'The grim reality of reporting in China that pushed me out’

It was a reminder of the grim reality of reporting in China to the very end.

As my family scrambled to the airport - late and unprepared from the last-minute packing - we were watched outside our home by plainclothes police, who then followed us to the airport and tailed us through check-in.

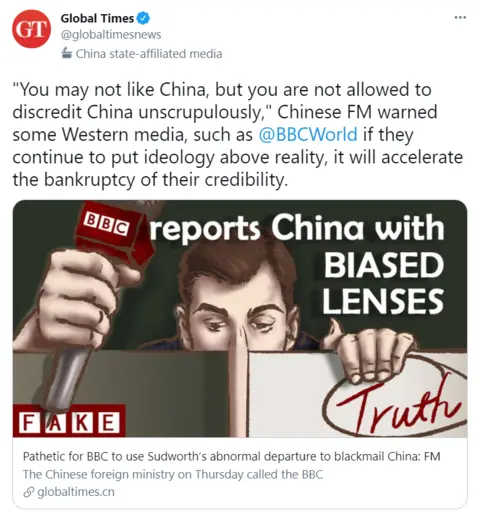

True to form to the very end, China's propaganda machine has been at full throttle, denying I faced any risks in China, while simultaneously making those risks abundantly clear.

"The Foreign Ministry said they are not aware that Sudworth was under any threat," the Communist Party controlled Global Times said, "except that he may be sued by individuals in Xinjiang over his slanderous reports."

The chilling effect of such statements lies in the reality of a court system run - like the media - as an extension of the Communist Party, with the idea of an independent judiciary dismissed as "an erroneous Western notion".

China's ministry of foreign affairs has continued the attacks, using the podium at its daily press briefing on Thursday to criticise what it called the BBC's "fake news".

It played a video clip from our recent interview with Volkswagen in China over its decision to operate a car plant in Xinjiang, suggesting that this "is the kind of report that triggers the anger of the Chinese people".

It's an unlikely claim, of course, given that the vast majority of the Chinese people cannot see any of our reporting, which has long been blocked.

But while all of this has brought my posting to a fraught and fretful end, it is worth remembering that mine is just the latest in a long line of foreign media departures in recent years.

And it is part of a far bigger battle that China is waging over the global space for ideas and information.

Media becomes battleground

"Economic freedom creates habits of liberty," former US President George W Bush once said in a speech urging China's acceptance into the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

"And habits of liberty create expectations of democracy," he continued.

That starry-eyed assumption - that as China grew richer it would grow freer - could still frequently be heard in news analysis and academic discussion of China when I first began working here in 2012.

But my arrival that year coincided with a development that has come to make that prediction seem utterly naïve - the appointment of Xi Jinping to the most powerful job in the country, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party.

EPA

EPAWhile the huge shift in global trading patterns over the years has undoubtedly changed China - unleashing a whirlwind of economic and social change - those expectations of democracy appear further away than ever.

President Xi has used China's already rigid political system to tighten control over almost every aspect of society, and 10 years into his now open-ended tenure, it is the media landscape that has emerged as the defining battleground.

"Document Number 9" - reportedly a high-level leak - identified early on the main targets in that fight: "Western values", including freedom of the press.

And, as the BBC's experience shows, any foreign journalism that exposes truths about the situation in Xinjiang, questions China's handling of the coronavirus and its origins, or gives voice to opponents of its authoritarian plans for Hong Kong, is now firmly in the firing line.

Undermining democratic debate

But as China's propaganda attacks continue in the wake of my departure, it is also notable that foreign social media networks are being used extensively to amplify the message.

Twitter

TwitterThe irony is, of course, that at the same time that the space for foreign journalism is shrinking in China, the Communist Party has been investing heavily in its media strategy overseas, taking full advantage of the easy access to a free and open media.

Its "wolf-warrior" diplomats unleash furious tweet-storms, lambasting foreign reporting - while denying their own citizens access to those very same foreign platforms - in an intensive, co-ordinated strategy across multiple platforms, as documented by this report by researchers from the International Cyber Policy Centre at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

State-media propagandists publish and post their content overseas without restriction, while at home, China ruthlessly shuts down independent reporting, censors foreign broadcasts and websites, and blocks foreign journalists from its own social media networks.

Twitter

TwitterIn this context, my departure can be seen as one small part of an emerging and highly asymmetric battle for the control of ideas.

It is not a happy prospect for the free flow of good, accurate information.

Decreasing access will undermine our ability to understand what is really happening in China, while at the same time, it is is harnessing the power of the institutions of a free press to undermine democratic debate everywhere.

Footprints that lead to the truth

While there are no easy answers, and the idealism of President Bush's prediction has long since evaporated, there is some room for hope.

Much of the information that has been revealed in recent years about the truth of what is happening in Xinjiang has - despite China's dismissal of it as "fake" - been based on its own internal documents and propaganda reports.

In the running of a system of mass incarceration, a modern, digital superpower cannot help but leave footprints online, and the important journalistic effort to uncover them will continue from afar.

I join a growing number of foreign correspondents now forced to cover the China story from Taipei, or other cities in Asia and beyond.

And of course, while depleted in number, there are brave, determined members of the foreign press corps in China who remain committed to telling the story.

Most remarkably, within the tightening confines of the political controls, there are also the few extraordinary Chinese citizens who, at enormous personal danger, find ways round the censorship to do the most important job in journalism anywhere - telling the story of their country in their own words.

Much of what we know about the early days of the Wuhan lockdown came from these citizen journalists, who are today paying the price for that bravery.

I am able to leave the plain-clothes police, for the final time I hope, in the departure hall of a Beijing airport.

In the new global battle for ideas, we should never forget that it is China's citizens who continue to face the greatest risks for telling the truth.