India activist arrests: Is this a political witch hunt?

Press Trust of India

Press Trust of IndiaBorn in Massachusetts, Sudha Bharadwaj gave up her American passport after her parents returned to India. She would eventually become a committed activist and trade unionist steadfastly fighting for the rights of the dispossessed in the mineral-rich state of Chhattisgarh, where some of India's poorest and most exploited live.

As a professor of law at a leading university, the 56-year-old taught about tribal and land rights and endeared herself to students. But it was her three-decade-long work among the poor in Chhattisgarh that made her a shining beacon of hope for many in the fight for justice. "It's ok that I will make some enemies in the process," she told a journalist in 2015. "But the struggle will go on."

One of the enemies she appears to have made is Prime Minister Narendra Modi's ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). On Tuesday, she and four other activists and lawyers were arrested from different cities for what the police say is their role in an incident of caste-based violence and their alleged links with Maoists, who, according to a former prime minister, pose India's "greatest internal security challenge".

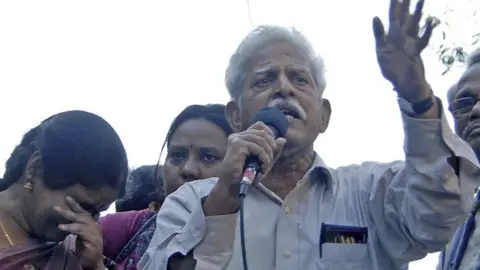

Tuesday's raids saw a group of activists and intellectuals arrested.

Seventy-eight-year-old Varavara Rao is a highly regarded writer, communist and a sympathiser of India's Maoists, who say they are fighting for communist rule and greater rights for tribal people and the rural poor. Gautam Navlakha is a civil liberties activist who was a member of the editorial board of a renowned academic journal.

Arun Ferreira and Vernon Gonsalves are Mumbai-based activists. In March, they jointly wrote an article for news website, The Wire, denouncing a controversial Indian law which, they said, "introduces a vague definition of terrorism to encompass a wide range of non-violent political activity, including political protest".

Police say the activists incited Dalits (formerly untouchables) at a large public rally in Maharashtra last December, leading to violent clashes that left one person dead. "You know Maoist activities…the intellectual push that translates into violence," senior police official Shivaji Bodakhe, told my colleague Vineet Khare.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere has been nationwide outrage against the arrests.

This is absolutely chilling," tweeted historian Ramachandra Guha. "The Supreme Court must intervene to stop this persecution and harassment of independent voices". The arrests were "McCarthyism taken to another level," tweeted Shekhar Gupta, editor of The Print, referring to Senator Joseph McCarthy's reign of terror in the United States in which he exploited the public's fear of Communism . "You can't call people you disagree with terrorists and lock them up."

Others said the crackdown was reminiscent of the Emergency in 1975, when then prime minister Indira Gandhi suspended civil liberties, threw opposition leaders and journalists in prison and gagged the media.

Although many of its ancient texts encourage inquiry, doubt and challenge, India has a chequered history of dissent.

Successive governments have often easily caved in to demands from fringe groups: India was the first to ban Salman Rushdie's 1988 novel, The Satanic Verses, which many Muslims regard as blasphemous. International publishers have been forced to recall and destroy books written by scholars following pressure from little-known right-wing Hindu groups. One of the country's best-known artists, MF Husain, was hounded out of the country after he was accused of obscenity by hard-line Hindu groups.

Antiquated colonial laws remain on the books and continue to undermine free speech. For decades, governments have used a colonial-era sedition law against students, journalists, intellectuals, social activists, and those critical of the government. The Indian state, which often appears to be feeble or unwilling to impose the rule of law, can be selectively harsh on dissenters.

What is different this time, many say, is a concerted campaign by the government to target dissenters.

AFP

AFPMr Modi himself and his party have been accused of using dog-whistle politics - coded, divisive messages - to whip up religious tension and stoke sectarian politics. In a culture of what many believe is a growing politics of hate, "whataboutery" and finger pointing, people critical of Mr Modi's government and party have often been branded as "urban Maoists", or anti-national, much like US President Donald Trump continues to label reporters "enemies of the people".

The upshot is a rising lynch-mob mentality that has begun to pervade many aspects of life.

On bloodthirsty prime time shows on government-friendly news channels, all propriety and decorum is thrown to the winds as selected guests are targeted and shouted down by anchors and guests who support them.

Since Mr Modi stormed to power in 2014, vigilante cow protection groups have lynched more than 20 people, the majority of them Muslims, for transporting beef. In homes and streets, people speak of what many say is an imagined threat to the future of Hinduism - it's a strangely majoritarian nationalism based on past glory and present victimhood. Large parts of the mainstream media, heavily dependant on government advertising in a sluggish economy, prefer to remain silent.

All this has corroded Indian democracy. Many believe the quiescence of the middle class, the silence of the media, the failure of the political parties to support dissent and now a growing muscular nationalism is to to blame for the state of affairs.

"The silencing of dissent, and the generating of fear in the minds of people violate the demands of personal liberty, but it also make it very much harder to have a dialogue-based society," Amartya Sen, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, remarked at a lecture last year.

Indians have not turned intolerant, he said. In fact, "we have been too tolerant even of intolerance". India, clearly, needs more dissent, not less.