How long will Shanghai's lockdown last?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Chinese city of Shanghai has been under Covid lockdown for over a month, affecting the lives of more than 25 million people.

Local authorities have now said they will relax rules soon, but many people remain confined to their accommodation.

What's the current situation in Shanghai?

Shanghai local council announced on Monday that the city will "resume normalcy in June" - and that 15 out of 16 districts had achieved a "zero-Covid goal".

However, on the same day, Shanghai's health authority recorded more than 800 new cases.

On the ground, many people complain that restrictions are as tight as ever, and that they are still unable to leave home, even if the risk status of their area has changed.

On Chinese social media, posts complaining about conditions - such as local merchants telling people not to make reservations because they are unable to work - have been censored.

Many people worry that the de facto lockdown will last longer.

Why has the lockdown lasted this long?

Shanghai has been under lockdown for seven weeks - a lot longer than the city's initial plan of a week-long lockdown staggered over different parts of the city.

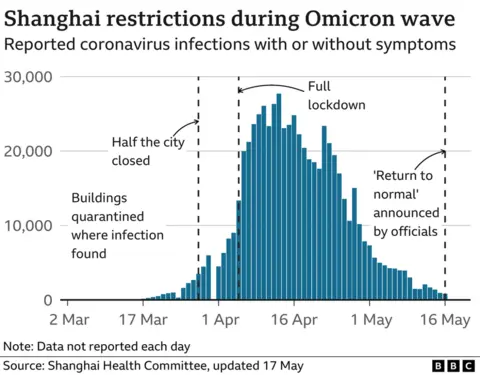

It was decided to extend a city-wide full lockdown indefinitely when cases surged to more than 13,000 a day at the beginning of April.

Workplaces, schools and a number of factories have now been closed for weeks. Fences have been installed on roads and at the gate of community compounds to restrict population movement.

Millions of people staying at home have been relying on food deliveries from the government, after commercial food deliveries were forbidden.

Even emergency access to hospitals has been restricted.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhy is Shanghai's lockdown a big deal for China?

Before this year, Shanghai had escaped the worst of China's Covid lockdowns - even when cases roses to nearly 1,800 in March 2021.

By comparison, Xi'an (population nearly 13 million) closed down because of 100 cases and Yuzhou (more than 1.1 million people) closed down after just three cases.

The main reason is Shanghai's importance for the Chinese economy.

Shanghai is responsible for more than 3% of China's GDP, and more than 10% of China's total trade since 2018.

Airports in Shanghai have also been responsible for bringing in nearly half of the protective equipment and medicine that China needed in the early days of the pandemic, according to local news outlet Caixin.

In 2020, cargo flights into Shanghai Pudong International Airport accounted for 3.4 million tonnes of goods - a million more than the airports in the cities of Beijing, Guangzhou and Shenzhen combined.

Studies from the Chinese University of Hong Kong show a two-week lockdown in megacities like Beijing or Shanghai could cost China 2% of its monthly GDP.

China's monthly GDP in 2021 was 9.5tn yuan ($1.4tn) on average, so the country would stand to lose about 190bn yuan ($29.8bn) for each week the lockdown continues.

Is this lockdown working?

The World Health Organization (WHO) has expressed doubts over whether Shanghai's lockdown strategy is effective.

While many countries are now relying on vaccination and improved treatments, China has stuck to a policy of lockdowns and other restrictions.

The WHO says that with more transmissible Omicron variants spreading, this approach is not "sustainable."

"The virus is evolving, changing its behaviour. With that... changing your measures will be very important," said Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesu.

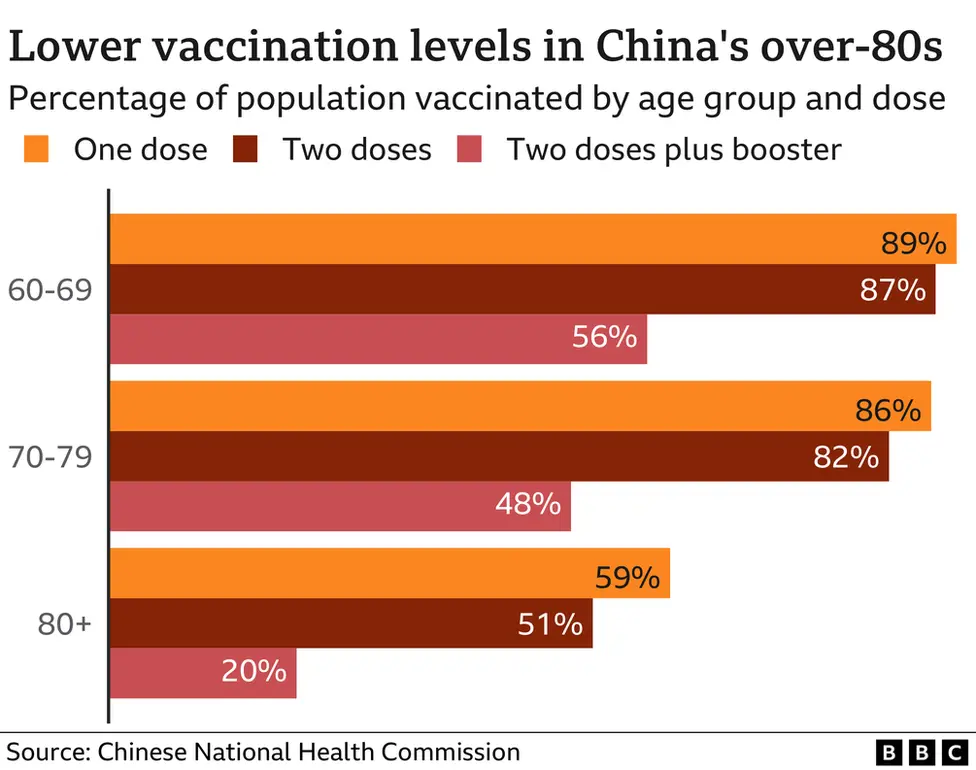

China has administered more than 3.3 billion doses of Covid vaccine and the number is still increasing.

But vaccine rates among people over the age of 80 - who are among the most vulnerable - remain a lot lower than other age groups.

Another problem is that China has heavily relied on domestically-produced vaccines which have struggled against the latest variant.

However, the Chinese government has said that if prevention and control measures are relaxed, it will "inevitably lead to the death of a large number of elderly people".

It insisted that the current policy is "bringing Covid-19 under control at the minimum social cost in the shortest time possible."

Additional reporting by Tim Bowler; Graphics by Rob England and Jana Tauschinski