Australia's heated same-sex marriage debate

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwenty years after Tasmania became the last remaining Australian state to decriminalise male homosexuality, the country is having its say on same-sex marriage.

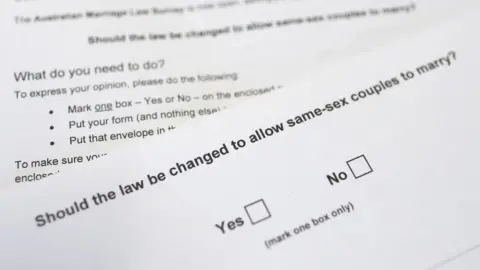

Voting is under way in a non-binding, voluntary postal survey to measure support for reform. It has been, at times, an ugly and bruising process.

On Friday, the Australian media was awash with reports of an alleged headbutt on Tony Abbott, the former Australian prime minister and opponent of same-sex marriage. A 38-year-old DJ called Astro Labe was charged following the incident.

Witnesses said he was wearing a badge supporting same-sex marriage, but he told Australian media that his actions were not connected to the debate and he did it "because I didn't think it was an opportunity I'd get again". Mr Abbott described the incident as "politically motivated violence".

Elsewhere, employees have complained they face punishment or unfair treatment at work if they don't show their backing for a "Yes" vote, while police in Sydney were called to a confrontation between rival groups at the University of Sydney.

"The vitriolic abuse people experience for holding views in opposition to the legalisation of same-sex marriage is phenomenal," said Karina Okotel, a federal vice president of the governing Liberal party, and a prominent figure in the "No" campaign.

"A culture has developed whereby it is acceptable to vilify, mock, abuse and shame anyone who stands in the way, or even raises questions, about whether we should legalise same-sex marriage. I've been called a homophobe, a bigot and been told that my views are disgusting."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe government has pleaded for the debate to be civil and respectful, while the Senate, Australia's upper chamber, has gone a step further. It has passed special legislation that bans intimidation, threats and vilification during the vote, which runs until early November.

Advertisements will also need to be vetted and broadcasters must ensure opposing views are shown or heard on air.

In May, Alan Joyce, chief executive of Qantas, Australia's national airline, who is gay, was ambushed during a speech at a business breakfast in Perth by a man who threw a lemon meringue pie in his face.

His assailant was reportedly a church-goer opposed to gay marriage. Qantas is one of 1,300 companies to have joined the push to change the Marriage Act to include same-sex couples, and Mr Joyce has been worried that the postal vote would incite resentment and hostility on both sides of the argument.

Getty Images

Getty Images"One of the reasons why we weren't big supporters of the postal ballot was that we were worried the tone wouldn't be respectful and wouldn't be engaging and I think clearly on both sides, the extremities of both sides, that's the case and that is worrying.

"I think there are a lot of vulnerable people in our society, and unfortunately I think they're going to be impacted by this," he explained.

Like other proponents of the Equality Campaign, Alan Joyce believes there has been such a consistently high level of community support for change over time that a vote in parliament, not a survey of public attitudes, was the most effective way to drive marriage reform.

This is the first time the government statisticians have been put in charge of a national ballot, instead of the Australian Electoral Commission.

"It is partly due to a lack of political courage. In other countries the politicians had the courage to make the decision as elected members on behalf of the people," explained Vince Mitchell, a professor at the University of Sydney Business School.

Australia inherited anti-gay laws from British colonisers, who arrived towards the end of the 18th Century.

Until 1949, the death penalty remained on the statute books for sodomy in the southern state of Victoria, but bold legislative change did eventually come in September 1975, when South Australia declared that male homosexuality would no longer be a crime.

It would take the island of Tasmania another 22 years to do the same. In between, police arrested more than 50 people at the first Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras parade in Sydney in 1978.

Prof Mitchell believes that, although controversial, the postal ballot could have a cleansing effect on a country that continues to harbour unease and mistrust about same-sex relationships.

"Still within (Australian) society there is some latent phobia about what gay relationships stand for," he told the BBC. "It has become politically incorrect and not acceptable to criticise the LGBT community and that lulls people into a false sense of security and a sense that this issue has now been resolved."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSixteen million Australians are eligible to participate in the survey. Opinion polls are predicting a win for a "Yes" campaign based on messages of equality, inclusion and human rights. But unlike Australian elections, voting in the postal survey isn't compulsory, so complacency and a low turn-out could be decisive factors.

The anti-reform Coalition for Marriage hopes to convince the undecided that should same-sex couples be allowed to marry there would be serious consequences for children, who would be exposed to "radical" views on homosexuality in schools.

Academics say the fight over gay marriage in Australia is a classic political campaign of "hope versus fear".

"I can assure you that if the postal vote delivers a "yes" vote, and I encourage Australians to vote "yes" and I will be voting "yes", then I have no doubt the legislation will sail through the Parliament," said Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull, whose centre-right government is split over marriage equality.

The result will be known on 15 November. Either way, the outcome will be monumental.