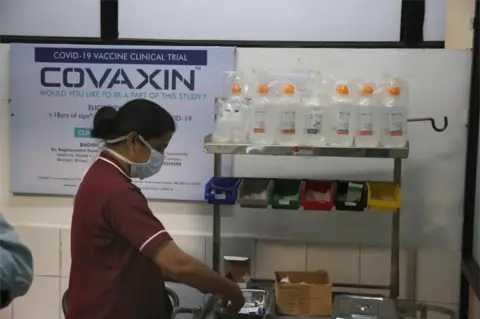

Covaxin: What was the rush to approve India's homegrown vaccine?

Reuters

ReutersHow can a coronavirus vaccine be cleared for emergency use by millions of vulnerable people in a "clinical trial" mode?

No idea, says Dr Gagandeep Kang, one of India's best-known vaccine experts. "Either you are doing a clinical trial or not". Clinical trials - a three-phased process - determine whether the vaccine induces good immune responses and whether it causes any unacceptable side-effects.

On Sunday, India's drug regulator gave emergency approval of a locally produced coronavirus vaccine, called Covaxin, before the completion of trials. The government-backed vaccine has been developed by Bharat Biotech, a 24-year-old vaccine maker, which has a portfolio of 16 vaccines and exports to 123 countries.

The regulator said the vaccine had been approved for "restricted use in emergency situation in public interest as an abundant precaution, in clinical trial mode, especially in the context of infection by mutant strains". (The regulator also approved the global AstraZeneca Oxford jab, which is also being produced in India.)

This, despite the fact that the key third phase of Covaxin's clinical trials - the vaccine is given to thousands of people and tested for efficacy and safety - was underway.

Reuters

ReutersAssurances by the regulator that the vaccine is "safe and provides a robust immune response" have not placated most scientists and health experts. All India Drug Action Network, a watchdog, said it was "baffled to understand the scientific logic" to approve "an incompletely studied vaccine".

Bharat Biotech says it has a stockpile of 20 million doses of Covaxin, and is aiming to make 700 million doses out of its four facilities in two cities by the end of the year. "Our vaccine is 200% safe," says Dr Krishna Ella, chairman of the firm.

Dr Ella has defended the approval. For one, he said, Indian clinical trial laws allowed "accelerated" authorisation for use of drugs after the second phase of trials for "unmet medical needs of serious and life-threatening diseases in the country". The fact that his vaccine was based on an inactivated form of coronavirus - a reliable and time-tested platform - also helped.

Studies on monkeys and hamsters had shown that Covaxin provided ample protection against the infection, Dr Ella said. Nearly 24,000 of the 26,000 volunteers had already participated in the ongoing third phase trials, and the firm was expected to have the efficacy data for the vaccine by February, he added.

Scientists are sceptical. "Since there is no data for the third phase of trials, we don't know how efficacious this vaccine is. We know it is safe, going by the limited phase two trials. What if we roll out a vaccine with unknown efficacy and later find it to be only 50% efficacious? Would it be fair to people who received it?" Dr Shahid Jameel, a leading virologist, told me.

It is still not clear what the regulator meant by saying that the vaccine would be administered in a "clinical trial mode". In a conventional trial, volunteers are not told whether they are given the vaccine or a placebo, and many are excluded from participating because of pre-existing health conditions.

Dr Ella said his firm will monitor the recipients after they've taken Covaxin jabs. This is likely to add to the logistics of the vaccination programme.

EPA

EPASo did the regulator actually mean Covaxin would be administered to people in a "fourth phase of clinical trials" for ongoing studies after the vaccine is approved and marketed? "Give us some time to understand the whole thing. We don't know whether this will be treated as a trial," Dr Ella said.

That's not all.

A senior member of the federal Covid-19 taskforce muddied the waters further by saying that Covaxin would be "like a back-up [vaccine]" in the event of a sharp spike in cases. Epidemiologists I spoke to say they are baffled. "Does it mean that in the event of a surge, some people will be given a vaccine of unproven efficacy?" a senior epidemiologist said.

However, Prof Paul Griffin, an expert in infectious diseases at the University of Queensland, says it is not unheard of vaccines to be used in emergency circumstances in a targeted way whilst still under a clinical trial framework. This is usually considered if the ongoing trials are robust and if the data from earlier trials supports the vaccine's expanded use "both in terms of safety as well as efficacy", he told me.

With more than 10 million coronavirus infections, India has the second highest number of reported cases after the US. The pandemic has battered its economy. India plans to vaccinate some 300 million people between January and July. But the rollout is also happening at a time when cases have slowed down considerably. Bharat Biotech is a well-known vaccine maker, with a track record of clinical trials in 20 countries, involving more than 700,000 volunteers.

So why could India not wait for a few weeks more for the final trials to be over and approved a vaccine of proven efficacy? Why this haste?

Getty Images

Getty Images"It is incomprehensible," Shashi Tharoor, a senior opposition politician and MP, told me.

Mr Tharoor blames this "unseemly haste" on Narendra Modi's BJP government "which enjoys placing slogans over substance". In this case, he says, "chest-thumping 'vaccine nationalism' - combined with the PM's "self-reliant India" campaigning - trumped common sense and a generation of established scientific protocols". Others say "poor science communication" and a lack of transparency by regulatory officials had also contributed to this fiasco.

India is a vaccine-making powerhouse, making 60% of the world's vaccines. It runs the world's largest immunisation programme targeting 55 million people - mainly newborns and pregnant women - who receive some 390 million free doses of vaccines against a dozen diseases every year.

The Covaxin fiasco holds many lessons for India.

As the virus devises ways to grow more infectious, a number of vaccines may be needed to counter it and prevent severe disease among infected people.

"Approval for all vaccines must be provided on the basis of adequate evidence of efficacy and safety. Clarity on tested and approved doses and dosing schedules too is needed in that context," K Srinath Reddy, president of the Public Health Foundation of India, told me.

"It is in the interest of science and public confidence that all concerns related to any vaccine are adequately addressed. We cannot win this battle if we doubt the weapons that are being handed to us," he added.