India election 2019: The man who has lost 24 times but won't give up

Omkar Khandekar

Omkar KhandekarEvery Indian election throws up several independent candidates who, despite the odds stacked against them, take a chance on democracy. Omkar Khandekar reports on one man who has lost two dozen times but refuses to stop trying.

Vijayprakash Kondekar is now a familiar face in Shivaji Nagar in the western city of Pune.

For the past two months the 73-year-old has been going around the neighbourhood trying to drum up support for his election campaign.

"I just want to show people that party politics is not the only way in the largest democracy in the world," he says. "I plan to give the country independent candidates like myself. It's the only way we can clean up all the corruption."

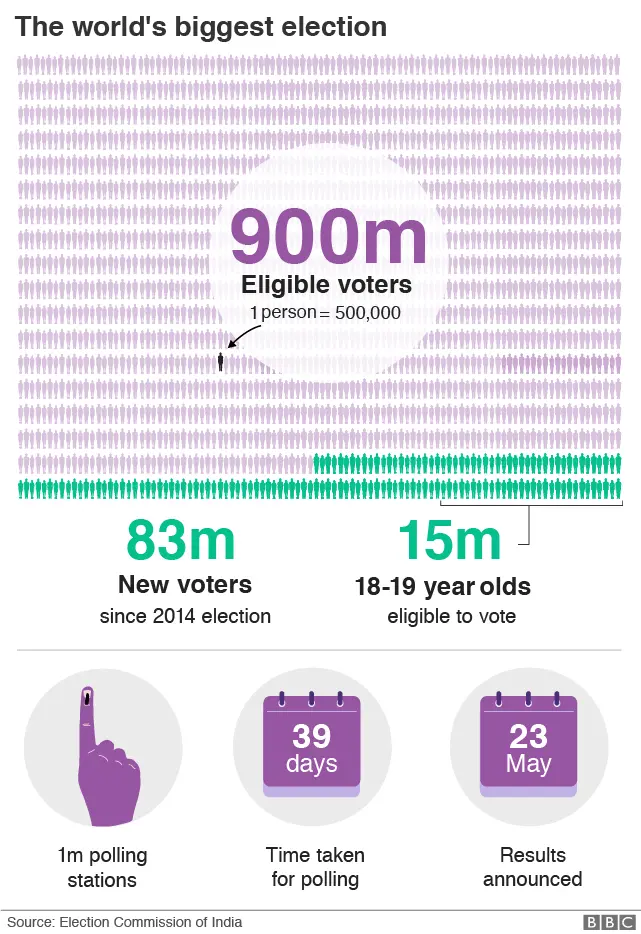

Mr Kondekar is contesting a parliamentary seat that will go to the polls in the third phase of voting on 23 April. India's mammoth general election kicked off on 11 April and is taking place over seven stages, with votes being counted on 23 May.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMr Kondekar is running as an independent candidate. One day, he hopes to become prime minister.

If that happens, he says he will give every Indian citizen 17,000 rupees ($245; £190). He says doing so would be "easy enough" if the government reduced other expenses.

Until the late 1980s, he used to work for the state electricity board in Maharashtra. Now, he can often been seen walking around Pune, pushing a steel cart on wheels with a signboard attached to it. Previously, locals say, the board carried a request for donations - but not much, less than a dollar.

Now the signboard says "Victory for the boot" - a reference to the election symbol allotted to Mr Kondekar by India's Election Commission.

It makes for an amusing sight in the city's streets. While many people ignore the aspiring politician, others request selfies. Mr Kondekar happily obliges, hoping to benefit from free publicity on social media.

Omkar Khandekar

Omkar KhandekarOthers openly scoff at what they see: a frail man with long white hair and a beard, walking in the hot April sun to canvass for votes while wearing only cotton shorts.

And that's before they find out that Mr Kondekar has contested - and lost - more than 24 different elections at every level of the Indian political system, from local polls for municipal bodies to parliamentary elections.

He is one among hundreds of independent candidates trying their luck in this year's national election. In 2014, just three of the 3,000 independent candidates who contested won.

Read more about the Indian election

Although there is precedent for independent candidates to succeed en masse - in the 1957 election, 42 of them were elected as MPs - it very rarely happens. Since the first election in 1952, a total of 44,962 independent candidates have run for parliament, but only 222 have won.

Independents rarely win because parties have far more money and better resources available to them. And there's no shortage of parties, with 2,293 registered political parties, including seven national and 59 regional parties.

The governing Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and opposition Congress are the two major national parties but in many states they trail strong regional parties with hugely popular leaders.

But Mr Kondekar says he has found a novel strategy to gain an advantage.

As per election rules, candidates from the national parties are listed first, followed by those from state parties. At the bottom are the independents. "My appeal [to the public] is vote for the last candidate, the one listed before the none-of-the-above option. In all probability, it will be an independent candidate," he says.

For Tuesday's vote, he has changed his surname to Znyosho, so that his name appears last on the candidate list.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDespite the disadvantages they face, independent candidates jump into the fray every election for myriad reasons. For some it's a vanity project, while many are fielded by political parties hoping to divide votes.

Others, like K Padmarajan, contest the polls as a stunt. He has taken part in - and lost - more than 170 elections only to earn a place in the Guinness Book of World Records.

Mr Padmarajan, who is competing against Congress leader Rahul Gandhi in the southern seat of Wayanad this Tuesday - recently said, "If I win, I will get a heart attack."

Such candidates have even prompted India's law commission to recommend a ban on independent candidates contesting state or national parliamentary elections.

That never happened. And although more and more independents are taking part, their success rate is not increasing.

"Political parties have a stranglehold on the Indian political system," says Jagdeep Chhokar, founder of election watchdog the Association for Democratic Reforms.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are several systemic problems stymieing independent candidates' election campaigns, Mr Chhokar adds. For one, there are limits on how much can spent by individual candidates but not the political parties backing them. Independent candidates also don't enjoy the income tax exemptions that political parties do.

"There are candidates who genuinely want to make a difference but funding limitations, lack of influence and public perception in favour of big parties often constrains their chances."

Mr Kondekar is aware that he's unlikely to win. Over the years, he has sold ancestral land and a house to raise money for his campaigns. His only source of income - as per the disclosures he made while filing his nomination - is a monthly pension of 1,921 rupees ($28; £21).

But while admitting that his fight is mostly symbolic, Mr Kondekar refuses to give up hope.

"It's a contest between their [political parties'] iron sword and my paper cut-out," he says. "But I want to keep trying. Given my age, this will most likely be my last election. But perhaps things might be different this time."