Why India's real Covid toll may never be known

AFP

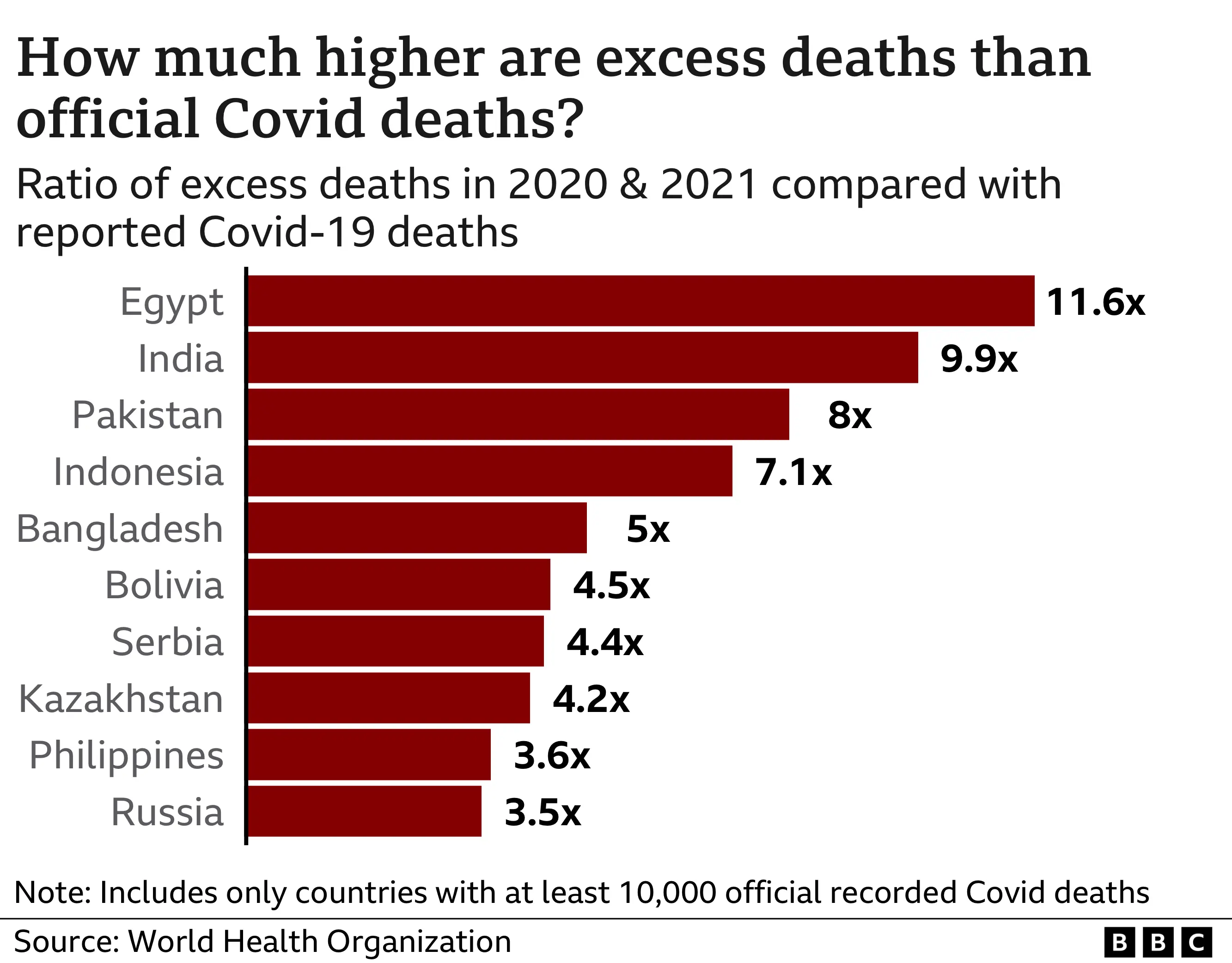

AFPMore than 4.7 million people in India - nearly 10 times higher than official records suggest - are thought to have died because of Covid-19, according to a new World Health Organization (WHO) report. India's government has rejected the figure, saying the methodology is flawed. Will we ever know how many Indians died in the pandemic?

In November 2020, researchers at the World Mortality Dataset - a global repository that provides updated data on deaths from all causes - asked authorities in India to provide information.

"These are not available," India's main statistical office told the researchers, according to Ariel Karlinsky, a scientist who co-created the dataset and is a member of an advisory group set up by the the WHO for its estimates of excess deaths caused by Covid globally during 2020 and 2021.

Excess deaths are a simple measure of how many more people are dying than expected compared with previous years. Although it is difficult to say how many of these deaths were due to Covid, they can be considered a measure of the scale and toll of the pandemic.

India has officially recorded more than half a million deaths due to the novel coronavirus until now. It reported 481,000 Covid deaths between 1 January 2020 and 31 December 2021, but the WHO's estimates put the figure at nearly 10 times as many. They suggest India accounts for almost a third of Covid deaths globally.

So India is among the 20 countries - representing approximately 50% of the global population - that account for over 80% of the estimated global excess mortality for this period. Almost half of the deaths that until now had not been counted globally were in India.

Reuters

ReutersIts absence from global databases such as the World Mortality Dataset means that the only national numbers the country has are model-based estimates of all-cause excess deaths. (These models have looked at state-level civil registration data, a global burden of disease study, mortality reported by an independent private polling agency, and other Covid-related parameters.)

Earlier this week, the government released civil registration data showing 8.1 million deaths in 2020, a 6% rise over the previous year. Officials played it down, saying all the 474,806 excess deaths could not be attributed to Covid. According to official records, some 149,000 people died of Covid in India in 2020.

"Essentially, Indian death rates from Covid were not exceptionally low, only exceptionally undercounted," says Prabhat Jha, director of the Centre for Global Health Research in Toronto and a member of the expert working group supporting the WHO's excess death calculation

Three large peer-reviewed studies had found that India's deaths from the pandemic by September 2021 were "six to seven times higher than reported officially". A paper in The Lancet by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), an independent global health research centre, uses subnational all-cause mortality data from 12 Indian states. They come close to the WHO's estimation.

India has consistently rubbished the unflattering independent modelling estimates which many say fly in the face of the government's triumphalist narrative of combating Covid. Authorities have described them as "fallacious, ill-informed and mischievous in nature", and alleged that the methodologies and sampling sizes were flawed. The likelihood of under-reporting was minimal, they said.

"I fear that by now even if [all] the data is available, the government would be hesitant to make it public as it conflicts with their published [death] figure and the narrative that India beat Covid due to various reasons," Mr Karlinksy says.

To be sure, many countries have struggled to provide proper death tolls during the pandemic. Victims were excluded because they were not tested for the virus, and death registration has been patchy and slow. Also all-cause deaths data is published with a significant lag even in many developed countries.

India trails behind countries such as the US and Russia, where vital death registration is complete and published regularly. Death data has been a "bit obscure" in China - the only country comparable in population size to India - but authorities there have released some annual data on all-cause deaths for 2020 and 2021, according to Mr Karlinsky. Like India, Pakistan shared no data, despite having "supposedly good registration".

It's not easy counting the dead in India.

About half the total deaths occur at home, especially in villages. Poor record-keeping means that out of 10 million deaths every year - based on demographic studies and estimated by the UN - seven million do not have a medically certified cause of death and three million fatalities are simply not registered. Women are undercounted and registration is especially low in the poorest states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar.

But India, say researchers, also refuses to make basic pandemic data public - breakdown of cases, hospitalisations and deaths by age, sex and vaccination status. Without reliable data on death numbers, it becomes difficult to confirm whether the successful vaccination programme is, in fact, reducing deaths.

"Data paucity and data opacity have been the hallmarks of the pandemic in India, There is often an insular, nonchalant arrogance about not improving data quality or making data available," says Bhramar Mukherjee, a professor of biostatistics and epidemiology at the University of Michigan who has been closely tracking the pandemic.

Others find India's stubborn insistence on the veracity of its official pandemic toll baffling. Compensation claims for Covid deaths in some states exceed their official figures. "Political opposition across party lines is understandable, but that's not an excuse to fly blind," says Mr Jha, who also led India's ambitious Million Death Study.

Reuters

ReutersResearchers say India should improve the civil registration system, incentivise reporting of death, improve medical certification and data. India could also crowdsource deaths data through modern machine learning and community health workers, and from sources such as inactive biometric identity cards and cell phone records. As more and more deaths occur in hospitals - as in China - recording death registration and causes of death should become easier in the future.

One way India could get a fairly quick grip on the number of people who died of Covid would be to add a simple question to the forthcoming census: Was there a death in your household since 1 January 2020? If yes, please tell us the age and sex of the deceased and the date of death. "This would provide a direct estimate of excess deaths during the pandemic," Dr Jha says.

At the end of the day, information about death and disease is the key to improving health. In the 1930s, a big uptick in lung cancer death rates among men, recorded in routine data in the US and UK, led to identification of smoking as one of the major causes. In the 1980s, a surge in deaths among young gay men in San Francisco was picked up by the death registration system and led to the identification of HIV/Aids, marking the onset of a global epidemic.

Prof Mukherjee says India should silence its critics by releasing all-cause mortality data during the pandemic. "Counter science with science," she says. "Make all the national data available."