Zhao Kangmin: The man who 'discovered' China's terracotta army

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen archaeologist Zhao Kangmin picked up the phone in April 1974, all he was told was that a group of farmers digging a well nearby had found some relics.

Desperate for water amid a drought, the farmers had been digging about a metre down when they struck hard red earth. Underneath, they had found life-size pottery heads and several bronze arrowheads.

It could be an important find, Zhao's boss said, so he should go and have a look as soon as possible.

A local farmer-turned-museum curator in China's central Shaanxi province, Zhao - who died on 16 May at the age of 81 - had an inkling of what he might find. He knew figures had in the past been dug out of the earth in the area near the city of Xian, home to orchards of persimmon and pomegranate trees, and not far from the tomb of China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang.

A decade earlier, he had personally uncovered three kneeling crossbowmen. But he had never been certain that they dated back to the rule of the emperor - who unified the Chinese nation for the first time under the short-lived Qin dynasty (221-206 BC).

But what Zhao was about to find would surpass anything he could have imagined. The farmers, it would turn out, had stumbled upon one of the most stunning archaeological finds of the 20th Century: a terracotta army estimated at 8,000-strong, crafted on an industrial scale 2,200 years earlier to defend the emperor in the afterlife. A ghost army, complete with horses and chariots, hidden underground and never meant to be seen by the living.

Zhao headed to the location of the find with a colleague. "Because we were so excited, we rode on our bicycles so fast it felt as if we were flying," he would later write in a 2014 essay. As he arrived, Zhao told the British historian John Man: "I saw seven or eight pieces - bits of legs, arms and two heads - lying near the well, along with some bricks."

John Man

John ManHe said he immediately realised these were likely the remnants of Qin-era statues. The farmers - who had made the find weeks earlier and already sold some of the bronze arrowheads for scrap - were told to stop their work immediately. The relics were collected and brought to the museum on the back of trucks. Zhao began laboriously putting the fragments together. Some, he later said, were the size of a fingernail.

Finally, after three days of work, two imposing terracotta warriors stood before him - each 1.78m tall. But while Zhao was buoyed by this incredible discovery, he was also nervous. China in 1974 was in the closing stages of Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution - under which the fearsome Red Guards sought to destroy old traditions and ways of thinking to "purify" society.

Daniele Darolle

Daniele DarolleZhao, as Man recounts in his book The Terracotta Army, had personally been subject to a "self-criticism" session in the late 1960s, as a person "involved with old things". So now although the worst excesses of that period were over, Zhao was worried what might become of the statues.

He "decided to keep it secret", restore the artefacts, "and then wait for the right opportunity to report it".

But those plans would be scuppered by a young journalist from state news agency Xinhua, who was visiting the area when he came across the statues.

"He asked: 'This is such a huge discovery. Why aren't you reporting it?'" Zhao wrote.

To which the archaeologist replied: "Even I don't know how to make sense of this. How could I report it?"

Ignoring his pleas, the journalist publicised the find, and word made its way to the very top of the Communist Party leadership. Zhao's fears that the relics could be smashed for political reasons, however, proved unfounded.

The authorities in Beijing decided to excavate the site and within a few months more than 500 warriors had been uncovered.

As the work continued, the extraordinary scale of what the First Emperor - a ruthless man who defeated six warring states to unite China under an imperial system that continued until 1912 - had commissioned became clear. He is said to have ordered the subterranean project - which in total covers some 56 sq km - soon after ascending to the throne at 13 years old.

The thousands of warriors were placed in battle formation, ready to defend their emperor from whatever might await in the afterlife. The workmanship was detailed, with dozens of different types of heads, and in the burial pits were 100 chariots and tens of thousands of bronze weapons.

The actual tomb of Emperor Qin Shi Huang remains sealed. There could be thousands of precious artefacts inside but the risks of opening the tomb, and irreparably damaging what may lie inside, means the Chinese government has held off so far.

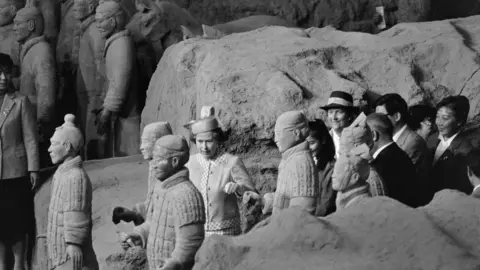

In 1975, a year after the excavations began, a decision was made to open a museum at the site. And as digging continued in the coming years, word spread about the scale of what had been found. Foreign dignitaries and some tourists began to visit. Zhao was there and lapping up the attention, says Prof Dame Jessica Rawson of the University of Oxford, who specialises in Chinese art and archaeology and visited the sites in the early 1980s.

"By the time I met him everyone was showing him great respect and he was very much sort of enjoying the esteem associated with the terracotta warriors," she said.

But the professor added: "I'm not sure how he or the Chinese authorities viewed it at the time. They were probably not expecting the acclaim and success that it has later enjoyed."

AFP

AFPIt did take some years for the site to receive widespread global recognition. It was given Unesco World Heritage status in 1987, with the UN cultural body describing the warriors as "masterpieces of realism".

Today, the site is widely recognised as a Chinese national treasure. But there is a sense that Zhao's personal role in the discovery was never fully recognised. He is by no means well-known in China.

Read about other notable lives

Instead, one of the farmers - Yang Zhifa, whose shovel is said to have unearthed the first artefact - is described to visiting tourists as the person who discovered the warriors.

For years he sat in the Museum of the Terracotta Warriors and Horses, quietly and unsmilingly signing books. It was he, not Zhao, who travelled abroad to tell his story. In 1998, when then US President Bill Clinton visited, it was Yang who shook his hand.

John Man

John ManA few years ago he admitted that he didn't go and see the restored army until 1995, when the museum gift shop manager asked him to sign books.

"He said he would pay me 300 yuan a month. I thought 'that's not bad', so I came," he told the China Daily. Three other farmers would later join him, and their pay was tripled. But all complained they were never rewarded properly for their find, and in fact had their land seized to make way for the museum.

Three of the original group of seven farmers died in terrible circumstances. One hanged himself in 1997, and two others died in their early 50s, penniless and unable to pay for medical care, according to the South China Morning Post.

A local guide who brings tourists to see the warriors, Liu Guoyang, had not even heard of Zhao Kangmin. But he said imposters posed for visitors, pretending to be Yang Zhifa or one of the other farmers.

AFP

AFPZhao was furious when, in 2004, the four surviving farmers officially asked to be registered as the men who had discovered the warriors. They didn't receive a response.

"What they want is money," Zhao told the China Daily. "Seeing doesn't mean discovering. The farmers saw the terracotta fragments, but they didn't know they were cultural relics, and they even broke them.

"It was me who stopped the damage, collected the fragments and reconstructed the first terracotta warrior," he said. If he hadn't have turned up, he told John Man, "it would have been a disaster".

Wu Yongqi, head of the Museum of the Teracotta Warriors from 1998-2007, agreed that Zhao, who he described as a simple but kind man, was the person who "recognised the significance and true value of those warriors".

Without him, Mr Wu said, the extraordinary find might have been delayed for years.

Unlike the farmers, who signed books for hordes of tourists at the main warriors' museum, Zhao remained at the much smaller Lintong county museum. Even in his final years, he could be found sitting next to some warriors he had restored, wearing a trilby hat and chatting to curious visitors.

Although he never achieved fame or fortune, Zhao seemed content with the recognition he did receive - proudly saying that during the initial excavation an envoy from Beijing had told him that he had "made a very big contribution to the country". In 1990, he was personally acknowledged by the State Council and given a special pension. He is survived by a wife and two sons.

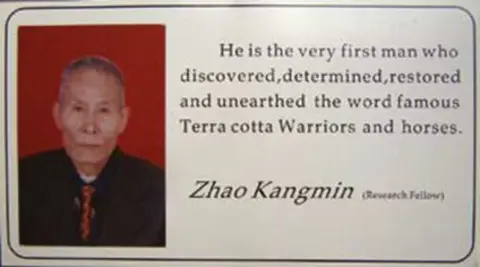

Zhao's view of his own position in Chinese history - no matter what others might say - was clear. At the Lintong museum, he would sign postcards and books for tourists with an extravagant description: "Zhao Kangmin, the first discoverer, restorer, appreciator, name-giver and excavator of the terracotta warriors."

Additional reporting by Yashan Zhao, BBC Chinese