Coronavirus: India home quarantine families face discrimination

BBC

BBCIndia has quarantined tens of thousands of people in their homes. But some of the measures designed to keep them inside - like the signs posted outside their houses and releasing their personal data - have led to unintended, and unpleasant, consequences. The BBC's Vikas Pandey reports.

Bharat Dhingra's family of six have been in "home quarantine" in India's capital, Delhi, since his brother and sister-in-law returned from the US on 22 March.

Neither have displayed any symptoms, but the entire family followed government advice and self-quarantined.

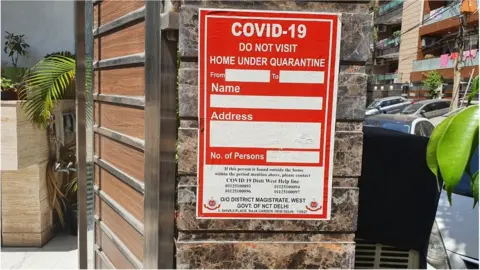

Then officials posted a sticker outside their houses that read: "Do not visit. Home under quarantine".

It was supposed to ensure people abided by the rules. But for people like Mr Dhingra - who was already diligently following the rules - the sign has caused "stress and psychological pressure".

"Our house has become like a zoo," he told the BBC. "People stop to take pictures when they pass by. Our neighbours tell us to go inside even when we step out into our balcony for a minute.

Getty Images

Getty Images"We also understand that the houses that are in quarantine need to be marked for awareness," he acknowledged. "Government officials have been very nice to us, but it's the attitude of some people that hurts.

"Some people shared the picture of our house in local WhatsApp groups as a warning."

He said it violated his family's privacy.

"People need to realise that home quarantine is a precautionary measure - it doesn't mean we are infected, but let's say even if we are, we don't need to be ostracised for it."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe BBC spoke to several people across the country who have had similar experiences.

One couple, who did not wish to be identified, said that their home in Noida - a suburb of Delhi - had become "a place of horror for many".

"We went into home quarantine straight after coming back from abroad as a precautionary measure. Little did we realise that we will be completely shunned by the community."

What they'd like is just some words of encouragement on the phone or a text message.

"But everybody looks at us with suspicion - even when we are on our balcony. It's in their eyes.

"We're not meeting anybody. It's really sad that we are being treated like this."

Kulpreet Singh also faced similar issues when he was told to quarantine himself at his home in Farrukhabad district, in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh.

He had met Bollywood singer Kanika Kapoor, who later tested positive, at a party.

Getty Images

Getty Images"The case was discussed endlessly in the media and that put so much pressure on my family," he said. "All kinds of rumours started spreading. Some said I was vomiting blood and will die in a few days."

Mr Singh said that "people are scared and they believe any rumour on social media".

His quarantine period has now ended but, he says, the stigma will take a long time to go.

"Even vegetable and milk vendors refuse to come to deliver to our house."

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: How do I protect myself?

- AVOIDING CONTACT: The rules on self-isolation and exercise

- MAPS AND CHARTS: Visual guide to the outbreak

- VIDEO: The 20-second hand wash

- STRESS: How to look after your mental health

In some cases, the way testing was conducted also caused problems: one couple in the eastern state of Bihar said that their son was told to come out of their apartment building and into the street to give his swab for testing.

"He was in home quarantine after returning from Canada. Seeing so many doctors in hazmat suits made our neighbours really scared. People stopped saying hello - even from a safe distance."

They added that their son tested negative, but the discrimination continues.

"People are still reluctant to interact with us," they said.

Data leaked

Meanwhile, the names and addresses of those in quarantine were made public in the southern cities of Hyderabad and Bangalore.

"People [in home quarantine] were happily moving around as if they are on a holiday and that is why the data was shared,'' a senior officer in Bangalore explained to BBC Hindi's Imran Qureshi.

But experts say this violates people's privacy.

"It would have been fine if the government had only published the name. But giving addresses is an invitation for trouble," Bangalore-based lawyer KV Dhananjay said.

Some protests over quarantine facilities have also been reported. In Mysore, 150km (93 miles) from Bangalore, locals forced authorities to evacuate a hotel where 27 people were quarantined.

Hindustan Times

Hindustan Times"People feared that those staying in the hotel would spit from the window and they would catch the infection," said MJ Ravikumar, who lives in the area and is a former deputy mayor of Mysore.

Senior police official CB Ryshyanth said strict action would be taken against those who discriminate and spread rumours.

Meanwhile, the personal data of at least 19 people quarantined at home - including their telephone numbers - was also leaked in Hyderabad.

This resulted in phone calls at odd hours and unwanted advice on "how to kill the virus" for some of the families.

Ramesh Tunga, who left the city a day before the lockdown was announced on 24 March, said he was facing similar discrimination.

"I left Hyderabad to be in my village. I informed village officials and went into self-isolation even though I had no overseas travel history," he said.

But it caused "more problems for me".

"People stopped talking to my family. Everybody just believed that I had coronavirus and I was going to infect the whole village," he said.

"Being careful is good but people shouldn't stop being human."