China: Peeking into the private lives of livestreamers

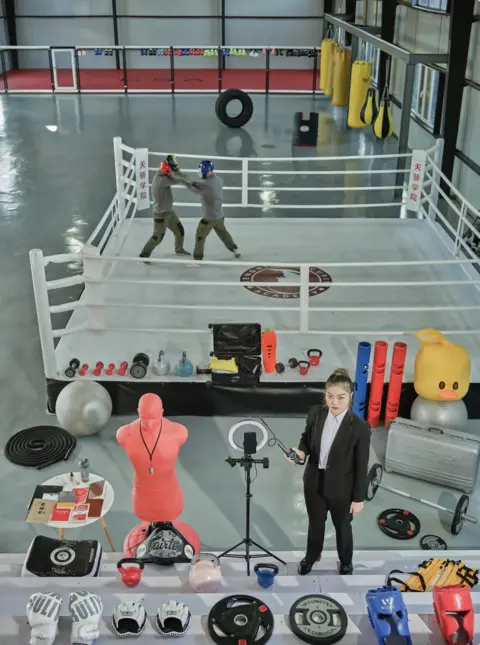

From a pigeon expert to a professor, a new photo series seeks to shed light on one of China's fastest growing communities - livestreamers.

Chinese photographer Huang Qingjun is no stranger to capturing the intimate personal lives of ordinary Chinese. In 2003, he embarked on a unique project - documenting the possessions that people across China own.

The project series - called Jia Dang, or Family Stuff - has taken him across a multitude of provinces for nearly two decades, snapping families as they lay out all their worldly possessions.

In the latest instalment of his project, Mr Huang has turned his lens on people who make their living from livestreaming.

Huang Qingjun

Huang QingjunLivestreaming exploded in popularity during the pandemic, providing hours of entertainment as millions were confined to their homes for weeks on end.

It was not just viewers who were hooked. More digitally-savvy entrepreneurs also went online to peddle goods. In February 2020 at the height of China's Covid-19 epidemic, Taobao, the Chinese platform which sees the largest number of livestreaming sales, saw an increase of 719% in new sellers across the country.

And as lockdowns continue to be imposed across provinces and cities, the appetite for livestreaming content has remained strong.

"In the past two years, people's daily life and consumption habits have changed a lot," Mr Huang tells the BBC.

"Now people in the post-pandemic era perceive society through smartphones, and short broadcasts and livestreaming have become a window for individuals to showcase their talents."

Huang Qingjun

Huang QingjunPerhaps more importantly, livestreamers have presented some respite from loneliness, especially at a time when restrictions and quarantine have left many starved of human connection and company.

"The 'iron friendships' between the audience and the livestreamer, forged in the livestream broadcast room, is also part of what sustains the spirit of people,'" says Mr Huang.

Huang Qingjun

Huang Qingjun Huang Qingjun

Huang QingjunIn his earlier photo series, Mr Huang had to travel to some of the remotest parts of China to persuade people to pose for him. Some of them had never even been photographed in their lives, much less owned a camera.

They often displayed their meagre yet prized possessions: a television, a few pots and pans, and several pairs of worn shoes.

But he has now focused on a group of technology-savvy people from diverse backgrounds, ranging from a chemistry professor and a food deliveryman to a pigeon aficionado and a noodle seller.

Many of his subjects this time are pictured turning their own lenses on themselves, surrounded by professional filming equipment, electronic appliances and sporting goods.

Huang Qingjun

Huang Qingjun Huang Qingjun

Huang Qingjun"By focusing on [the livestreamers'] belongings … and the tools they rely on for their livelihood, we can see the changes of an era," says Mr Huang.

"With the rapid development of Chinese society, the living standards of Chinese people have also undergone great changes, and more families enjoy the dividends brought by this development."

The World Bank estimates China's gross national income per capita has grown more than tenfold in two decades, from $940 (£714) in 2000 to $10,550 in 2020, creating a swelling middle class with disposable income.

Huang Qingjun

Huang QingjunBut the photographer adds that living through a pandemic has forced many to re-think their patterns of consumption.

"Now people have recognised the importance of the environment, and every household has begun to sort their rubbish [for recycling]," he says. "Because the pandemic has too many uncertainties, it also has had a great impact on people's incomes and household consumption patterns."

Mr Huang hopes this gradual orientation away from excessive consumerism will serve as inspiration for his next instalment of the series.

"I hope that I can do a minimalist lifestyle in the future," he says. "And the last work of my Family Stuff series will be of my own belongings."

Huang Qingjun

Huang Qingjun Huang Qingjun

Huang Qingjun