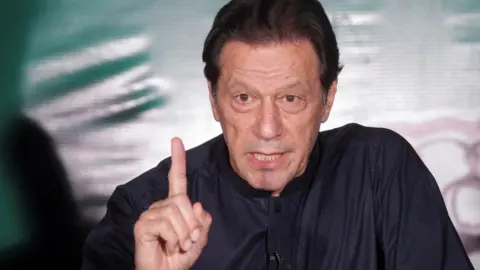

Imran Khan: How Pakistan ex-PM plans to win an election from jail

BBC

BBCFrom prime minister to prison in less than two years, Imran Khan and his party have fallen dramatically from political grace.

But the PTI says it has not given up its belief that it can win this week's general election in Pakistan, despite its founder being jailed in cases he says are politically motivated, and barred from running for office.

The party is aiming to overcome the authorities' crackdown with the help of a social media fightback - and new candidates, many of them untested.

Rehena Dar is being swept along the back roads of Sialkot, past the posters of her face plastered on the narrow street corners of this city in Punjab province. Her way is cleared by the sound of beating drums as rose petals shower her from above.

If becoming a politician unexpectedly in her 70s has taken her by surprise, she doesn't show it for a second. The fears which have driven many of her fellow candidates underground or out of politics seem to have been shrugged off.

"It is very good that the proud sons and daughters, brothers and mothers of my city Sialkot are standing with me," she shouts with the confidence of someone who has worked the electorate for years.

"I am with Imran Khan and I will stay with Imran Khan. If I am left alone in public, I will still carry Imran Khan's flag and take to the streets."

A quick glance around certainly indicates that is true. The small crowd that has gathered around Mrs Dar hold Imran Khan's image aloft, while flags for his PTI flutter overhead.

And yet, Mrs Dar is not a PTI candidate. Instead, she - like all their candidates - is technically an independent, following the electoral commission's decision to strip the PTI of its cricket bat symbol.

It may seem a small decision, but in a country with a literacy rate of 58%, having a recognisable symbol the candidates use on the ballot paper is crucial. Now each candidate has their own alternative symbol; Mrs Dar's is a baby's cot, others have items ranging from a kettle to a saxophone.

The decision is just one of the myriad barriers that the PTI says have been placed in its way as it gears up for the election on 8 February.

But it has continued to fight. Whether it be candidates pounding the streets like Mrs Dar, or technology that transports a leader from a jail cell to the head of a rally, it's proving it's willing to throw everything it has into this battle.

EPA

EPADuring the last election it was Mrs Dar's son, Usman, leading the group through Sialkot. He was a senior PTI leader and served as a special adviser on youth affairs under former PM Imran Khan.

But in early October, after disappearing for three weeks according to his family, he appeared on television to say that Imran Khan had been the "mastermind of the 9 May riots".

Nationwide protests, some of which became violent, erupted on that day last year after Imran Khan was arrested. Hundreds of Khan's supporters were arrested, accused of being involved in attacking military buildings, including the residence of the most senior military official in Lahore.

Khan was released, but the crackdown on his party continued.

In the weeks and months after the protests, politicians in his party announced their resignation from the PTI or from politics altogether. They included many of his senior leadership, which the authorities argued were an indication that Khan's old supporters didn't want to be associated with a party that bore the responsibility of the unrest.

The PTI said the resignations were forced.

Whichever is true, Mrs Dar was unimpressed.

"When Usman Dar gave his statement, I did not agree to it," says Mrs Dar. "I told him that it would have been better if my son had returned dead. You have made a false statement."

Mrs Dar's overt style of campaigning, however, is not a possibility for all the PTI's candidates.

Some candidates have kept campaigning despite being in prison; provided they have not been convicted of a crime, they are free to stand for election from behind bars.

Others have avoided the police altogether and are running their campaigns from hiding.

Atif Khan was a provincial minister in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa in the north of Pakistan. Now, as part of his campaign, he appears on video broadcasts on three-metre screens his team drives around his patch, parking up in town squares to address PTI supporters.

This is the only way he can take his message to voters, he says, because he has been in hiding since May. The authorities say he is a wanted man. He believes he wouldn't get a fair trial.

"It's a totally different experience, not amongst the crowds, not on stage, not amongst people, but we are trying to manage it," Mr Khan told the BBC.

"The biggest support base of PTI is the young voter. They are using digital media, mobile phones, that's why we thought we should be more engaged with them through it. That is the only thing we can do, we can campaign through digital media."

Technology has been crucial for the PTI's campaign.

The party's official X, Instagram and TikTok pages each have several million followers, more than the other two main parties - the PPP and PML-N - combined. Imran Khan is the only leader of the three parties to have a personal account on each of those three platforms too, which means their message is going direct into people's hands.

Reuters

ReutersThere have also been efforts to use tech to try to help voters know which candidate is PTI-backed. Without the uniting image of the cricket bat, the PTI have developed a website where voters can put in their constituency and discover their PTI-backed candidate's symbol.

Another issue arose when it came to arranging rallies. In Pakistan, politics is tied to personality. Imran Khan - the beloved cricketer-turned-politician - was arguably one of the biggest, able to draw thousands to his rallies.

But he now sits in jail, where he has been since August and looks likely to be for the next 14 years following three sentences handed down this week.

The party also says it has faced issues organising rallies. In late January, police used tear gas to disperse a crowd of hundreds of PTI supporters in Karachi. The authorities said that they did not have the right permissions to gather.

EPA

EPAThe PTI have said that this is just the latest example of how they have been stopped from campaigning. Every candidate's campaign team the BBC spoke to talked about their supporters being intimidated. The PTI have alleged that there has been a campaign of harassment, abduction, imprisonment and violence against them to stop them from running.

"We find these allegation baseless and absurd," caretaker minister of information Murtaza Solangi told the BBC. "Yes people have been arrested, but those arrests were made because some related to 9 May incidents and some involved other criminal cases.

"However they [the PTI] are free to express their dissent and allegation even if they are baseless. The media carries them. At the same time they have other legal options available, including the highest courts of the land."

The solution to these problems? Virtual rallies.

"It's cheap, it's safe and it's fast," Jibran Ilyas, head of PTI social media, told the BBC by phone from his base in Chicago. "It's a little less impact maybe from the physical rallies, but we were trying to get our message out.

"We've never had a political rally without Imran before," Mr Ilyas said. Would one without him work? They weren't so sure.

The problem is, he says, "people are longing for Imran Khan's message".

So how to get the message out?

In December, they used AI to generate a speech for an online rally.

There are limitations. According to internet monitoring group Netblocks there was nation scale disruption across different platforms in Pakistan on several occasions that coincided with some of these PTI rallies.

"Only about 30% of Pakistan's population are active social media users. So that suggests that as good as the PTI is at getting the word out on social media there will be inherent limits to their reach with their online campaigning," says Michael Kugelman, director of the South Asia Institute at the Wilson Centre think tank in Washington.

This has, of course, been seen before - notably, during the last election when Nawaz Sharif was behind bars.

"If this all sounds the same, that's because it is; it's just that the players have changed," says Mr Kugelman.

Reuters

ReutersHe, like most political analysts, sees the hand of Pakistan's powerful military behind this change in fortunes - the same military that many see as being Imran Khan's initial ticket to power.

"The PTI had electoral support in 2018, but they clearly benefitted from electoral engineering influenced if not undertaken directly by the military

"There were extensive levels of repression and manipulation. There were arrests of members of the PML-N party, there were prison sentences that were announced close to the election, including Nawaz Sharif getting a 10 year jail sentence."

That said, Mr Kugelman thinks this is different to recent times.

"I would argue that the playbook is the same, but this time around the intensity is greater. The numbers of leaders and supporters that have been arrested and jailed is higher than recent elections.

"This time family members have been caught up in this. That's not unprecedented but it stands out in what we have seen in more recent elections."

The PTI have tried to use each blow to Imran Khan or to its campaign as fuel, but will that work?

Pakistan's TV channels are full of election rally coverage of Khan's rivals Nawaz Sharif on stage for the PML-N, or Bilawal Bhutto for the PPP. The main coverage the PTI has received in the week running up to the election is about their founder's prison sentences.

Mr Kugelman argues that many voters could feel like there's no point in voting as they feel there is no way the PTI could win.

"The question for the PTI leadership is how to inspire a large support base to come out and vote despite everything that's happening to Khan. There are some in the PTI who think if they do get out there and voter turnout is high enough they could pull off a miracle and win."