The Indian restaurants that serve only half a glass of water

BBC

BBCWhile many parts of India are going through a sustained water crisis, the western city of Pune is trying to deal with the problem in a rather unusual way, writes the BBC's Geeta Pandey.

The dystopian future we worried about is already here.

Many restaurants in the city of Pune have begun serving only half glasses of water to guests.

At the pure vegetarian Kalinga restaurant, a couple have just been seated when a waiter approaches their table and asks if they want water.

"I said yes and he gave me half a glass of water," says Gauripuja Mangeshkar. "I was wondering if I was being singled out, but then I saw that he had only poured half a glass for my husband too."

For a moment, Ms Mangeshkar did wonder whether her glass was half full or half empty, but the reason why she was served less water was not really existential.

Nearly 400 restaurants in Pune have adopted this measure to reduce water use, ever since the civic authorities announced cuts in supply a month ago.

Pune Restaurant and Hoteliers' Association president Ganesh Shetty, who owns Kalinga, told the BBC that they have worked out an extensive plan to save water.

"We serve only half glasses of water and we don't refill unless asked, the leftover water is recycled and used for watering plants and cleaning the floor," Mr Shetty explained. "Many places have put in new toilets which use less water, we have put in water harvesting plants and the staff are briefed on minimising water use."

Kalinga gets about 800 customers a day and by serving only half glasses, he says the restaurant is able to save nearly 800 litres (1,400 pints) of water a day.

"Every drop is precious and we have to act now if we want to save the future."

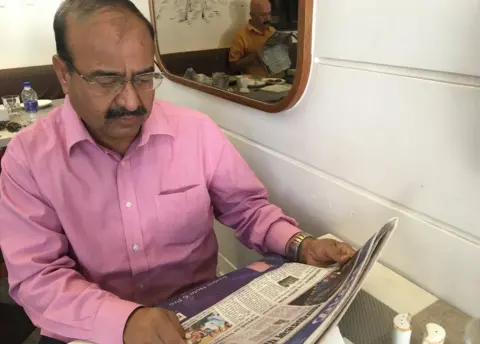

Owner of 83-year-old Poona Guest House, Kishor Sarpotdar, shows the shorter steel tumblers he's bought to replace the earlier taller ones. His restaurant is not only serving half glasses of water, he says, they are serving them in smaller ones too.

Pune is next door to India's financial capital, Mumbai. An educational and cultural hub, it was famously described as the "Oxford and Cambridge of India" by India's first prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru.

This city of four million people has been well served by the Khadakwasala dam built in 1878, and water shortages are new here.

Mr Shetty says the first major water crisis the city faced was two years ago.

"For two months in February and March, our water supply was reduced by half. We got water once in two days."

Strict guidelines were issued about what fresh water supplied by the civic authorities could - or couldn't - be used for. And people were encouraged to install bore wells to pump out ground water to meet additional requirements.

All construction in the city was stopped for two months, car garages were allowed to do only dry servicing, the city celebrated a dry Holi, clubs and water resorts were barred from holding popular rain dance events and swimming pools were ordered shut.

All misuse was checked and those who erred were made to pay hefty fines.

"It was very serious," says Col Shashikant Dalvi, Pune-based water conservation expert.

This year, he says, the situation is "worse". "Panic buttons have been pressed in October itself. How will we face the challenge in the summer months?" he asks.

According to a government report earlier this year, India is facing its worst-ever water crisis, with some 600 million people affected. The report said the crisis was "only going to get worse" in the coming years and warned that 21 cities were likely to run out of groundwater by 2020.

In May, the popular Indian tourist town of Shimla ran out of water, while last year it was reported that the city of Bangalore was drying up.

Large parts of the western state of Maharashtra, where Pune is located, are water deficient and every year, at the onset of the summer season, the state makes the news for "water wars" between districts - farmers, villagers, city residents, slum dwellers, the hospitality industry and businesses all clamouring for their share of water.

This year, that talk has already started. And it's just the beginning of winter. Many areas are already staring at drought and acute water distress.

And this time, Pune too is affected. In October, the Pune Municipal Corporation announced 10% cuts in supply for everyone.

Col Dalvi though is baffled about this shortage.

"The crisis two years ago," he says, "was because of deficient rainfall. But this year, Pune had excessive rainfall until the end of July. The dams were full. So where has the water gone?"

The monsoon rains will not come before June and eight months can be a long time. "It'll be a nightmare for the city unless we get some rains in the winter," he says.

Experts blame climate change, deforestation and the rapidly growing city population as the main reasons for the water shortage. And the fact that the Khadakwasala dam reservoir has never been de-silted, which means its capacity to hold water is reducing daily.

Col Dalvi offers a prescription to deal with the water shortage in Pune and the rest of the country, because by "2025 India will be most populous country in the world".

"Leakages must be plugged, unsustainable over-extraction of ground water must stop, rooftop rain water harvesting and recycling of water must be made mandatory, otherwise shortages would get more critical," he says.

What about restaurants serving half glasses of water to patrons? Is it just a gimmick, I ask.

"Not at all," he says. "It's not a gimmick. It's an excellent idea. A drop saved is a drop gained."