Five ways China's past has shaped its present

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTo understand today's headlines about China's approach to issues such as trade, foreign policy or internet censorship, turn to its past.

The country is perhaps more aware of its own history than any other major society on earth. That remembering is certainly partial - events like Mao's Cultural Revolution are still very difficult to discuss within China itself. But it is striking how many echoes of the past can be found in its present.

Trade

China remembers a time when it was forced to trade against its will. Today it regards Western efforts to open its markets as a reminder of that unhappy period.

The US and China are currently in a dispute over whether China is selling into the US while closing its own markets to American goods. Yet the balance of trade hasn't always been in China's favour.

In Beijing, there are long memories of a period, nearly a century and a half ago, when China had little control over its own trade.

Britain attacked China in a series of Opium Wars, starting in 1839. In the decades that followed, Britain founded an institution called the Imperial Maritime Customs Service to fix tariffs on goods imported into China.

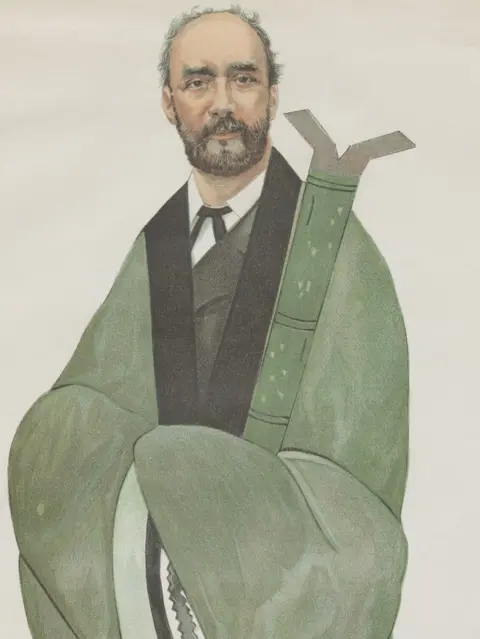

It was part of the Chinese government, but it was a very British institution, run not by a mandarin from Beijing, but a man from Portadown.

Getty Images

Getty Images

Sir Robert Hart ended up becoming inspector-general of the Customs of China, which became a fiefdom for Brits for a century afterwards. Hart was honest and helped to generate a great deal of income for China.

But the memories of that time still rankle.

It was very different in the Ming dynasty, in the early 15th Century, when Admiral Zheng took seven great fleets to South East Asia, Ceylon and even the coast of East Africa to trade and show off China's might.

Alamy

Alamy Zheng He's voyages were partly about making an impression. Few other empires could boast the massive fleets that it sent out across the oceans, and it was also an opportunity for strange and wonderful items be brought back to Beijing - such as China's first giraffe.

However, trade was also important, particularly in other parts of Asia. And Zhen could, and did, fight when he wanted to, defeating at least one ruler of Ceylon. Yet his voyages were a rare example of a state-driven maritime project. Most of China's overseas trade for the next few centuries would be unofficial.

Trouble with the neighbours

China has always been concerned to keep states on its borders pacified. That's part of the reason it deals so warily with an unpredictable North Korea today.

This is not the first time that China has had problems with those on its borders.

In fact, history reveals it has had worse neighbours than North Korean leader Kim Jong-un, who recently made a surprise visit to Beijing, his first known foreign trip since taking office in 2011.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring the Song dynasty in 1127, a woman named Li Qingzhao fled her home in the city of Kaifeng. We know her story because she was one of China's finest poets, and her works are still widely read. She went on the run because her state was under attack.

A people from the north, the Jurchen, had burst into China after a long period of uneasy alliance with the ruling Song dynasty's emperor. The elite of China's civilisation had to spread themselves across the country as cities burned.

Li Qingzhao saw her beloved art collection scattered between various cities. Her dynasty's fate was an object lesson that appeasing the neighbours may work for only so long.

For some time, the Jin dynasty ruled Northern China, and the Song founded a new realm in the south. But in the end, both fell to a new conqueror, the Mongols.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The shifting lines on the map show that the definition of China has changed over time. Chinese culture is associated with certain ideas such as language, history and ethical systems like Confucianism.

However, other peoples, including Manchus and Mongols from the north, have taken China's throne at various points, ruling the country using the same ideas and principles upon which their ethnic Chinese counterparts relied.

These neighbours did not always stay put. But sometimes they embraced and exercised Chinese values just as effectively as the people from whom they took them.

Information flow

Today China's internet censors politically sensitive material, and those who utter political truths deemed problematic by the authorities may be arrested or worse.

The difficulty of speaking truth to power has long been an issue. China's historians have often felt they had to write what the state wanted rather than what they thought was important.

But Sima Qian - often dubbed China's "grand historian" - chose a different path.

Alamy

Alamy

The author of one of the most important works chronicling China's past, in the 1st Century BC, he dared to defend a general who had lost a battle. In doing so he was held to have snubbed the emperor, and was sentenced to castration.

Yet he left behind a legacy which has shaped the writing of history in China to this day.

Find out more:

- Professor Rana Mitter presents Chinese Characters on BBC Radio 4, a series of 20 essays exploring Chinese history through the life stories of key personalities

- You can listen to the programmes on the BBC Radio 4 website, or download the Chinese Characters podcast

His Records of the Grand Historian (Shiji) mixed different types of sources, critiqued figures from the historical past, and also used the techniques of oral history to find out directly from participants what had actually happened.

All of this was a very new way of doing history, but it set a precedent for later writers: if you were willing to risk your safety, you could write history "warts and all", rather than censoring yourself.

Freedom of religion

Modern China is much more tolerant of religious practice than in the days of Chairman Mao's Cultural Revolution - within limits - but past experience makes it cautious about faith-driven movements which could potentially spiral out of control and pose a challenge to the government.

Records show that openness to religion has long been part of Chinese history.

Alamy

Alamy

At the height of the Tang dynasty in the 7th Century, the Empress Wu Zetian embraced Buddhism as a way of pushing back against what she must have regarded as the stifling norms of China's Confucian traditions.

In the Ming dynasty, the Jesuit Matteo Ricci arrived at court and was treated as a respected interlocutor, although there was perhaps more interest in his knowledge of Western science than his slightly wan attempts to convert his listeners.

But faith has always been a dangerous business.

In the late 19th Century, China was convulsed by a rebellion started by Hong Xiuquan, a man who claimed to be Jesus's younger brother.

The Taiping rebellion promised to bring a kingdom of heavenly peace to China but actually led to one of the bloodiest civil wars in history, killing as many as 20 million people, according to some accounts.

Government troops initially failed to tame the rebels, and had to allow local soldiers to reform themselves before they eventually put down the Taiping with great cruelty in 1864.

Alamy

Alamy

Christianity would be at the centre of another uprising some decades later. In 1900, peasant rebels calling themselves Boxers would appear in north China, calling for death to Christian missionaries and converts, the latter being characterised as traitors to China.

At first, the Imperial Court backed them, which led to the death of many Chinese Christians, before the uprising was eventually put down.

Through much of the following century, and to the present day, the Chinese state has veered between tolerance of religion, and the fear that it may upend the state.

Technology

Today China seeks to become a world hub for new technology. A century ago it went through an earlier industrial revolution - and women were central to both.

China is a world leader when it comes to artificial intelligence (AI), voice recognition, and big data.

A large number of the smartphones around the world are built with Chinese-made chips. Many of the factories which manufacture them are staffed by young women who often endure horrific conditions of work, but who are also finding a place in the industrial market economy for the first time.

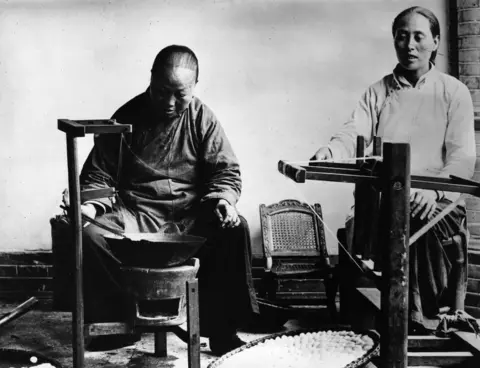

They have inherited the experience of the young women who came 100 years ago to the factories that sprang up in Shanghai and the Yangtze delta.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThey were not making computer chips, but silk and cotton threads.

Work was hard and likely to cause lung disease or physical injury, and conditions in the workers' dormitories were spartan.

Yet the women also recalled the pleasure of having their own wages, however, small, and the ability to visit a fair or theatre on a rare holiday.

Some made the journey to look - probably not buy - at the shiny new department stores in central Shanghai, one of the ultimate symbols of modernity.

Today, on Nanjing Road in that city, you can still see China's new working and middle class enjoying a wide range of consumer goods as part of China's contemporary tech-driven economy.

The view from future historians?

We are living through another significantly transformative era for China. Future historians will note that a country that was poor and inward-looking in 1978 became - within a quarter of a century - the second biggest economy in the world.

They will also note that China was the most important country to push back against what had seemed like an inevitable tide of democratisation.

Perhaps other factors such as the one-child policy (now ended) and the use of AI surveillance may catch future writers' attention. Or maybe it will be something else to do with the environment, space exploration or economic growth, which is not yet even obvious to us.

One thing is almost certain - a century from now, China will still be a place of fascination for those who live there and those who live with it, and its rich history will continue to inform its present and future direction.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Prof Rana Mitter is professor of the History and Politics of Modern China at the University of Oxford, and is director of the University China Centre.

Edited by Jennifer Clarke