What's behind China's space programme expansion

AFP

AFPChina is a relative late-bloomer when it comes to the world of space exploration.

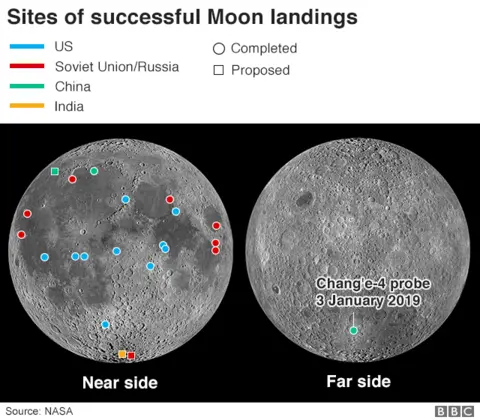

But just 15 years after it first sent an astronaut into orbit, China has become the first country to successfully land a robotic spacecraft on the far side of the Moon.

And in the next decades it plans not only to build a new space station, but also a base on the Moon and conduct missions to Mars.

Importantly, Xi Jinping, the country's most powerful leader since Chairman Mao, has thrown his support behind the "space dream" - and with it billions in investment. Chinese state media, meanwhile, have cast the "space dream" as one step in the path to "national rejuvenation".

So why are President Xi and China so keen to make their mark in space - and what does it mean for the rest of the world?

Sending a message

According to Prof Keith Hayward, a fellow of the UK's Royal Aeronautical Society, China is being driven by the same motivations as the US, Russia and others.

First, demand from the military, without which "you would not have had half the money going in".

Second, as "a good way to show off". "You could say that this is the space Silk Road - it demonstrates China is a force to be reckoned with," Prof Hayward notes.

Third, hitherto untapped resources which have the potential to make whoever finds them wealthy.

"It is the classic triad that has driven investment in space for the better part of 50 odd years," he told the BBC.

The landing of Chang'e-4 in January 2019 appears to sit comfortably within the second category - helping distinguish China as a force to be reckoned with, both globally and locally.

"It is something that is very, very good to have done," says Prof Hayward. "It says, 'we may not have put a man on the moon but we are pretty damn close to it'.

"It also sends signals out to their neighbours - it is a good way of showing soft power, with a little bit of hard."

China itself has been open about the value of space exploration in terms of increasing its standing on the world stage.

"Lunar exploration is a reflection of a country's comprehensive national power," Prof Ouyang Ziyuan - one of the country's top scientists - told China's official newspaper People's Daily back in 2006.

"It is significant for raising our international prestige and increasing our people's cohesion."

A new space race?

But it is not the prestige which is likely to be of concern to countries like the US.

Vice-President Mike Pence unveiled plans for a "US Space Force" in August 2018, saying it was needed because "our adversaries have transformed space into a war-fighting domain already". At the time, it was interpreted as a swipe at both Russia and China.

However, despite China's latest success and future plans, Prof Hayward doesn't seem to think the US needs to be worried.

"The US is still a big, big spender - not necessarily through Nasa [the US space agency], but through the Pentagon," he said. "I cannot see China being able to match that level of spending."

But is this a new space race? After all, the landing came just days after Nasa's New Horizons probe successfully carried out a flyby of an icy world some 6.5bn km (4bn miles) away. India, meanwhile, has announced it will send a three-member team into space for the first time in 2022. It seems like everyone is keen to make their mark.

So will China's advance worry other countries enough to cause them to adjust their future plans?

Unlikely, says Prof Hayward. "It is difficult to respond quickly - you are dealing here with some very long term plans."

What's more, Bernard Foing, executive director of the European Space Agency's International Lunar Exploration Working Group, noted that any advance was good for the wider world.

"China has shown a great advance and a will to collaborate with international partners," he said.

There is one country it cannot collaborate with, however: US counter-espionage legislation restricts Nasa from working bilaterally with Chinese nationals without express permission from Congress.

It has also been suggested that, despite appearing to aim to play catch-up with the US and Russia, China potentially doesn't view itself as being in a race with anyone.

"China is following its own motivations and interests rather than pacing its programme in competition with anybody else," John Logsdon, founder of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, told Wired magazine last year. "In my view, China is determining for itself what it wants to do, not in any formal competition with the quite uncertain plans of anybody else."

But, of course, space exploration is not just about political game playing.

There are also "genuine scientific objectives" to the Chang'e-4 mission, Dr Robert Massey of the Royal Astronomical Society pointed out.

Reuters

ReutersProf Ouyang also spoke of the country's scientific and technological goals in an interview with the BBC back in 2013.

"In terms of the science, besides Earth we also need to know our brothers and sisters like the Moon, its origin and evolution and then from that we can know about our Earth," he said.

And then there was the vast potential for resources, some of which could "solve human beings' energy demand for around 10,000 years at least".

Bringing them back, however, remains a challenge - but one which China will seek to solve: Chang'e-5 and 6 are sample return missions, delivering lunar rock and soil to laboratories on Earth.

Magpies and the Moon goddess

There are many elements of Chinese mythology present in China's space exploration program. to the Magpie bridge, China's relay satellite. Here's some background behind the names:

Chang'e (pronounced Chang-er): China's lunar probe is named after the Moon goddess and one of the most popular figures in Chinese mythology. She was a beautiful young woman married to a famous archer, Hou-yi, who managed to win an immortality potion. He decided not to take it as it was only enough for one, giving it to Chang'e for safekeeping. But one day a student of Hou-yi tried to steal the potion. Unable to defeat him, Chang'e drank the potion and floated to the Moon, where she still lives. Hou-yi was heartbroken and every year when the Moon was at its fullest, he would lay out her favourite food in tribute to her - an annual tradition across China ever since.

Jade rabbit: China's Moon rover is named after Chang'e's only companion on the Moon

Magpie bridge: China's relay satellite takes its name from the story of a goddess's daughter who falls in love with a poor farm hand. They get married and eventually have children. But when the goddess finds out, she's furious - and banishes them to different sides of the Milky Way. Feeling sorry for the grieving couple, magpies decide that once a year, they would form a bridge to connect the two lovers. This day is celebrated every year in China, their own version of Valentine's Day.