The Indian coin that set off millions of messages

BBC

BBCIndia's central bank is reckoned to have sent out hundreds of millions of text messages in the last couple of days - all part of a rearguard effort to protect the value of the Indian currency.

Don't be too alarmed, the Indian economy isn't about to tank - not quite yet, anyway. The bank's herculean campaign is only designed to ensure the integrity of the country's humble 10 rupee coin - worth just 10 US cents or 10 UK pence.

It's powerful evidence of just how seriously governments take their task of ensuring the illusion that the cash in our pockets actually has value. As I'll explain, the truth is that money is the greatest confidence trick in the history of humanity.

The issue in India is simple: many people don't seem to believe that the 10 rupee coins are real and, as a result, they are unwilling to accept them.

Rumours that the coins are fake - allegedly started in the western state of Gujarat - have now spread across the country. Fourteen different kinds of 10 rupee coins have been issued by the bank between 2009 and 2017, adding to the confusion.

"Nobody accepts the coins - grocery shops, tea stalls, nobody accepts it", an auto rickshaw driver in the southern state of Tamil Nadu told BBC Tamil.

In the southern city of Hyderabad, a young girl told BBC Telugu she had been saving up to buy her brother a gift but several shop owners wouldn't take her 10 rupee coins.

A man on his way to a job interview was forced to get off the bus because the conductor wouldn't accept 10 rupee coins, the only currency he had.

"They say it's because the other passengers don't accept the coins in return", explains a shop owner who also said bus conductors wouldn't take the coins.

It sounds trivial - why worry if people shun one small denomination coin? Yet, it is anything but trivial as the response of Indian authorities shows.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLike tens of millions of other people in India I received a text message this morning from the central bank urging me to accept the 10 rupee coins "without fear".

And, just in case this hadn't assuaged my anxiety, there was a number I could call - 14440.

I dialled it. A second or two later, the bank called back - not in person, sadly, but as a recorded message, explaining that the Indian government has minted a number of different 10 rupee coins over the years, each with a different pattern, and that all are valid.

Members of the public should, it exhorted, "continue to accept coins of the 10 rupee denomination as legal tender in all their transactions without any hesitation".

The reason India is going to all this effort is because it knows, like every other government, that all money is worthless.

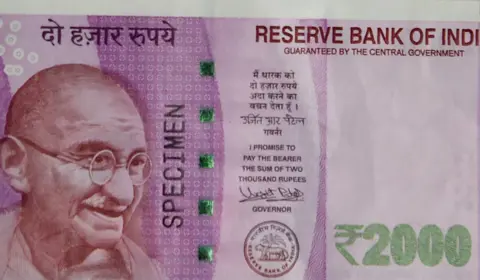

Pull a note out of your wallet and take a close look at it. Virtually all paper money is inscribed with the same promise: "to pay the bearer" whatever the value of the note is.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIf you've ever wondered what this means you need wait no longer. Ask your government to honour that promise and you'll simply get another note of the same value in return. Your colourful piece of paper will be replaced with another colourful piece of paper.

So what does this tell us about the real value of money? What it says is that money is nothing more than a figment of our collective imagination.

The worth of money isn't based on the inherent value of the paper or metal - it's forged from a collective act of trust.

The "chai wallah" who sells me my spicy morning tea accepts my money because he trusts that the neighbouring shop will accept it in return for a bag of rice.

That shopkeeper, in turn, takes it on trust that the same money can be exchanged for a cable TV subscription, a gold bangle for his daughter's wedding or whatever else he wants.

The real value of money is this system of trust.

AFP

AFPIt is an extraordinarily powerful construct - but potentially fragile.

In his book "Sapiens", Yuval Noah Harari argues that the system of trust money embodies is the most potent unifying force human beings have ever created because it bridges language, culture, laws, religion - everything.

"Even people who don't believe in the same god or obey the same king are more than willing to use the same money", writes Mr Harari.

"Osama bin-Laden, for all his hatred of American culture, American religion, and American politics, was very fond of American dollars."

But the system is fragile because trust is ephemeral; it can be lost. And that's why the Indian authorities are so worried.

The Indian central bank's PR offensive in defence of the 10 rupee coin is an attempt to ensure that the peoples' faith in the rest of the country's cash isn't undermined.

If that happened, the entire economy really would collapse.