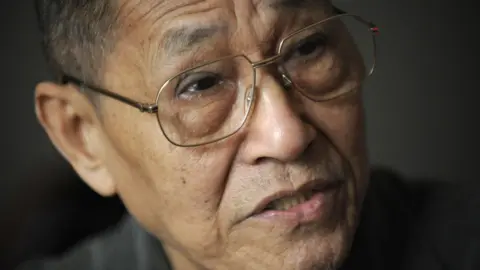

Bao Tong: Champion of Chinese political reform dies at 90

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBao Tong, the most senior Communist Party official imprisoned over the Tiananmen protests that shook Beijing in 1989, has died at 90.

He championed political reform in the 1980s during pro-democracy protests.

But after crushing the movement, the Communist Party expelled Bao and jailed him for seven years.

Even as Chinese activists around the world mourn his passing, the news has drawn no reaction in his own country, where the internet is heavily censored.

In the years that followed, the historic protests at Tiananmen effectively disappeared from public record - and so did all mention of the massacre, whose exact toll still remains unknown.

Even today, a search for Bao's name on Weibo, China's heavily censored version of Twitter, yields no results. The screen says they cannot be displayed because of "relevant law and regulations".

As a result of the Communist Party's harsh crackdown on any topic related to the 1980s protests, or any other form of dissent, few young Chinese know Bao's name.

But condolences poured in from everywhere else after his son Bao Pu confirmed his death on Wednesday, saying his father had died peacefully that morning in Beijing, the city he had called home for decades.

Wang Dan, a student leader from the Tiananmen protests, hailed him on Twitter as a reformer and rebel who was crucial to China opening up. Although he is "against" the Chinese Communist Party, he wrote that he would still like to "express utmost respect" for former party officials like Bao who fought for change before eventually leaving.

In the 1980s, Bao was a top aide to Zhao Ziyang, then general secretary of the Communist Party - the same post now held by Xi Jinping. Zhao had been in favour of reform and a leading figure of that faction within the party.

Born in 1932 in China's eastern Zhejiang Province, Bao joined the Communist Party in 1949, the same year it took control of mainland China.

In the 1980s, he rose to become political secretary to Zhao when he was the premier and subsequently general secretary. He served as a member of the party's central committee and director of its political reform office.

Bao helped draft political and economic reforms to overhaul the structures of power that had been largely left unchanged since Mao Zedong's death in 1976.

He was one of the architects of the model of collective leadership that the party later ushered in to prevent power from being centralised in the hands of a single leader.

But in 1989 as the pro-democracy protests grew and engulfed more of China, the hardliners in the party became more anxious about their future. Eventually the reformists lost and the protests were brought to a brutal end.

The careers of both Zhao and Bao, who had openly sympathised with the protesters, ended abruptly days before the massacre on 4 June.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy then Zhao had been dismissed from his post and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. He died in 2005.

Bao was arrested in May 1989 and tried in 1992. He was found guilty of "revealing state secrets and counter-revolutionary propagandising" - a charge he denied. He was expelled from the party and sentenced to seven years in prison.

Even after he was released, he remained under strict state surveillance. And yet in that time he became one of China's most outspoken dissidents and critics of the party. He demanded that Chinese leaders rehabilitate "June 4", the day of the massacre at Tiananmen Square - he wanted them to acknowledge the protests and what happened that day.

Sine 2012 he had been active on Twitter, where he regularly commented on China's politics.

In an interview with BBC Chinese in 2019 - on the 30th anniversary of the Tiananmen protests - Bao said he felt like he achieved "nothing" in his life. He said the political reform he had pushed for and the future he had hoped China would have had never materialised.

Bao's wife, Jiang Zongcao, died in August this year. She was also 90. The couple have two children - Bao Pu and Bao Jian.

Days before he died, Bao celebrated his 90th birthday. His son shared what he believed were his father's last words to the world: "It doesn't matter whether I reach 90, what's important is the future we all should fight for... we should do what we are supposed to do, then we'll realise our value, the value of our life."