Australia election: How climate is making Australia more unliveable

Sam Bowstead

Sam Bowstead"It's devastating. The amount of time and effort you put in your home and then to see it go under water."

Sam Bowstead is an architect who specialises in preparing houses to withstand natural disasters. But when floods engulfed his Brisbane home in February, he felt helpless.

"I've worked with people who've been in similar situations - now this happened to me," he says.

"I was shocked at how fast [the water] rose... more than a metre in a couple of hours. I went from being worried about our property to being worried about our safety."

In the end, a boat was the only way out.

Mr Bowstead's experience has become increasingly common for Australians.

In the past three years, record-breaking bushfire and flood events have killed more than 500 people and billions of animals. Drought, cyclones and freak tides have gripped communities.

Climate change is a key concern for voters in Australia's election on Saturday. So is the cost of living - and these issues are converging like never before.

Australia is facing an "insurability crisis" with one in 25 homes on track to be effectively uninsurable by 2030, according to a Climate Council report. Another one in 11 are at risk of being underinsured.

Insurance for the highest-risk homes will be prohibitively expensive or refused by providers, says the Climate Council, which created an interactive map for Australians to search.

"Climate change is playing out in real time here and many Australians now find it impossible to insure their homes and businesses," says chief executive Amanda McKenzie.

The state most exposed

Nowhere is this a bigger issue than in Queensland. It is home to almost 40% of the 500,000 homes projected to be effectively uninsurable.

Queensland has been ravaged by floods in recent months. In February, the state capital Brisbane had more than 70% of its average yearly rainfall in just three days.

"I still feel quite traumatised when it rains heavily," says Michelle Vine, whose East Brisbane home was destroyed along with decades of her artwork.

"We had to move out of the home - it became unliveable."

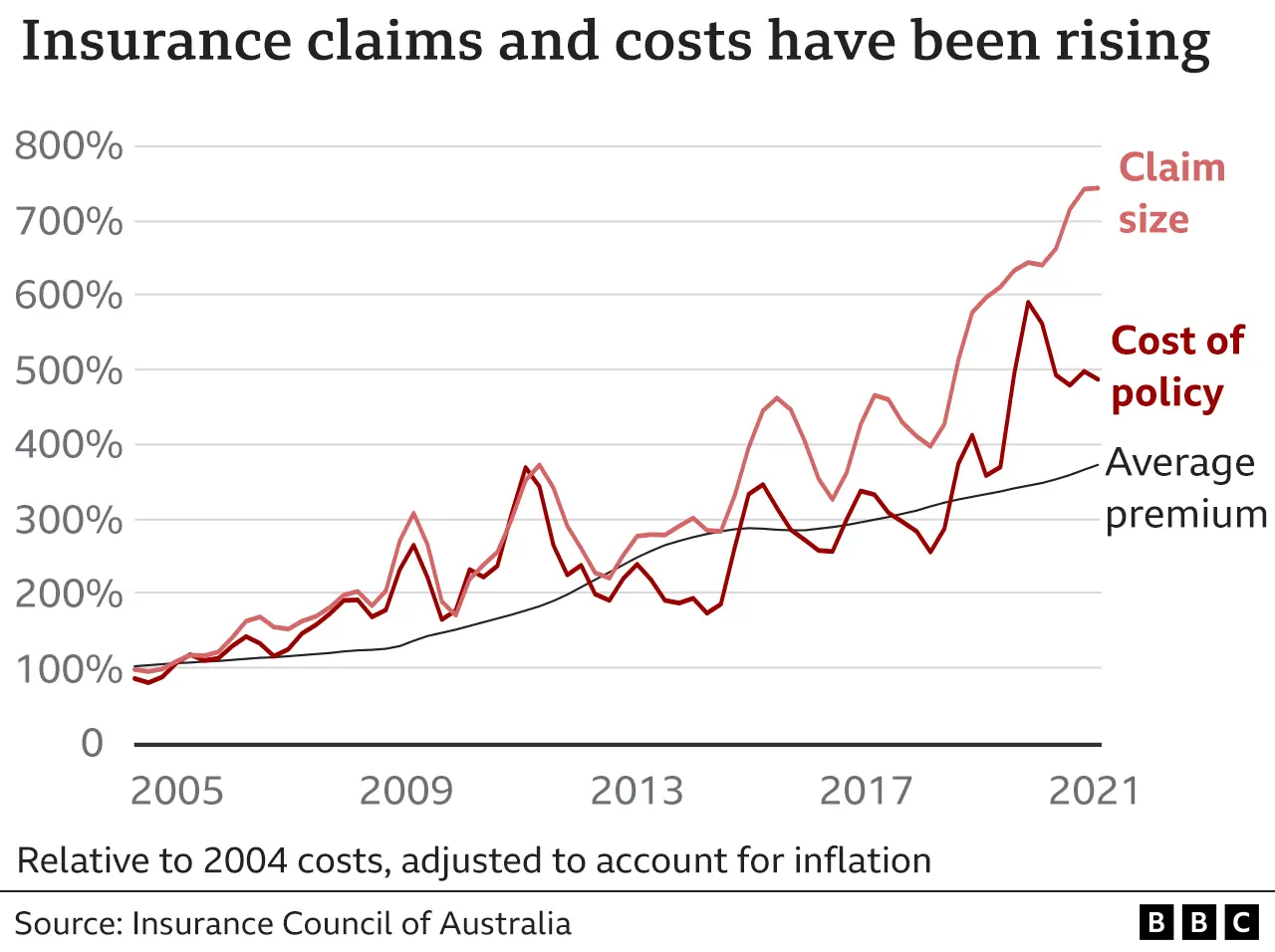

Insurers say the floods - which also battered New South Wales - will become Australia's most expensive flood event ever. But even before this year, insurance costs were skyrocketing.

Though rising property prices are one factor, Australia's peak insurance industry body points the finger at climate change.

The Insurance Council of Australia says no parts of the country are currently uninsurable but there are "clearly affordability and availability concerns".

Over the past decade, the amount paid out by insurers on damage claims from natural disasters has roughly doubled.

On average, consumers now pay almost four times for home insurance premiums than in 2004.

In northern Australia, these numbers are even more extreme - in some cases 10 times higher than elsewhere.

More Australians are being forced to underinsure - purchase cheaper policies that cover too little - or forgo insurance altogether.

"This is probably Australia's most important cost-of-living issue," Dr Antonia Settle, a political economist at the University of Melbourne, tells the BBC.

"Households that don't have insurance risk losing their most important asset."

'Catch-22 for young people'

The phenomenon could also exacerbate social inequality and create "climate ghettos", says Climate Valuation, a risk analysis company.

Properties in higher-risk areas are becoming cheaper to buy and rent, often attracting people who are least able to afford adequate insurance, compounding the financial impact of disasters.

"People are not moving away from climate-endangered places in Australia. And in fact, along the fringes of the major cities, they are more likely to move toward them," says demographer Liz Allen from the Australian National University.

"The housing affordability issue in Australia is so dire… that people see climate catastrophe as almost a bargain, a way to ensure that they can have a place to call their own."

Ms Vine is one example of this - saying she was drawn to a vulnerable area by price. At the time, she felt like she'd "won the lottery". Mr Bowstead made a similar choice, describing it as "a Catch-22... for young people".

And once in a risky area, it's near impossible for many to get out - as is the case for Gary Godley in the town of Grantham, west of Brisbane.

Given Grantham's horrific flood history - 12 people died there in 2011 - there are no takers for his home.

"We want out. We just can't afford it," Mr Godley says. "We can't do anything."

So what can be done?

The government has promised billions to help "reinsure" insurers against major claims resulting from disasters, arguing it will essentially halve premiums for people in northern Australia.

But it is a risky policy, and not one either the Insurance Council of Australia or the country's industry watchdog wanted.

Critics have pointed out that disasters are now frequently devastating areas outside northern Australia that won't be covered by the policy. What about their premiums?

They're instead calling for the government to limit development in high-risk areas, consider buying out some homeowners, or create incentives for people to make their properties disaster-resilient.

But the obvious answer is addressing climate change, Dr Settle says - though this is something successive governments have been reluctant to do.

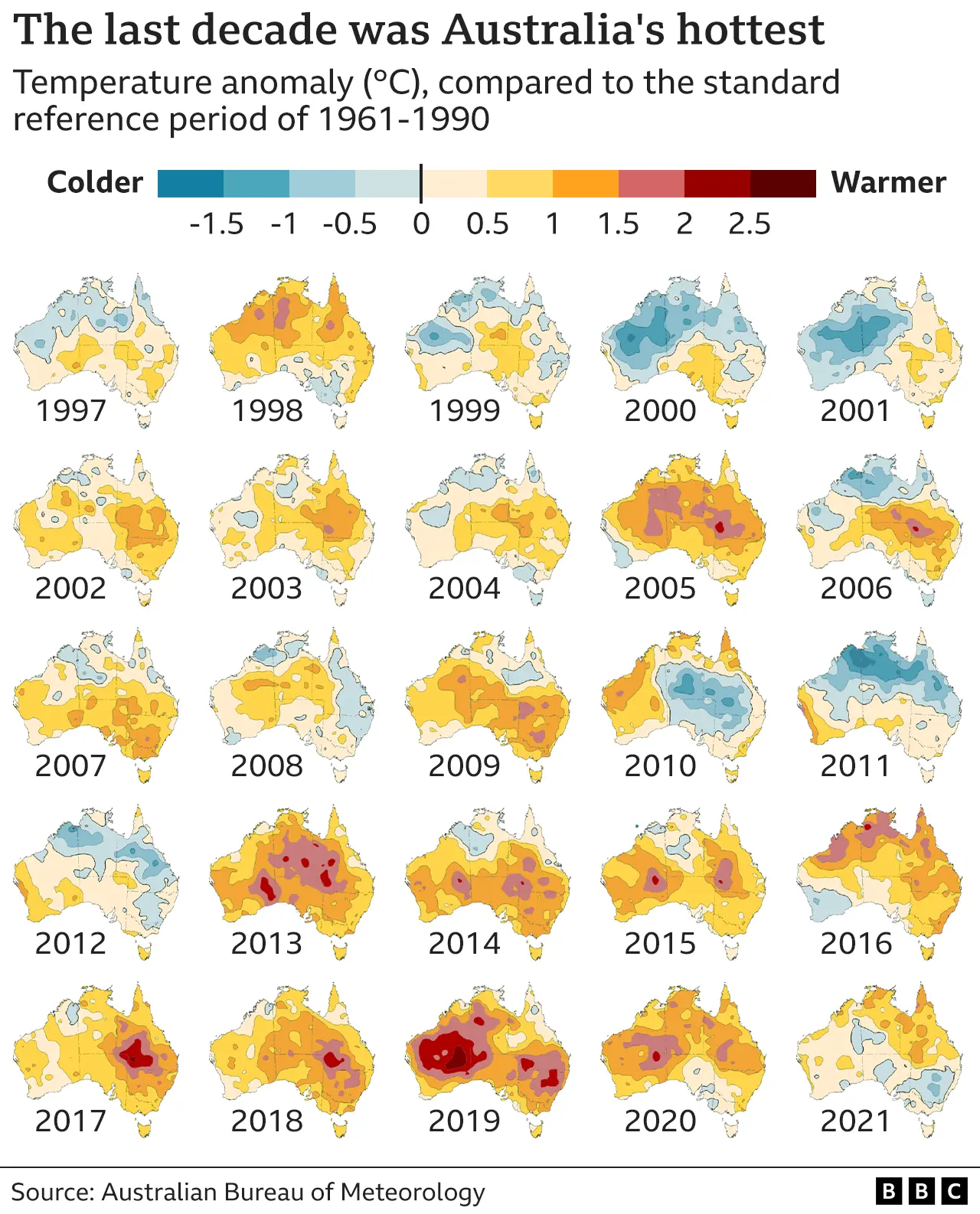

After massive bushfires in 2019-20, Australians were warned to prepare for an "alarming" future of simultaneous and worsening disasters.

Yet for a nation so exposed to climate change, Australia remains one of the world's biggest emitters per head of population.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison's government has promised to reduce emissions by 26% by 2030. Labor, under Anthony Albanese, has pledged a 43% cut.

Both are below the 50% recommended by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The coal problem

Most Australians want tougher climate action, but both parties have kept fairly quiet on the topic during this election campaign.

In the town of Gladstone - which lies in a marginal seat in central Queensland - the reason for this avoidance is clear.

Coal is an integral part of Gladstone. It's shipped from the local port and has helped Australia become the second-largest exporter globally and created thousands of jobs.

Phil Golby, a local Australian Manufacturing Workers' Union official, says "change is inevitable" but fears fossil fuel workers will be left behind.

"I've heard a lot of talk. I've listened to a lot of presentations - but I haven't really seen a direct path yet," Mr Golby says.

"If a new industry comes [to Gladstone] we need to make sure that we're going to get our workforce trained… [and] it's got to replace their pay. We can't start to see people going backwards."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEssentially, coal lies in that impossible place between Australia's prosperity, politics, and environmental perils.

So phasing out fossil fuels is a politically toxic issue that no big party wants to tackle head-on, especially not during an election.

That frustrates Mr Bowstead. For him and so many young people there's a real anxiety about what climate change will mean for how and where they'll live in the future.

"[It's] not going to happen - this is happening already," he says.

"It feels like we're going to have to take responsibility and bear the brunt of that for much longer than most of those people who are in power now."

With visual journalism by the BBC's Erwan Rivault, Paul Sargeant and Alison Trowsdale.