Aboriginal Australians born overseas cannot be deported, court rules

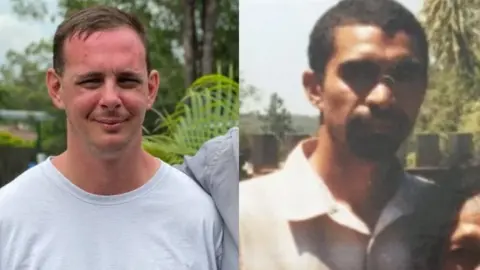

ABC News/Love family

ABC News/Love familyAustralia's High Court has said Aboriginal people hold a special status under the law so cannot be deported - even if they are not citizens.

The ruling is being seen as a historic moment for the recognition of Australia's first inhabitants.

The case relates to an appeal by two men who have Aboriginal heritage but foreign citizenship, and were to be deported over their criminal record.

The government said the ruling created "a new category of persons" under law.

What was the original court case?

Brendan Thoms and Daniel Love - who had no prior connection - were born in New Zealand and Papua New Guinea respectively but moved to Australia as children.

Each man has Aboriginal heritage and one Australian parent. Both have children who are Australian citizens and were themselves permanent residents.

The two men both had criminal records and had both served jail sentences for violent assault.

Under controversial Australian laws, foreigners - or aliens - must lose their right to live and work in the country if they are sentenced to a year or more in prison.

Both men had their visas cancelled in 2018, but appealed against the order.

What did the court rule?

The High Court had been asked to rule for the first time on whether, as indigenous people, Love and Thoms could really be considered "aliens" under the constitution.

EPA

EPAThe men's lawyers argued that the men could not be considered alien because of their deep ancestral roots to Australia.

The judges ruled four to three that Aboriginal Australians were "not within the reach" of the constitutional references to foreign citizens.

"Aboriginal Australians have a special cultural, historical and spiritual connection with the territory of Australia, which is central to their traditional laws and customs and which is recognised by the common law," said the ruling.

The existence of that connection, they said, meant Aboriginal Australians could not be classed as "alien" under the law.

Acting Immigration Minister Alan Tudge said the ruling "created a new category of persons; neither an Australian citizen under the Australian Citizenship Act, nor a non-citizen".

The government was still considering the implications, he said, and would "consider the best methods to review other cases which may be impacted".

What does this mean for Thoms and Love?

Though the ruling will only directly affect a small number of people, it is being seen as a step forward for the legal recognition of indigenous Australians overall.

Claire Gibbs, a lawyer for the two men, told reporters afterwards: "This case isn't about citizenship, it is about who belongs here.

"What this means, and what the real significance of this case is, is that Aboriginal people, regardless of where they are born, will have protection from deportation."

For Brendan Thoms the issue is clear cut - he has been released from detention and will not be deported to New Zealand.

He comes from the Gunggari people, and has legally recognised traditional rights to Gunggari land.

"Brendan has had 500 sleepless nights worrying he could be deported at any time, and that is now thankfully at an end," said Ms Gibbs.

"He is very happy to have been released and to now be reunited with his family at long last."

However it remains unclear what this means for Daniel Love.

He comes from the Kamileroi people, but the judges could not agree whether he had been accepted as a member of the tribe, so could not say whether he qualified for the special status.

What is the status of Aboriginal people in Australia?

Aboriginal Australians lived in the country for at least 47,000 years before the arrival of European settlers, and subsequently suffered centuries of violence and oppression.

Aboriginal Australians and Torres Strait Islanders make up about 3% of the population, and are among the nation's most disadvantaged.

Consistent government reports have found that indigenous people are disadvantaged across the board, from child mortality rates and life expectancy, to literacy, academic success and employment rates.

Australia has never reached a treaty with its indigenous peoples, which many argue this would bring important recognition. Work has begun on a treaty in the state of Victoria.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders are also not recognised in the constitution, though there is ongoing debate about doing so.

More BBC stories on Aboriginal people and culture