Crazy love: Behind China's crackdown on K-pop and other fan clubs

Getty Images

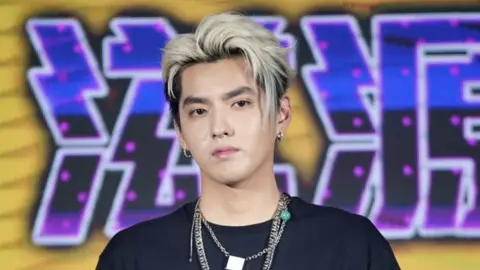

Getty ImagesWhen Chinese-Canadian pop star Kris Wu was arrested on suspicion of rape last month, some of his fans immediately banded together online - with plans to break him out of prison.

"Girls, there's strength in numbers, let's fly to Beijing and rescue him," one of them posted on microblogging platform Weibo.

Others said they were prepared with shovels to dig tunnels and pliers to cut wired fences.

But it was not long before such discussions - as well as the accounts that shared them - were deleted.

As China's increasingly obsessive celebrity fans continue to make headlines for all the wrong reasons, authorities have made it clear that such behaviour would not be tolerated.

"The chaos in celebrity fan clubs, exposed by the 'Kris Wu incident', shows that bad fan culture has reached a critical moment that must be corrected," the country's top disciplinary body said in a post, adding that thousands of "toxic" fan comments and groups have since been deleted.

Two weeks ago, China's internet watchdog said in a 10-point plan that it would stop the dissemination of "harmful" information in celebrity fan groups, including gossip and verbal abuse.

Any platforms that do not work to quickly remove such content would also be penalised.

"There needs to be a limitation of irrational star-chasing," it said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor months, Beijing has ramped up efforts to rein in what it calls "chaotic" fan culture - a move welcomed even among some celebrity fans.

A Weibo user who regularly posts updates about entertainment news, said: "Crazy fans have really given us all a bad name. Even I get annoyed when I see those large groups of fans crowding the airport to see their idols."

Many members of these groups are not just people harmlessly cheering on their favourite stars.

In many instances, their behaviour has turned toxic.

From stalking to cyberbullying and spreading rumours, organised fan groups have increasingly taken their "love" to crazy extremes.

Last year, a fan group for popular actor Xiao Zhan shut down an entire fan fiction website over a piece which had depicted him as a crossdressing teen in love with another male idol.

Fearing that the story would "tarnish" their idol's image, they reported it to the authorities as "underage pornography" - which quickly led to the site being taken down.

This, in turn, infuriated loyal readers of the site, and an army of "anti-fans" were born, as they began campaigning for people to boycott the many brands Xiao was ambassador for.

Both sides then got embroiled in an ugly cyberwar - with images and even addresses of people being posted online for abuse.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd it's not just that.

Fans have also regularly made the news for spending extravagant amounts of money on their idols - with some students reportedly going into debt.

Just last Sunday, Weibo suspended a fan club of singer Jimin - a member of K-pop boy band BTS - over claims that it had raised funds illegally.

The account, which had more than 1.1m followers, crowdfunded a record-breaking 1m yuan ($154,770; £112,460) in three minutes - money that went to customising the exterior of an airplane in honour of his 26th birthday.

Allow Twitter content?

Everything from the plane tickets to the cups used onboard were also customised to say "Happy Jimin Day", according to reports.

That was on top of plans to take out full-page ads in the New York Times and The Times in the UK to mark his birthday.

In May, eager fans of reality TV show Youth With You enraged the public over a controversy involving food waste.

As part of the show's marketing strategy - which pitted trainee singers against one another - fans could cast more votes for their favourite male idols by scanning QR codes inside milk bottle caps.

It led to people buying milk in bulk with no intention of drinking it, and footage soon emerged of fans pouring large amounts of milk down the drain after voting.

Chinese fans = data labourers

Even though obsessive fan culture is hardly unique to China, experts say that the scale is greater there thanks to a massive internet population that is also highly-engaged.

"Participating in Chinese fandom culture is no longer simply a hobby, but a form of data labour," said Liaoning University's Dr Bai Meijiadai.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFrom celebrity ranking lists based on followers and engagement, to singing TV contests allowing the public to cast votes, fans have become active participants in feeding the idol worship machine like never before.

In 2018, Kris Wu made headlines in the US when he swept the iTunes music chart - taking not just the No. 1 spot, but also seven of the top 10 songs. For a singer who was practically unknown in North America, it was quite the achievement.

While critics immediately thought that it was the work of bots, investigations found that it was in fact driven by his legion of fans, who had worked together to buy his albums to push up sales.

But it is also precisely this kind of organised campaigning that worries the Chinese authorities, experts say.

"There has been growing concern that fan clubs can mobilise, either in person or online, to stage protests for their favourite stars," said the BBC's China media analyst Kerry Allen.

But there also appears to be a moral aspect to this crackdown.

Actress Zheng Shuang, for example, sparked outrage after it was alleged that she had abandoned two children born to surrogates abroad, before news broke that she had been evading tax.

She has since been scrubbed from the Internet.

"If celebrities are expected to be role models, then it is natural that online fan groups need to be regulated too to promote a healthy internet culture overall," Deakin University's Dr Jian Xu, who researches Chinese media culture said. "It is an attempt to protect young people from being negatively impacted."

End of the road?

As Beijing bears down on fan culture, some online groups may be feeling lost - their worlds have changed seemingly overnight.

Already, all the major social media platforms have responded to the government's call, removing celebrity ranking lists and shutting select fan accounts. Competitive idol reality TV shows, many which rely on fan participation, were also banned this week.

"The crackdown may make fandoms 'boring' for some individuals who were all about the excitement of getting their idol to the top of the lists," said Allison Malmsten, a China market analyst from Daxue Consulting.

But she noted that this hardly signals the end of the road for them - they will just be less visible online.

"The crackdown is not the end of celebrity worship, rather it's a way to reduce uncivilised behaviour that results from celebrity worship."