzgerald

Stephen FitzgeraldMr Whitlam's hope was that Australia would build a relationship with China that was comparable to those it had with other major powers, Dr FitzGerald says.

But 50 years on, that's not where things are.

Lessons for today?

Australia and China have benefited enormously from trade with each other, but bilateral relations have sunk to record lows in recent times. High-level contact was cut off for two years, amid disputes over trade, human rights and foreign interference.

But last month Prime Minister Anthony Albanese - who was elected in May - became the first Australian leader to have a face-to-face meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping since 2016.

He said it was a "warm" and "very constructive" chat, but there was no movement on key issues for Australia. Many experts have little optimism that the relationship will significantly improve any time soon.

Jennifer Hsu, a research fellow at Australia's Lowy Institute thinktank, told the BBC at the time that too many points of conflict remain. Many of them, she says, are rooted in "fundamental" differences such as systems of government or values.

"Those issues aren't going to be resolved by one meeting or even several meetings."

Another such meeting will take place on Wednesday when Australia's Foreign Minister Penny Wong meets her Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, in Beijing. It marks the first visit by an Australian minister to China's capital in more than three years.

Dr FitzGerald says the China of today seems more "dictatorially minded" and "assertive", but he still thinks there are lessons in what transpired 50 years ago.

"The [Whitlam] government recognised that no matter what has happened, you still have to have relations with the government in that country.

"It didn't mean that everything was sweetness and light, but it meant that we were talking with each other."