Coronavirus and climate: Australia's chance to shift to green energy

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Covid-19 pandemic is a "huge opportunity" to fast-track Australia's shift towards more renewable energy, climate scientists have told the BBC.

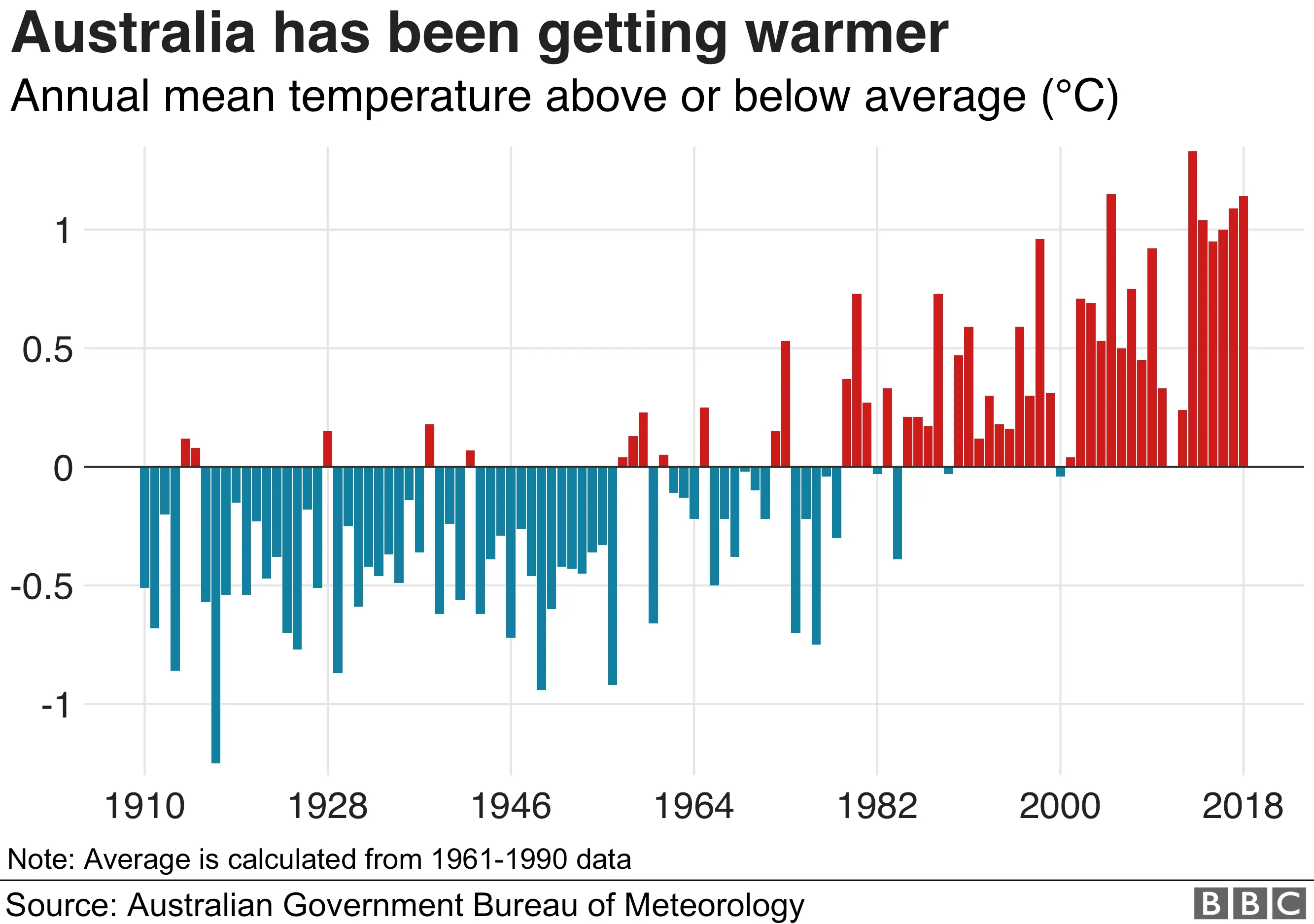

Australia's recent bushfires made climate change the country's most pressing issue.

But scientists say that momentum risks being lost because of the virus.

Instead, as Australia looks for ways to revive its economy, innovations around solar, wind and hydroelectric projects should be central, they say.

The devastating summer of blazes - driven by drought and rising temperatures - killed 33 people and destroyed about 3,000 homes. Millions of hectares of bush, forest and parks burned.

Prof Mark Howden of the Climate Change Institute at the Australian National University said memories of "the droughts and the fires and the smoke haze across major cities have dissipated with the arrival of Covid-19".

"And clearly the momentum for change in relation to climate here in Australia has dissipated quite considerably too."

'Significant disruption is an opportunity'

Australia contributes about 1.5% of the world's total carbon emissions. Fossil fuels it exports - mainly coal to China and India - make up another 3.6% when burned.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProf Howden told the BBC that reducing carbon emissions should be put front and centre of Australia's post-virus economic recovery plan.

"When you have significant disruption like this, it does give you an opportunity to move forward on a different trajectory from the one you're on previously," he said.

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health

- VISUAL: The world in lockdown in maps and charts

While the use of renewables is increasing in Australia year-on-year - last year 24% of all electricity generated came from renewable sources - the current Liberal-National government has been notoriously reluctant to phase out coal in favour of cleaner options.

Last year, it gave Indian company Adani the final approval for construction to begin on a controversial coal mine in Queensland. And a recent report suggested Australia was second only to China in the number of new coal-powered plants in development.

Prof Matthew England of the Climate Change Research Centre said it would be " disastrous" if, once the pandemic is over, Australia throws money into "lazy, low tech" coal to get the economy moving again, "because we know that those carbon emissions will change our planet's climate in very dangerous ways".

Australia is faring far better during the pandemic than many nations - with fewer than 6,800 confirmed cases and 83 deaths reported as of late April.

Chief Australia Economist at BIS Oxford Economics, Sarah Hunter said the Australian government now had the "headspace" to focus on its long-term economic response.

"Serious discussion around energy policy" should be part of measures to support recovery and growth, she said, especially while there was a a fairly "co-operative environment" between the government, opposition and industry.

"Obviously nobody wanted what's happening right now. But if it does mean that we get an acceleration of some of these reforms, that can be very positive in the long run."

'Robust balance' of economy and climate

So far Australia's economic response has centred around a A$130bn ($82bn: £66bn) support package - with a subsidy for employers to keep people in work.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProf Howden fears this may be short-sighted.

"Instead of putting money through businesses, essentially just to keep people in their current jobs or keep those job relationships going, we could put some of that money into nation-building activities, which reduce our emissions and give us future options," he said.

"This is exactly the time when we should be having those discussions and making those plans."

"Once we're through the immediate effects of the coronavirus and the lockdown, in some ways that's going to be too late."

But Grattan Institute think tank energy director Tony Wood the best option for Australia was a "robust balance" of energy options.

While he supported investment in gas and other sectors including hydrogen and batteries for electric vehicles, he argued more renewable energy projects do not make economic sense right now.

"I don't see why we should throw more money at more renewables" Mr Wood told the BBC.

"I don't think it needs more subsidies or governments building wind and solar farms. They in themselves don't create many jobs beyond the construction phase, and even those jobs are not well paid."

'Perfect storm'

Ultimately, it may be cold hard economics rather than environmental concerns that bring most change.

With Australia's first recession in almost 30 years predicted as a result of the pandemic, analysts suggest this in itself could threaten the long-term future of many coal power stations.

Lower demand from industry forcing down electricity prices for a prolonged period would make renewables a cheaper, more enticing option - what energy analyst group Reputex call "a perfect storm for the wholesale electricity market".

Also potentially bringing down Australia's demand and therefore emissions, are behavioural changes picked up during lockdowns.

As in other parts of the world, Australia has seen industry slow and air travel all but stop.

Given that carbon stays in the atmosphere for thousands of years, this small blip is negligible, says Prof England, who expects to see pent up demand for travel and consumption post-lockdown.

But he predicts, for example, that people flying between Sydney and Melbourne for short meetings will become less common once businesses see that video conferencing is just as effective.

A new trust in experts?

While more than 200,000 people worldwide have died from Covid-19, the World Health Organization forecasts that an additional 250,000 people will die each year from 2030 if global temperatures continue to rise.

Despite such dire warnings, there are few signs that people will take climate as seriously as they have this pandemic.

A poll last week from Ipsos Mori suggested only 57% of Australians felt government actions after the pandemic should prioritise climate change.

"We need to understand this is a huge problem that we're burdening our kids with," says Prof England.

"And even if it's not necessarily in your backyard, it will be at some stage. And the bushfires last summer, I hope, brought that home for Australians."

But he sees some cause for optimism.

"Climate change, unfortunately, has had three or four decades of the best scientific advice being ignored by many nations around the world in favour of some of the fossil fuel industry's push for longevity," he said.

"We've seen with this pandemic that those nations that took the expert advice seriously acted quickly and acted early are the ones who've best had been able to cope.

"Now, one of the big things that people realise is that listening to experts is a good thing to do."