Coronavirus: How do you quarantine a city - and does it work?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith two days until the Chinese New Year, the railway station in Wuhan should be buzzing.

Across the country, millions of people are heading home to see loved ones. But in China's seventh biggest city - home of the coronavirus - most platforms are deserted.

As of 10:00 on Thursday (02:00 GMT), buses, trains, subways and ferries were stopped from leaving the city.

Flights were also suspended. Roads are not officially closed, but roadblocks have been reported, and residents have been told not to leave.

So the question is - can you quarantine an entire city? And if you can - does it work?

Reuters

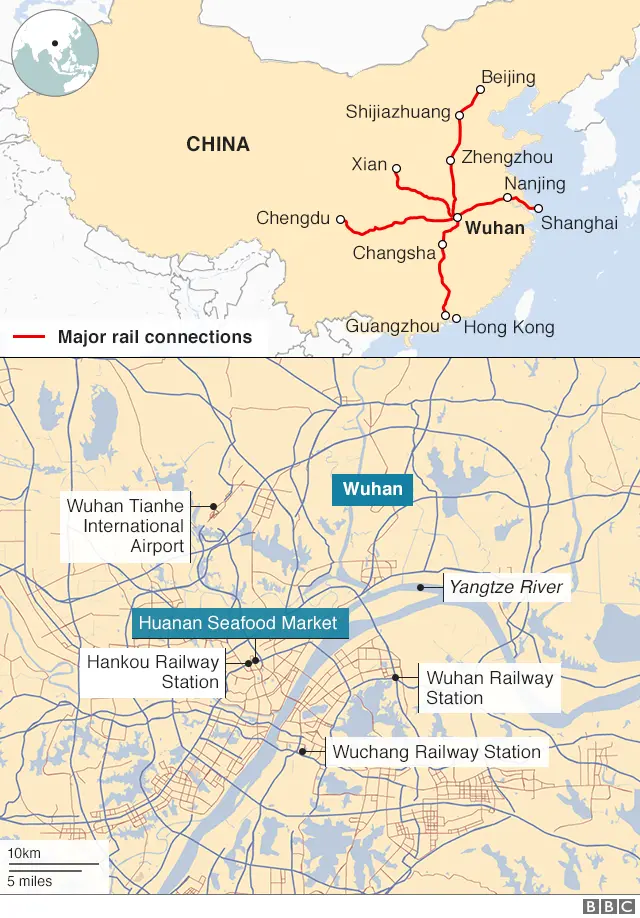

ReutersWuhan is a huge place - the 42nd biggest city in the world, according to UN data - and cannot easily be turned into an isolation ward.

More than 20 major roads come into Wuhan, plus dozens of smaller ones. Even with public transport closed, sealing the city would require a massive military effort.

"The only way you could do it, realistically, would be to ring-fence the city with the PLA [Chinese military]," says Professor Adam Kamradt-Scott, a health security expert from the University of Sydney.

But even if they do it, where - literally - would they draw the line? Like most modern cities, Wuhan sprawls into smaller towns and villages.

"Cities are shaped in unorthodox ways," says Professor Mikhail Prokopenko, a pandemics expert also from the University of Sydney,

"You can't really block every road and every connection. It may be possible to an extent... but it's not a foolproof measure."

Gauden Galea, the World Health Organization's representative in China, puts it more bluntly.

"To my knowledge, trying to contain a city of 11 million people is new to science," he told the Associated Press. "We cannot at this stage say it will or it will not work."

And - even if it proves possible to shut the stable door on Wuhan - the horse may already have bolted.

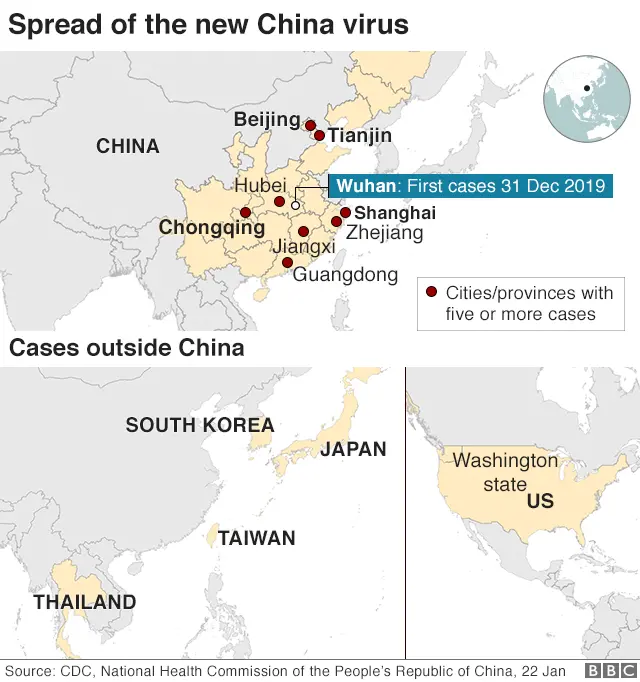

The Wuhan virus was reported to the WHO on 31 December. It wasn't until 20 January that officials in China confirmed it could be passed human-to-human.

By that time, tens of thousands of people had been and gone from the city. The virus has since been reported across China and Asia, and even in the US - all in people who had recently been in Wuhan.

But, even though the virus is spreading worldwide, Prof Kamradt-Scott says the domestic situation is more worrying.

"In each of the [other] countries where we've seen cases emerge, it's only been one or two, or four in Thailand," says Prof Kamradt-Scott.

"They're very small numbers of cases. It appears they have effectively been caught in time to prevent further transmission locally. So the bigger concern is within China."

Of the 571 cases reported by Thursday, 375 were in Hubei province, where Wuhan is the capital. But there were another 26 in Guangdong, 10 in Beijing, plus 38 possible cases in Hong Kong.

"If the virus is already there, and there's already local community transmission, then the measures in Wuhan are too late," says Prof Kamradt-Scott.

Prof Prokopenko agrees that the international response has been good. Passengers on the last plane from Wuhan to Sydney, for example, were greeted by biosecurity officials.

The problem, the professor says, is many people could have the virus and not even know it.

"There is a difference between infected and infectious," he warns.

"Infected people have a virus in their organism, but they are not yet infectious. They don't show symptoms. They look totally normal until they have already been in contact with other people."

The normal incubation period for flu, he says, is two or three days. But for a coronavirus, it could be five to six days, a week, or even longer.

That is - someone could have caught the virus last week, taken it across the world, infected others, and still not know they are ill.

"And when they do start showing symptoms, it may be confused with common cold or flu," says Prof Prokopenko. "That's the difficulty."

None of this means China is wrong to try to contain the virus. The WHO has praised their efforts, and there are some precedents for what experts call "social distancing".

In April 2009, Mexico City shut down bars, cinemas, theatres, football grounds, and even churches in an attempt to stop swine flu. Restaurants were only allowed to serve takeaway food.

"It did apparently slow the transmission of the virus in Mexico City, and helped authorities get a handle on the situation," says Prof Kamradt-Scott. "Did it stop it completely? No."

So overall, is the Wuhan shutdown worthwhile?

"China has only been reporting confirmed cases," says Prof Kamradt-Scott.

"On the basis of those numbers [571 cases, with 17 dead], if it was me, I probably wouldn't do it. But if there are thousands of suspected cases, then that would considerably change the equation."