Wuhan marks its anniversary with triumph and denial

Reuters

ReutersWuhan has long since recovered from the world's first outbreak of Covid-19. It is now being remembered not as a disaster but as a victory, and with an insistence that the virus came from somewhere - anywhere - but here.

From the moment a new, pandemic coronavirus emerged in the same city as a laboratory dedicated to the study of new coronaviruses with pandemic potential, Prof Shi Zhengli has found herself the focus of one of the biggest scientific controversies of our time.

For much of the past year she has met the suggestion that Sars-Cov-2 might have escaped from the Wuhan Institute of Virology with angry denial.

Now though, she has offered her own thoughts on how the initial outbreak may have begun in the city.

In an article in this month's edition of Science Magazine she referred to a number of studies that, she said, suggest the virus existed outside of China before Wuhan's first known case in December 2019.

"Given the finding of Sars-Cov-2 on the surface of imported food packages, contact with contaminated uncooked food could be an important source of Sars-Cov-2 transmission," she wrote.

From one of the world's leading experts on coronaviruses, even the discussion of such a possibility seems unusual.

Could a spiralling outbreak of infection that almost destroyed Wuhan's health system, sparked the world's first Covid lockdown and spawned a global catastrophe really have arrived on imported food without any signs of similarly devastating outbreaks elsewhere?

But with the virus vanquished, the idea that it is a foreign import is repeated with almost unanimity across this city of 11 million people.

"It came here from other countries," one woman running a hotpot stall in a busy street tells me. "China is a victim."

"Where did it come from?" the next-door fishmonger repeats my question aloud, and then answers: "It came from America."

On 23 January last year, the Chinese authorities severed transport links out of Wuhan and confined the city's population to their homes.

The tough lockdown coincided with the annual spring festival celebrations and came too late to prevent the global spread of the disease - five million people had already left the city ahead of the holiday.

Doctors' warnings had gone unheeded and, in an outpouring of anger on the Chinese internet, the authorities stood accused of covering up the initial outbreak in the interests of political stability.

One year on, there's little sign of that anger in Wuhan today. In fact it's the humdrum normality that is striking - the traffic jams, the bustling markets and busy restaurants.

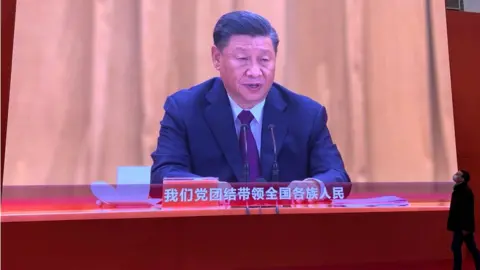

Its success in eventually bringing the virus under control is now being celebrated in a giant exhibition hall, complete with models of medical workers in hazmat suits, installations of hospital beds and - everywhere you look - giant portraits of President Xi Jinping.

The accompanying texts mention his "all-out war" against the pandemic, his "resolute decision making" and how he has been willing to share "China's solutions" with the world.

There can be no doubting the success of China's mass testing programmes, its tracing apps and the widespread mask wearing.

But its strict enforcement of lockdowns, with little hand-wringing over the impact on individual rights, may be far less easy for democratic countries to emulate.

"The strategic success achieved in this battle fully manifested the strong leadership of the Communist Party of China and the significant advantages of the socialist system of our country," the exhibition proclaims.

Despite China's promise of international co-operation, the world is still no closer to an answer to the biggest question of them all - where did the virus come from?

Many prominent scientists believe that - based on past outbreaks - the most likely source of the coronavirus is a natural one, a "zoonotic" leap from bats - known to harbour such viruses - to humans, possibly via an intermediate species.

But China has produced very little evidence to show the work that's been done in its search for the source, in particular the testing of historic human samples stored by hospitals to determine where and when the virus really started spreading.

Those scientists who argue that the possibility of an accident at the Wuhan Institute of Virology should also be included as part of any investigation are curious about this apparent silence.

"I find it very unlikely that such investigations would not have already occurred," Alina Chan, a molecular biologist at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, told me.

"It's a serious risk to resume life as usual without knowing where a dangerous human pathogen came from."

Instead of publishing its own evidence though, China appears to be taking an anywhere-but-Wuhan approach, with state media cheerleading the idea that the virus may have arrived in Wuhan on frozen food imports or talking cryptically of "multiple origins".

At a recent daily press briefing, I asked China's Foreign Ministry spokesperson, Hua Chunying, why such narratives were being promoted in the absence of real scientific evidence.

"Your question reveals your prejudice against China," she replied. "Reports have emerged from Australia, Italy and many other countries that the coronavirus was found in multiple places in the autumn of 2019."

"Aren't these all facts?" she asked.

Not according to Alina Chan, who told me that such studies "lack validation" and some have been conducted without "the most basic controls".

"They do not present persuasive scientific evidence that the virus was circulating outside of China before the late 2019 outbreak in Wuhan," she said.

"The earliest detected cases and outbreak were in Wuhan. Early cases outside of China were found to have travelled from Wuhan. The most similar viruses have been found inside China."

Interestingly, scientists who have found themselves disagreeing strongly about the likelihood of the lab-leak theory, suddenly find themselves very much aligned on whether the virus came from abroad.

"I do not find the data linking Sars-Cov-2 to frozen foods to be credible," Kristian Andersen, a professor of immunology and microbiology at the Scripps Research Institute in the US, told me.

As someone who is a firm supporter of China's insistence that the virus could not have escaped from a lab, he gives its latest position much shorter shrift.

"All the available evidence points to an emergence of the virus somewhere in China in late 2019," he said.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesProf Shi Zhengli recently told the BBC in an exchange of emails that she'd welcome "any form of visit" by an inquiry team to the Wuhan Institute of Virology to rule out the possibility of a lab leak.

But to a follow-up email asking about the alignment of her discussion of possible foreign origins with the Chinese government's own narrative, she sent another reply.

"Your question is not friendly," she wrote.

After months of delay and wrangling with China about access, a World Health Organization team has arrived in Wuhan to begin its inquiry into the origins of the virus.

Their terms of reference hint at the politics behind the scenes, with the document mentioning many of China's talking points, including foreign origins and food-chain transmission.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDr Daniel Lucey, a physician and infectious disease professor at the Georgetown Medical Centre in Washington, suggests the stage is being set for a foregone conclusion.

"In my view, if you line up side-by-side the WHO's terms of reference with the Shi Zhengli Science article," he told me, "then it is clear that the overarching strategic narrative is that the origin of the virus is outside of China."

The crisis that began in Wuhan is now the world's crisis and, with so many lives and livelihoods lost, answers are desperately needed.

If the virus came naturally from bats, an understanding of that pathway is important to protect humanity from the risk of repeated "spillover" events from the same source.

If it leaked from a lab, an urgent review of safety protocols is needed - not just in China but globally.

Scientists are beginning to wonder if those answers will ever be forthcoming.

"It's undeniable now that politics have gotten in the way of science," Alina Chan said.

"I just hope that the WHO team will relay the details of their experience so that the public can understand what the limitations of their investigation are."

In Wuhan's giant exhibition hall, the city's place in history is again called into question by one of the concluding sign boards which says Covid-19 broke out "in multiple places around the world".

For China, this city's past is now propaganda and the truth, like the virus, is being brought under tight control.