Was Delhi gang rape India's #Metoo moment?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFive years after the notorious gang rape and murder of a 23-year old physiotherapy student on a bus in Delhi, the BBC's Geeta Pandey asks if India is a better place for women today.

First, a recap of the horrific crime - the young woman and her male friend had boarded the bus just after 9pm on 16 December 2012.

She was then gang-raped by the driver and five other men on the bus while her friend was badly beaten up. Naked and bloodied, the couple were thrown by the roadside to die.

They were taken to hospital after some passers-by found them and called the police. She clung to life for a fortnight before succumbing to her injuries. Her friend lives, scarred for life.

The brutality of the assault stunned India and the press dubbed her Nirbhaya - the fearless one.

But I had met my own Nirbhaya a decade before that, while I was producing a BBC radio feature on rape in India.

I met her at a shelter for women run by an NGO in central Delhi. She was from a poor family in Gujarat, a member of a travelling tribe that has no fixed address.

The woman had come to the capital along with her husband and young child.

For a few months the couple had worked as day wage labourers and were returning to Gujarat for a visit.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAt the railway station, in the melee, she was separated from her family. They boarded the train as it moved and she got left behind.

As she sat on the platform weeping, a kindly looking Sikh man offered help. He told her he was a truck driver and would take her home.

She took him up on his offer since she had no money.

For the next four days, she was driven around on the truck, brutally gang-raped by the driver and three other men.

Believing that she was about to die, they threw her by the roadside which is where she was found and taken to hospital.

When I went to meet her, she had just been brought in from the hospital after months of treatment.

Her body resembled a war zone. Her insides were so badly damaged that she had to walk around with a pipe that came out of her abdomen and was attached to a bag. She showed me burn marks on her breasts where her rapists had branded her with cigarettes.

She had no idea where her family was. The NGO said their attempts to track them down had failed.

I spent more than an hour talking to her.

It made me sick just to hear what she had been through, about the brutality human beings can be capable of.

I was traumatised and, for the first time in my life, I felt fear. And I projected my fears onto two women closest to me - my sister and my best friend, who was also a BBC colleague, two very independent and feisty women.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEvery time they would visit me, I would insist as they left that they messaged me once they reached home.

They humoured me initially, sometimes they would get irritated because if they forgot, I'd call them in the morning and harangue them. Sometimes they made fun of me.

And then 16 December 2012 happened.

As the Indian press gave out gory details of the brutal assault, the trauma was brought alive for a horrified nation.

For a fortnight, as Nirbhaya lay in her hospital bed fighting for life, television channels and newspapers reported every little detail of what had been done to her.

My sister and my friend no longer made fun of me.

But that was not the only change. Giving in to the demands of protesters who took to the streets across India, the government brought in a tougher new law to deal with crimes against women.

But the biggest change has been the one in attitudes - sexual attacks and rapes have become topics of living room conversations and that is a huge deal in a country where sex and sex crimes are a taboo, something to be brushed under the carpet, not discussed at length.

Getty Images

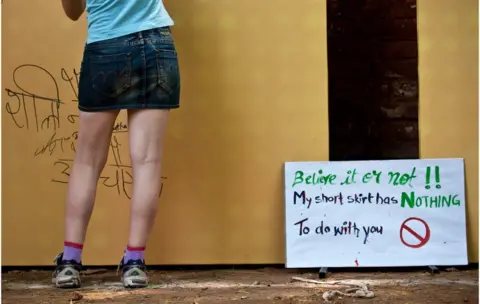

Getty ImagesTaking control of the conversation is the first step to India becoming a better place for women. And this conversation has spilt on to social media and India is in the grip of, to borrow a phrase from Nobel laureate VS Naipaul, a "million mutinies now".

Every incident, big or small, is being discussed and written about, and women's rights to safe living and equality have been under much greater scrutiny. In recent years, we've written about many of these campaigns:

- Women fighting to enter Hindu temples

- Muslim shrines are no longer out of bounds for women

- Women who are challenging traditional beliefs about menstruation

- How Muslim women fought, and won, the battle against instant divorce

- College students who are campaigning to break the oppressive cage of patriarchal restrictions.

It's not that women were not speaking out earlier - we've had warriors who've been fighting for decades, challenging every thought and idea rooted in patriarchy.

Over the next few days, we'll be bringing you stories of some of these women who have relentlessly campaigned for a better, safer and more inclusive world for themselves and others.

The question is: have they been successful?

Recently released National Crime Records Bureau statistics for the year 2016 paint a dismal picture - crimes against women continue to rise.

We still have thousands of brides murdered for dowry, tens of thousands of women and girls raped, hundreds of thousands of incidents of domestic violence and female foetuses being aborted.

In the past week alone, we have reported on the brutal rape, torture and murder of a six-year-old, the gang rape of a 16-year-old cancer survivor and a Bollywood actress who was sexually harassed by a fellow passenger on a flight.

But what is heartening is the refusal of women to give up their fight. And that's where our hopes lie for a better future for women in India.