Hong Kong's year in seven intense emotions

AFP

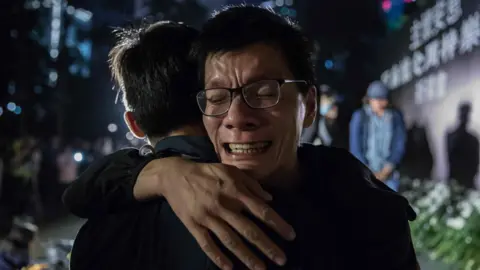

AFPNobody saw it coming. Hong Kong's year of protest and violence stunned everyone from observers to participants. What started the crisis was political - but emotion has fuelled it.

We picked seven to explain this year of tears, exhilaration, broken relationships and personal pride. Text by the BBC's Grace Tsoi, portrait photographs by Curtis Lo Kwan Long.

Saturday 30 March 2019 was the last normal day. Clear and sunny, it began like any other weekend in Hong Kong with its singular cocktail of frenetic leisure - family lunches, shopping late into the neon-lit night and cute selfies at every opportunity.

The next day, something more political began. A few thousand people marched through a dispiriting drizzle to protest against a proposal that would have allowed extradition to China: "With extradition to the mainland, Hong Kong becomes a dark prison," they chanted.

It didn't get much coverage then. But the city was listening.

Within six months, Hong Kong was a place of huge protest marches, street battles and an unapologetic police response of tear gas, rubber bullets, water cannon and live fire. Teenagers shot bows and arrows, the parliament chamber was vandalised, hundreds of young people now know how to make Molotov cocktails and start fires. But after the bill was withdrawn, the anger became more palpable if anything.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPolitics may have been the trigger, but reckless passion is the fuel and on display everywhere. Arguments have broken out on the street between strangers: one man was set on fire while arguing with anti-government protesters; a taxi driver full of rage ran his car through a group of protesters; a student fell to his death in unexplained circumstances; an elderly cleaner standing in the middle of the road gaping at a fight was hit by a stray brick careening through the air. He died.

It is a difficult thing to report dispassionately on the descent of your home, a city famous for stability, into a surreal dystopian vision. People are worried about China's domination but they are also worried about what violence has done to the fabric of society. It seems as if nobody is sleeping well any more.

The textbook factors of politics, economics, demographics, even democratic ideals, ideology and identity cannot fully explain this - but the emotional intensity generated by the interplay of it all completes the picture.

Even though the politics divides, the emotions are what the city shares - and these stories have helped me understand Hong Kong's fraught predicament.

BBC

BBC"I am now committed to the marriage for the sake of the family. He's no longer attractive to me."

BBC

BBCWhen Fiona met her husband at school, she knew she would marry him one day. Now, in their late 30s, they have a picture-perfect family with two children. But this is the year everything changed.

She is a protester. He is a policeman.

"I tell him I feel less love for him," Fiona says.

They didn't discuss politics when they were dating - there was little politics to discuss then.

It was only during the 2014 Occupy movement, which sought changes to Hong Kong's electoral system, that political differences emerged. She left home for the protest zone one month after she gave birth to their son, but felt wounded by the scorn of her husband.

Despite that, she believed that love could bridge any differences. That's not the case any more and the turning point for her - as for many others in Hong Kong - came on 21 July.

That night had seen protests erupt across the city. But as people headed home late in the evening another element entered the fray. In the rural district of Yuen Long, a large group of white-clad pro-government men, rumoured to be linked to triad gangs and armed with rods and poles, were waiting at the train station. They began beating people they believed to be protesters.

"I rushed out from the toilet with my phone in my hand. I told him the white shirts were beating up ordinary citizens in Yuen Long. He said he knew and went into the bedroom. He slept soundly that night, while I stayed wide awake."

STAND NEWS

STAND NEWSOutrage swept across Hong Kong and by the following morning there were accusations that the police had not done enough. Their denials were insufficient to prevent Yuen Long being used as proof that the police were not there for the people but for the masters. The next weekend of protest was one of the most violent seen up to that point.

Fiona's anger only grew as police became more heavy-handed. She and her husband began quarrelling over alleged police brutality.

Support for protesters, even as they went further in their violent action, is attested to by opinion polls. Protesters took out their rage on companies seen as pro-government: the MTR train operator saw stations and ticket machines vandalised, Chinese-owned ATMs were destroyed - this in a city famous for its respect for the rule of law. Yet the results of district election last month saw an overwhelming victory for pro-democratic figures.

Fiona's husband, though, was not swayed.

"Why is he so foolish? He thinks there's nothing wrong with the Chinese Communist Party and the extradition bill," Fiona says.

And so contempt crept into their relationship.

Her husband, however, still loves her very much. "He keeps sending me heart emojis. I used to reply to him with a heart but now I don't feel like doing it. And he keeps asking...

"I really want to love him again, but I can't."

She does acknowledge, though, that "this is his pride. This is his identity."

It is an acknowledgement needed by those in Hong Kong who support the police and the government. For them, one of the most unsettling things about Hong Kong's year is not confrontations between police and protesters, but the political fights that erupt on the street.

"They really treated us as if we murdered their fathers."

BBC

BBCJust over a month ago Crystal Chu, a 49-year-old businesswoman, arrived at the border station of Sheung Shui at the call of a pro-Beijing group, which planned to stage a protest. About 100 of them were soon outnumbered by pro-democracy protesters.

She was first pelted with eggs and projectiles and then she was hit in the head - she needed three stitches.

"That moment was horrifying. I feel like they came from hell," she says, at a loss to understand a dehumanising cycle of hatred against people simply expressing their views.

"They do this in the name of freedom. But it's just sheer violence."

The intensity of this hatred is being taken as a direct challenge to a system that has guaranteed stability, prosperity and a quiet life. For them, the pro-democracy movement is staffed by thugs with little understanding of political realities.

"Why don't they recognise themselves as Chinese? You can't deny this because we have black hair and yellow skin," Ms Chu says.

"Do you think Hong Kong can ever be separated from China?"

Few - on either side - have a clear grasp of the legal complexities of Hong Kong's special status, which makes safeguarding its fate all the more precarious. So the arguments end up being about ideology, identity and history. Ms Chu came from the mainland in her 20s. Many others of her generation, but born and bred in Hong Kong, will recall grandparents' tales about life in China. In the 1960s those grandparents may have swum over. Although they left China behind, it remains part of their identity.

The younger generation out on the streets does not share such memories - it is easier for them to disregard the older ties that bind. Their touchstones are globalised cultural memes of defiance: "If we burn, you burn with us" - they chant referencing The Hunger Games; Can You Hear the People Sing? they belt out from Les Miserables; Pepe the Frog, a symbol of the alt right movement, was also adopted - certainly unwittingly.

Ms Chu, though, feels alarm when strangers walk past quickly.

BBC

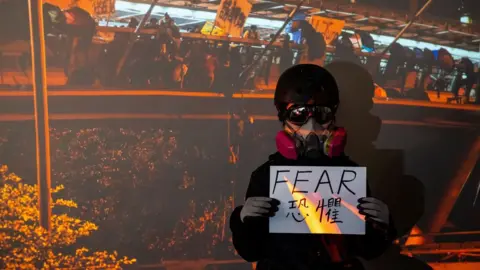

BBC"Many people always say those standing at the front are very brave. But it's not true. We are not brave. We are terrified."

BBC

BBCOver the past six months, Celine, a protester in her 20s, has attended almost every single march or rally going - and fought hard.

"Every time I am terrified. But I still do the same next time."

The fear she has on the frontline is, she says, dwarfed by her fear of what could come if she doesn't act. She is afraid of the way China has weighed in on Hong Kong's politics. After five booksellers who sold salacious books about Chinese leaders turned up in Chinese custody, after China interpreted Hong Kong's mini-constitution so a few pro-democracy lawmakers could be disqualified, she asked herself: if they can do this now, what might happen when that mini-constitution expires in 2047?

This is a fear shared by an entire generation. She will be in her 50s. Her generation will be parents. What will become of their children?

In the beginning, she only set up roadblocks using bricks. Soon her hands no longer shook when she threw petrol bombs.

With each passing month of exhausting and escalating protest, she watched both her resolve harden and her fear increase. The clashes bring thrills but everything changed for her during the siege of Hong Kong's Polytechnic University in November.

It was the site of a three-day showdown between police and protesters barricaded on the campus. Hours of intense fighting saw huge fires, petrol bombs, bricks and even bows and arrows being fired at police. Police struck back with rubber bullets, water cannon and tear gas so dense people could not see through the choking clouds.

SOPA Images

SOPA Images"I thought I might die inside."

"I saw a pool of blood," she says. "Many people were bleeding from their heads and they were crying."

She eventually managed to escape without being arrested.

Now, whenever she passes the university during bus rides she cries uncontrollably and finds it difficult to breathe.

Many young protesters acknowledge that their actions, while raising awareness, may only increase the likelihood of a more fundamental crackdown at some point. They know the risks but it is about balancing the probabilities of fears.

For those that speak out against protests - there is another, more deep-seated fear. They say that their Hong Kong, the safe prosperous society they built, is disappearing. Although staying silent was not ideal, they worry that this path is inevitable self-destruction from within rather than the feared assault from outside.

BBC

BBC"She is and always will be my daughter, and there is no way for us to cut ties with her."

BBC

BBCMr Tsang's mind went blank when he received a call one rainy October evening telling him that his daughter had been arrested in a protest. He was on a night shift as a security guard but hopped on a bus and arrived at the police station soaking wet.

It was after midnight when he finally saw his daughter Alice. The 16-year-old was followed by police officers and her hands were bound.

"We didn't need to speak," Mr Tsang says. "We could understand each other."

Alice has been charged with rioting, an offence which could lead to up to a decade in jail.

She's one of about 1,000 underage demonstrators who have been arrested since protests started in June. She says she isn't a frontline protester, but couldn't leave the protest site because every route was surrounded by police.

Reuters

ReutersOne of the most striking moments over the past few months was when school headteachers went to Polytechnic University to try to negotiate the release of their students. The first person to be shot by a live bullet was a secondary-school student. It is not just young people, but adolescents who have got involved. They may court dangerous thrills, but they believe they are safeguarding uncertain futures. Either way the trauma and the impact on this generation is yet to be properly understood.

In Mr Tsang's eyes, Alice is an ordinary teenager who loves make-up and shopping. She's also a daddy's girl who sometimes gets jealous of the family cat: "She says I love the cat more than her."

He has always known she was a protester: "I can't lock her up at home. No parent should do that."

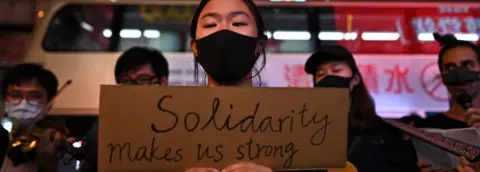

Yet he also witnessed a positive change in her because of the protests. She became more confident and made more friends. For a girl with depression and anxiety, that meant a lot. She is a living example of a culture of youth solidarity that has embodied these protests. They feel the older generation hasn't safeguarded their future, so it is in their hands - they have no options.

He still lets her join protests, but only those with police approval - he does not want to crush her ideals.

BBC

BBC"I never thought a photo would lead to such consequences."

BBC

BBCIn 2013, Lily Wong became a widow. Her husband died of a heart attack, leaving her with two young sons.

Three years ago she set up a snack shop as she didn't want to be on social welfare any more.

Business had been booming at Ms Wong's snack shop. Patrons travelled from other districts to taste her handmade steamed rice rolls, pudding cakes and herbal drinks. Recently, she thought that she might just be able save enough for a mortgage down payment.

But all that changed after she uploaded a photo to Facebook of her attending a pro-police rally. Ms Wong says she supports the police because it is the duty of police officers to maintain law and order.

"I don't regret uploading the photo because I just expressed my personal opinion."

- How is Hong Kong run and what is the Basic Law?

- A visual guide to how one peaceful protest turned violent

The backlash was immediate. Young people stopped coming to her shop and it has become the target of health and safety complaints.

In October, officials from different departments visited her shop almost every other day, she says: they came to investigate things like food hygiene and compliance with fire regulations. Apps in Hong Kong now identify outlets as either "blue" - sympathetic towards police - or "yellow", which means protest sympathisers.

During one such visit, she broke down in tears: "I was very emotional. I support my family and I want stability for them. But it felt like I was being pushed to the edge of a cliff."

Ms Wong mourns the loss of the old Hong Kong. "Hong Kong is a wonderful place. No matter one's education level, as long as one's willing to work, one will not starve," she says.

"Now, even eating is decided by colours."

She understands young people feel the need to fight for their future, but feels they are ignoring the cost of their actions and the fruits of the efforts of past generations.

"Society has been torn by politics, and I feel sad for it."

BBC

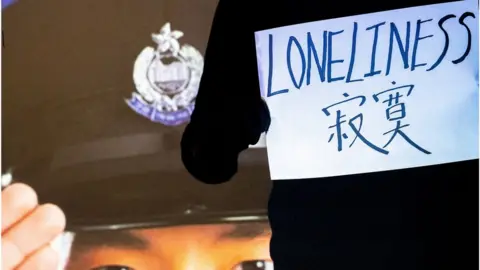

BBC"A senior officer said to me I was the only one who didn't hide my face... I wondered if he was hinting I wasn't a team player."

BBC

BBCIt was Derek's childhood dream to become a policeman. Officers always look sharp in cop movies and he truly believed he could help people.

But now he wants to quit.

Obedience is the most prized quality for police officers, as Derek has known from his first day - with little room for dissent.

For months, as violence has raged in Hong Kong, police officers have been wearing masks and their warrant cards have not been on display. Police say the masks are protective, but protesters say police are trying to conceal their identity to escape accountability.

"When I am on duty, I don't hide my face and I show my police number," Derek says. "This is a principle I adhere to." But this had implications for him on the front line when a senior officer questioned his motives.

PHILIP FONG

PHILIP FONGFor the police, this has all been genuinely tough. Officers have to put in at least 15 hours a day. Riot gear is heavy and it's exhausting to run around in the scorching sun. Policemen and their families have been doxxed - meaning their personal information has been leaked online - many feel this is just for doing their job. They face hatred just as much as they are accused of fuelling it.

Nonetheless, Derek feels there are no excuses for the unruly behaviour of police officers caught on camera beating protesters or opening fire: "Frontline officers have no restraint and use excessive force," he says.

He disapproves of unquestioning loyalty within the police force - but he thinks the same thing is happening among protesters. He can't accept any assault on people of different political persuasions.

"I asked my pro-protest friends if they would distance themselves from this - all of them said no," Derek says.

So he doesn't know where he stands in this new Hong Kong.

"He said I should follow Hong Kong's rules. He also told me to get back to where I come from."

For mainland-born Benjamin, the protests have finally made him consider himself a Hongkonger - after more than a decade.

On 16 June he spent five hours marching from Victoria Park to Admiralty by himself - a march that protesters said was attended by two million people.

"I am proud of this city," Benjamin says. He was touched by the resolve of the peaceful marchers.

But he is at odds with the community known as gang piao - (a Mandarin term which means Hong Kong drifters). These are the well-educated Chinese elites who move to Hong Kong. Every year, the government accepts 20,000 such "drifters", often scorned by locals for taking jobs.

"I can say 99 out of 100 drifters see their Chinese identity as unassailable," Benjamin says, and that they see a distinct Hong Kong identity as unacceptable.

Many mainlanders feel they have dedicated themselves to the city, but are suspected of just being "brainwashed" automatons. They cannot help but wonder if a touch of xenophobia is involved, even from people who they believe to be of their "own kind" - another example of how complex identity and allegiances are.

PHILIP FONG

PHILIP FONGAfter university, Benjamin was determined to leave mainland China. He valued personal freedoms and had a natural scepticism towards the authoritarian Chinese government.

But it has also been difficult for him to build friendships with locals because of differences in background and language. "We can... have dinner together," he says. "But we can't become good friends."

An August encounter with a pro-protest Uber driver sticks in his mind.

After a minor argument over a pick-up, "he said to me that he could tell I am not from here by my accent," Benjamin recounts.

When he and two friends were thrown out of the car, his friends seized the opportunity.

"They said, 'Don't you stand on their side? Oh, they don't see you as one of them?'"

He is now looking to move away from Hong Kong and China.

BBC

BBC"Students have lit fires and blocked roads, but this is nothing compared to the Cultural Revolution."

BBC

BBCThe city is living a double life. Protests at the weekend, business as usual on weekdays.

But Hong Kong has entered its first recession in a decade, with the number of tourists plummeting more than 40%.

Mr Chan, who has been working as a hawker for more than four decades, knows that tough times have come. Before the protests, he made more than HK$1,000 (about $130; £100) every day. "Now we only make a few hundred dollars."

His account is a corrective to the narrative that economic decline will infuriate Hongkongers - it hasn't yet. But shops are closing down and people are feeling financial pain.

Despite this, the 67-year-old remains unfazed, even though Kowloon has become a battleground.

A Guangzhou native, Mr Chan was witness to the Cultural Revolution - he once saw a peasant being beaten to death by children. He swam to Hong Kong in 1973.

Mr Chan doesn't blame the protesters for his losses.

"The future belongs to the youth, and they are fighting for things they want," he says. "We have enjoyed the most prosperous time, and we can only accept when things go downhill. It's as simple as that."

BBC

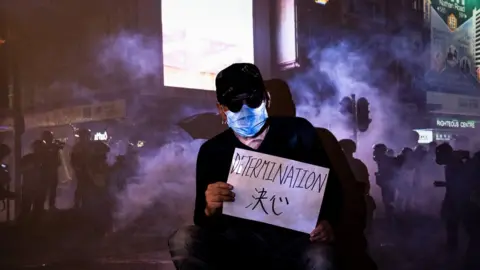

BBC"No matter how the protests will end, we will continue to fight next time."

BBC

BBCJames was in school for the 2014 Occupy Movement which eventually fizzled out - the protesters had lost.

On the last night before the clearance of the protest site, someone hung a banner with the words: "It's just the beginning."

"People said we would be back. In the beginning I wasn't that optimistic. I thought it would take at least 10 years," James says. "I didn't know it would happen so quickly."

James was in awe when a million took to the streets on 9 June. But he was especially touched by a July march organised by senior citizens who call themselves "the silver-haired". He did not know there would be so many older people who support the protests.

It was not the same experience at home - where he sees protesters as critical to defending Hong Kong's civil liberties, his parents think they are trouble-makers.

"My mother said it was right to beat people, and it's better to punish them all."

These differences have also upset his mother: "I have raised him... provided an education for him. The way he treats his elders makes me uncomfortable," she says. "He said I am not educated and know nothing.

"I don't care about which side he supports politically. But he can't treat his parents this way."

PHILIP FONG

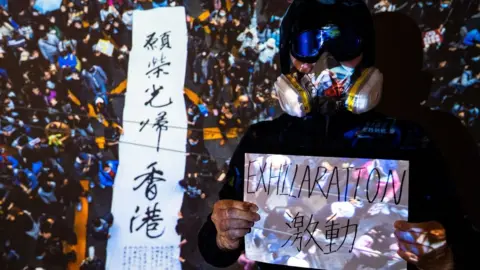

PHILIP FONGSeeing the older protesters was a moment of exhilaration for him, a bridge between generations.

These protests have been pivotal in cementing identity for thousands more like James across Hong Kong. It is no longer just a free-wheeling capitalist dream, where as long as you make money political apathy will rule the day. In just over 20 years it has seen one of the most rapid developments of group identity.

But it doesn't just go one way.

"China has developed well," says Lily Wong, who runs the snack shop. "Young people don't understand their identities and their origins."

She is one of those who feels the breath of China over their shoulder and is not chilled by it - but reassured.

They too have enjoyed being open about their feelings despite threats and condemnation from the many who support the cause of the protesters.

What nobody can do is tell us where Hong Kong goes from here. What they all know is that no matter what their view, they will fight with all their heart for what they believe is the best for the city.

Names have been changed, apart from Crystal Chu and Lily Wong.