India's Covid crisis: The newsroom counting the uncounted deaths

Reuters

ReutersOn 1 April, the wife and daughter of an editor of a leading newspaper in India's western state of Gujarat went to a state-run hospital to get the daughter a Covid-19 test.

Waiting in the queue, they noticed two body bags on gurneys. Workers at the hospital in the capital, Gandhinagar, said the patients had died of Covid-19.

The mother and daughter returned home and told Rajesh Pathak, who edits a local edition of Sandesh, what they that had seen.

Mr Pathak called his reporters that evening and decided to investigate further. "After all, the government press statements were showing no Covid-19 deaths for Gandhinagar yet," he said. Only nine deaths from Covid-19 were officially recorded in Gujarat that day.

The next day a team of reporters began calling up hospitals treating Covid-19 patients in seven cities - Ahmedabad, Surat, Rajkot, Vadodara, Gandhinagar, Jamnagar and Bhavnagar - and kept a tab on deaths. Since then, Sandesh, a 98-year-old Gujarati language newspaper, has published a daily count of the dead, which is usually several times more than the official figure. "We have our sources in hospitals, and the government has not denied any of our reports. But we still needed first-hand confirmation," Mr Pathak says.

Sandesh

SandeshSo the newspaper decided to do some old-fashioned shoe-leather journalism. On the evening of 11 April, two reporters and a photographer staked out the mortuary of the 1,200-bed state-run Covid-19 hospital in Ahmedabad. Over 17 hours, they counted 69 body bags coming out of a single exit before they were loaded into waiting ambulances. Next day, Gujarat officially counted 55 deaths, including 20 from Ahmedabad.

On the night of 16 April, the journalists drove 150km (93 miles) around Ahmedabad and visited 21 cremation grounds. There they counted body bags and pyres, examined registers, spoke to cremation workers, looked at "slips" which assigned the cause of death, and took photographs and recorded videos. They found that most of the deaths were attributed to "illness", although the bodies were being handled under rigorous protocols. At the end of the night the team had counted more than 200 bodies. But the next day, Ahmedabad counted only 25 deaths.

All of April, Sandesh's intrepid reporters have diligently counted the dead in seven cities. On 21 April, they counted 753 deaths, the highest single-day tally since the deadly second wave washed over the western state. On a number of other days, they counted in excess of 500 deaths. On 5 May, the paper counted 83 deaths in Vadodara. The official figure was 13.

Hitesh Rathod/Sandesh

Hitesh Rathod/SandeshThe Gujarat government denies under-counting and says it is following federal protocols.

But reportage by other newspapers has stood up the alleged under-counting. The English language Hindu newspaper, for example, reported it had information that 689 bodies were cremated or buried in the seven cities following Covid-19 protocols on 16 April, when the official death toll for the entire state was 94. Some experts reckoned that last month alone Gujarat might have under-counted Covid-19 deaths by a staggering factor of 10.

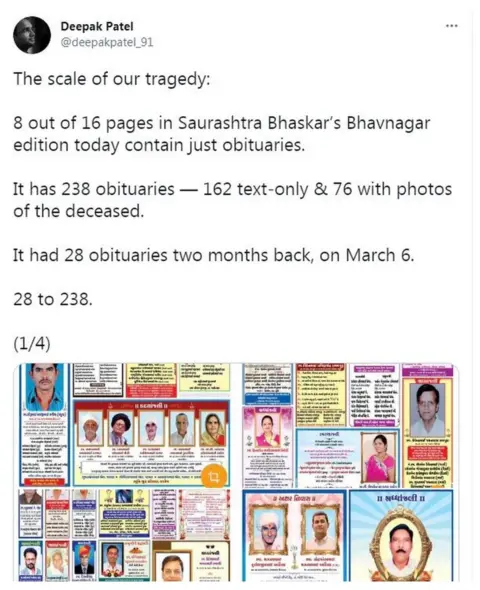

With the pandemic forcing people to stay away from the rituals of grief, newspapers were overflowing with obituaries.

And some of the obituaries appeared to point to the under-counting that was taking place:

Twitter

Twitter

The number of funerals at a cremation ground in Bharuch district on Saturday also did not tally with the official death statistic, according to this report in Gujarat Samachar, another leading local newspaper:

Twitter

Twitter

Gujarat has so far officially registered more than 680,000 Covid-19 infections and over 8,500 deaths. Under-counting of deaths have been reported from several Indian cities badly hit by the pandemic. But the scale of Gujarat's under-counting appears to be massive, and has even provoked the state's high court to admonish the state government, run by Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ruling BJP. "The state had nothing to gain by hiding the real picture and hence suppression and concealment of accurate data would generate more serious problems including fear, loss of trust, panic among the public at large," the judges said in April.

Many believe that most Covid-19 deaths are being attributed to the patient's underlying conditions or co-morbidities. A senior bureaucrat, who preferred to remain unnamed, told me only patients testing positive for the virus and dying of "viral pneumonia" were being counted as Covid-19 deaths. Chief minister Vijay Rupani says "every death is being investigated and recorded by a death audit committee".

To be sure, counting bodies at mortuaries or cremation grounds and tallying them with official figures for the day can be imprecise as official statistics come with a time lag, according to Prabhat Jha of the University of Toronto, who led India's ambitious Million Death Study. Countries such as UK have reduced the official death toll from coronavirus after a review of how deaths are counted. Covid-19 deaths have been under-reported by as much as 30 to 40% worldwide, studies have shown.

Reuters

Reuters"Reporting and recording systems are swamped during a pandemic, so officials often take time to update [numbers]. But update they must, and record all the deaths. Counting body bags at hospitals and cremation grounds is a good way to put pressure on authorities to come clean," Dr Jha says.

For the journalists, it has been a harrowing experience.

Hitesh Rathod, a photographer at Sandesh, recounted the harrowing experience of counting the dead. "People were getting admitted and coming out as body bags," he said. He found six-hour-long queues of bodies at crematoria, which he says reminded him of the "long queues of people outside banks after demonetisation," Mr Modi's controversial 2016 ban on high denomination currency.

"Five years later, I found similar queues outside hospitals, mortuaries and cremation grounds. This time there were queues of the people struggling to stay alive and queues of the dead," he said.

Ronak Shah, one of Sandesh's reporters, says he was shaken up by the wails of three young children piercing the still night when the hospital's PA system announced the death of their father. "The children were saying they had come to the hospital to pick up their father and go home. They returned with his corpse seven hours later," Mr Shah says.

Dipak Mashla, who led the team to the cremation grounds, says he returned home "scared and shaken". "I saw parents come with body bags of their dead children, pay money to the funeral worker and tell them, 'Please take my child and burn him'. They were too scared to even touch the corpse."

Imtiyaz Ujjainwala, another reporter on the team, believes the scale of under-counting has been considerably more, considering he and his colleagues only counted bodies from one hospital. There were more than 171 private hospitals treating Covid-19 patients in Ahmedabad, he said. "And nobody is counting there."

Read more of our Covid coverage