'I want to give my autistic son a voice'

BBC

BBCIt all started when Mugdha Kalra realised she didn't want to live in what she called an "autism village", an existence where she only interacted with children with special needs, their parents, therapists, and doctors.

That had been her life ever since her son, Madhav, was diagnosed with autism, a condition which affects how people communicate and interact with the world.

Madhav was three years old when his grandmother first noticed that he averted his gaze while talking. Slowly, he stopped talking much, choosing non-verbal cues instead.

His speech is need-based, his mother explained. "He'd say 'no' when he doesn't want to eat something, but many times he would choose to not speak at all," she said.

"Like he'd take my hand to his stomach when he is in pain and make a sound like 'aaooaa'. As a parent I had to develop an understanding of that."

Madhav would have several meltdowns in those early years. "He would cry uncontrollably," Ms Kalra said.

So, she started keeping a diary of the triggers, like too much noise or colour which would "lead to high levels of excitement". She also reached out to a community of parents with autistic children, which helped her find her feet. But she came to realise that she wanted much more for her son.

"The single most important thing in every parent's mind - what after we die?" she said. "I want this world to be as much mine and his as everybody else's. That's when I started taking him out, meeting people. That's the only way he can live his life."

But people had questions, especially children. Madhav is noticeably different and that, Ms Kalra said, could make others uncomfortable - "like when he is stimming (slang for self-stimulating behaviour which can include movements like rocking or head banging) - or repeats an action like rubbing his fingers against each other to calm himself down".

Madhav is 11 but his brain still works like that of a six-year-old, making him childlike. He doesn't speak much and likes to keep to himself.

He used to go to a school for children with special needs, but as learning shifted online due to the Covid pandemic, he struggled. So, his parents decided to opt for home-schooling.

There's still a lot of stigma around autism in Indian society, making it difficult for people with the condition to integrate with others. And a lack of awareness has perpetuated the neglect.

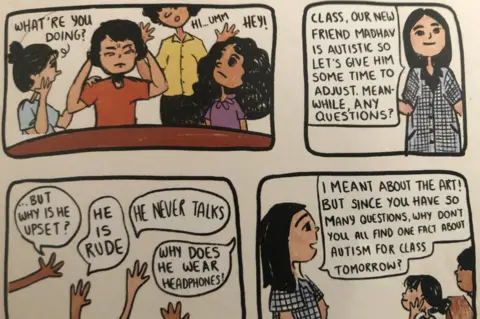

Madhav's cousins would ask Ms Kalra, why won't he play with them? Or why would he cover his ears with his hands? They called Madhav rude because he never made eye contact or listened to them, Ms Kalra said.

The questions were endless. So Ms Kalra decided to take a different approach to answering them: a comic book.

The comic, called Not That Different, imagines Madhav's journey going to a regular school instead of one for children with special needs.

"I was very clear that the neurodiverse character in the comic book had to be Madhav," Ms Kalra said. "Why hide him? Instead let's give his experience a voice. And without baring yourself, you won't find empathy. People would just not engage."

Neurodivergence - also known as neurodiversity - refers to the community of people who have dyslexia, dyspraxia, ADHD, are on the autism spectrum, or have other neurological differences.

Madhav's mind is too young to understand the comic, which is abstract, based on humour and a level of comprehension that he does not have, his mother said. His two teachers help him learn three-letter words, basic addition-subtraction and focus on life skills, like concepts of "what sinks, what dissolves" or identifying currency notes.

For the comic book, Ms Kalra collaborated with three women: Nidhi Mishra, founder of a global creative publishing platform called Bookosmia; Aayushi Yadav, a children's illustrator; and Archana Mohan, an award-winning children's author.

Aayushi Yadav said she had never spent time with a child like Madhav before this project.

Her illustrations are typically rooted in distinct forms of exaggeration. So, a laughing face would show all teeth out and even the back of the throat.

But drawing Madhav was a reverse experience, Ms Yadav said. It made her question the concept of what is widely understood as "a likeable character". She said she worried about making the child look "blank or rude".

Ms Kalra would send pictures of Madhav to the team, show them his room over Zoom calls, and share anecdotes that would form the basis of the comic book.

For instance, one of the comic strips explained how Madhav tends to shut his ears because he does not like loud sounds. This was something Ms Kalra learnt on her son's sixth birthday.

So, birthdays now mean getting his ceiling filled with helium balloons, having his favourite food - noodles - and perhaps a trip to the zoo with one or two friends.

But telling Madhav's story has not been easy.

Ms Kalra said her pitch was rejected multiple times. Several publishing houses did not want to take it up - they found the issue "too boring or not one most people would identify with". However, Ms Mishra was willing to take the chance.

Ms Kalra said that sharing her experiences of raising an autistic child has made her more perceptive. Besides the comic, she uses the internet - a blog, a YouTube channel, and her Instagram - to create discussions.

It has also helped her fight back against negativity, she said.

In 2019, Madhav had a seizure for the first time. His parents rushed him to hospital where he was stabilised after medication.

Madhav has been fine since, though the possibility of another attack lingers, Ms Kalra said.

It has taken time, but she has trained herself to live with the expectation of happiness and not fear, she said.

"That's why I am doing what I can to leave him in a world that is loving and understanding. Even if not loving, at least understand him, and let him be."