India's Covid crisis: Your questions answered

Reuters

ReutersIndia has had more Covid-19 cases in the last seven days than anywhere else in the world. Experts believe the real death toll may be higher than the official numbers.

Many of you have been sending us questions regarding the current situation and we asked experts inside and outside the BBC to answer them.

Why is India's second wave devastating? Jabran Ali Khan

Dr Om Srivastava, consultant and visiting professor, infectious diseases, Mumbai, answers: We were very careful in the first wave. The story of the Dharavi slum in Mumbai is a fantastic example of how infections can be contained. It was a model replicated across the world.Over a period of time, from about November of last year, we probably became a little bit complacent, thinking it was out of our lives.

In doing that, we probably did not keep the social distancing we should have. And then there were a number of events after that where social distancing was not possible - election campaigns and the Kumbh Mela.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThat kind of situation, where we don't keep social distancing, will usually keep coming back to hurt you. There are other reasons. If you look at second waves historically, they've always been more aggressive and bigger in number than the first. The intensity this time round, though, is more about the overbearing requirement for people to have two things. Firstly, the need to get into a hospital and have a bed with oxygen where they can feel a bit secure. And secondly, the amount of anxiety that comes from not getting a bed.

That has been the overwhelming sentiment of most people who may or may not need hospitalisation, but feel it is the most secure place for them.

Does India have enough medical infrastructure for its vast population? Ealias in Singapore

Yogita Limaye, BBC India correspondent, answers: In 2018, India's spending on healthcare was 1.28% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP). By comparison, in the US it was 17%.

From numbers published by the Indian government in 2019-20, there is one doctor per 1,456 people in the country.

This underinvestment in public healthcare is a long-running issue. Successive governments have not made it a priority.

In smaller cities, towns and rural areas, the situation is particularly bad. Hospitals have inadequate equipment and staff. In some parts of the country, people have to travel miles to get to any kind of medical services.

Reuters

ReutersHow is the Indian government addressing the crisis? Sri in US

Yogita Limaye, BBC India correspondent, answers:Prime Minister Narendra Modi said he held three meetings on Tuesday to discuss ways to scale up oxygen capacities and medical infrastructure. Trains and military aircraft are being pressed into action to speed up the transport of oxygen supplies.

But on the ground, this is not reaching people in desperate need.

In Delhi, there are centralised helpline numbers which people have been asked to call if they need a hospital bed. But in reality, it is next to impossible to get one in the city because facilities are so overrun.

People are angry. When we've met families of Covid patients, they've been asking: "Where is the government? What is it doing?"

Many are asking why the military and disaster response teams have not been pulled in to build field hospitals on a war footing.

There is a sense of abandonment in the country, of people being left to fend for themselves.

With about a billion people in India, shouldn't their daily deaths total be much lower per population than in the UK? Mike

James Gallagher, BBC health and science correspondent, answers:The population of India is in excess of one billion. However, there are many other factors to think about when comparing the two countries.

One is the capacity of the healthcare system - parts of India's are being overwhelmed in a way the UK's health service never was. There is thought to be significant underreporting of infections in India, and there is also a massive difference in trajectory.

The number of cases has fallen by 97% in the UK since the peak in January, while cases are still climbing sharply in India. The people who are dying in India today were infected weeks ago and the huge surge in the virus since then is likely to lead to a similar surge in deaths.

How can we help from the UK? Kate in UK

Sima Kotecha, Newsnight correspondent, BBC News, answers: The depth of feeling among people of South Asian heritage here is inescapable. Watching the constant stream of horrific pictures coming out of what some describe as their motherland has been heart-breaking and draining.

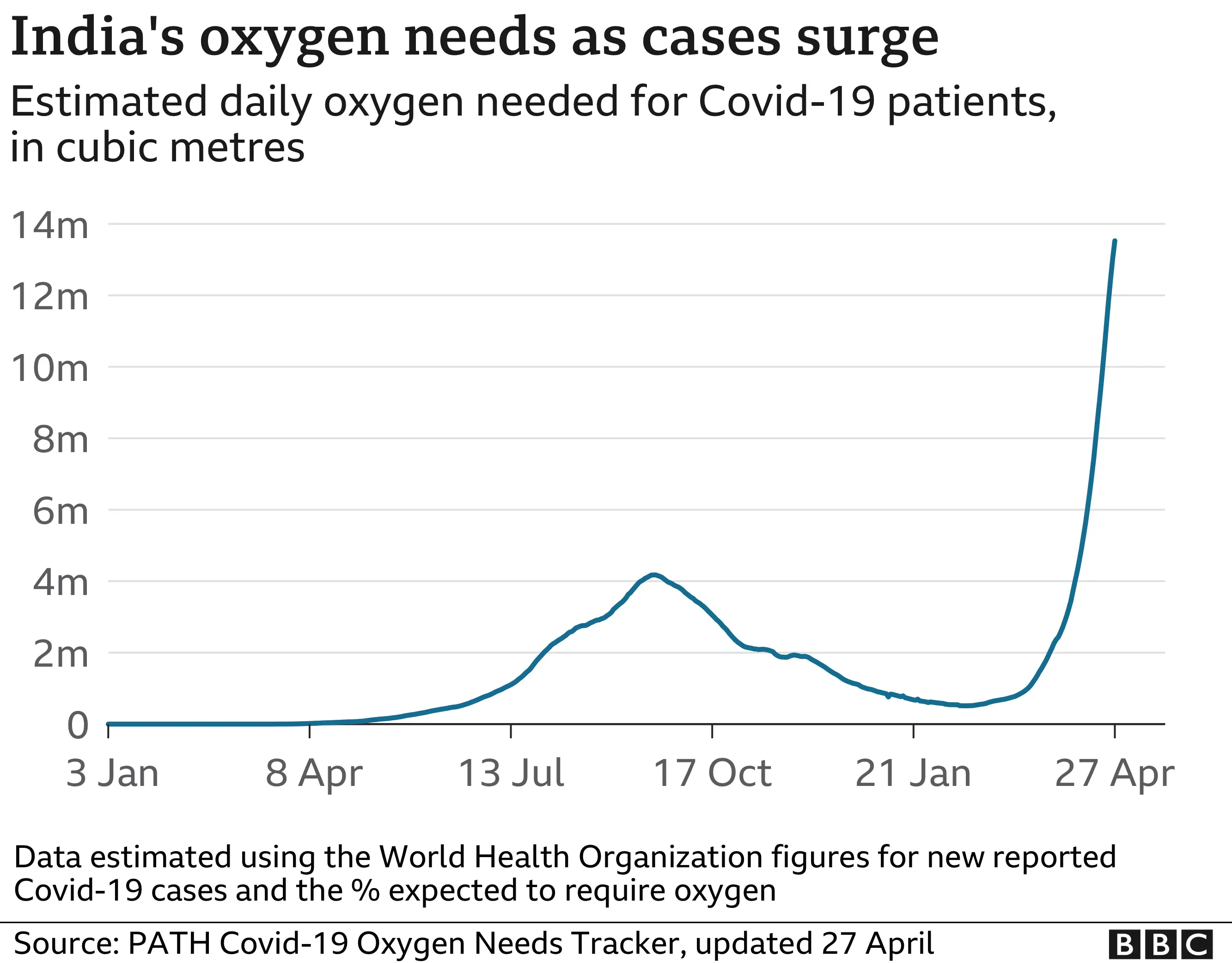

Many are desperate to help, so various UK charities have set up donation pages to raise money for oxygen concentrators as the country grapples with a severe shortage.

British Indian doctors tell us they're providing advice and support to healthcare officials on the phone, with some arguing they're more experienced in Covid after dealing with several surges of the virus over here.

Temples are also hosting special prayers for India to provide Hindu worshippers with a place to go and think about their loved ones. One Indian woman who has parents in Delhi told us: "I have little money, so all I can do is pray."

IDREES MOHAMMED/EPA

IDREES MOHAMMED/EPAWhy can't India apply the same method of producing oxygen that some places in Africa use, even when they have no electricity? G. Doyle

Dr Om Srivastava, consultant and visiting professor, infectious diseases, Mumbai, answers: We tend to think of our oxygen needs in these terms: two or three litres of oxygen delivered through a nasal prong.

When you have people who are in ICU, or even a step down from that, they sometimes require high flow nasal cannulas and between 10 and 40 litres of oxygen.When you have hospitals that become Covid hospitals, the total consumption of oxygen is far more than you would normally expect.

You will do the right thing by asking for more oxygen or preparing for future patients - but these processes take time, no matter what the modes of production.

When you have an overwhelming situation and the need is so high, there will be disparity between what is available and what can be delivered. Oxygen is something that needs to be looked at, calculated and prepared for - just like every other resource. It has to be done in particular time so you can provide needs for all patients who come to you.

But there is a lot of media focus on oxygen when there is also a clear requirement for nurses, ward attendants, doctors and medical staff; I see that in every walk of life, not just hospitals but also in community centres and primary health care centres.

How far has India been able to immunise its citizens? Moses Bomboka, Uganda

Reuters

ReutersYogita Limaye, BBC India correspondent, answers:India has administered just under 150 million doses of vaccine. Some people have had two doses, but most of those vaccinated so far have had one dose.

India has a population of 1.3 billion. So it needs hundreds of millions of doses of vaccine to cover a significant part of its population.

So far vaccines are available to those over the age of 45. From 1 May, they will be available to everyone over 18 years of age. But it's unclear what stock of vaccines India currently has, and how quickly it will be able to vaccinate people.

What are the political implications for the Modi government over its handling of this crisis? Poorvika, London

Vikas Pandey, India editor, BBC News website, answers:It is too early to judge the political implications for the Modi government or the state governments. But one thing that is clear is there is a lot of anger among people as the second wave is ripping through small towns and villages.

The desperate cries for help are not just coming from Delhi and Mumbai, but from remote corners of the country including Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan.

There is a lot of anger against politicians and the system, including bureaucrats, officials and health officials.

EPA

EPAWhat is the situation like in the state of Punjab? B Singh, Yorkshire, UK

Sarbjit Singh Dhaliwal, BBC Punjabi service, answers:Punjab's health minister Balbir Singh Sidhu told the BBC the situation in rural areas is worse than urban areas.

He said: "In rural areas people are reluctant to go to hospitals and only serious patients come to hospitals.

"Mostly, people ignore the initial symptoms and reach out for healthcare when their situation deteriorates."

If India prioritises using its vaccines domestically over exporting them, will that affect the UK's inoculation process? Adam, UK

James Gallagher, BBC health and science correspondent answers: It is unlikely to have a major impact, because the UK has massively overbought vaccines to the tune of 500 million doses.

While only three types are currently being used, the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines would not be affected by the situation in India.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is being made by the Serum Institute in India, but that vaccine is also being made in the UK and on continental Europe.

Is the Covid 19 strain different in India and the UK, and why are so many dying so quickly? Joan, UK

James Gallagher, BBC health and science correspondent, answers:One reason people are dying in India is the number of cases has overwhelmed the ability of some hospitals to treat them.

Covid is deadly even with the best care, but when there are not enough doctors or oxygen to go round, then people die who would survived if they were treated. Variants may be playing a role, but there is still relatively little detail.

The B117 variant (that's the one that was first detected in the UK) is able to spread more quickly and is in India. There is also a new variant (B1617), which was first detected in India in October. However, exactly how widespread it is, and how big a role it may be playing in the surge is cases, is still being investigated.

How much longer can the supply of dry wood for cremations last? Surely burials will be needed or are these not accepted on religious grounds. Anon, New Zealand

Vikas Pandey, India editor, BBC News website, answers:We haven't heard about the shortage of dry wood for cremations at the moment. And that is not really difficult to procure. So we haven't seen a shortage of wood fire, but shortages of space.

Now cremations are happening in parking lots of funeral grounds and in public parks.

The burial grounds used by the minority Muslim community are also full.

Produced by, Georgina Rannard, Dhruti Shah and Kris Bramwell