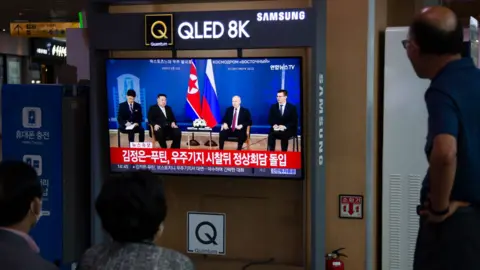

Kim Jong Un-Putin talks: What do the optics tell us?

Reuters

ReutersThey strolled side by side through the gleaming space centre - stopping to peer into the pit from where rockets blast into space.

At their lavish banquet, they drank Russian wines and toasted the embrace of their two pariah states.

And before leaving, they swapped guns as gifts - model rifles from each others' munitions lines.

The optics of Kim Jong Un and Vladimir Putin's date in eastern Russia clearly underscore a relationship that is being strengthened in wartime.

It isn't over yet, with the North Korean leader spending several days touring shipyards, aircraft factories and other military sites before he returns home.

There had been great anticipation in the lead-up - with global media rapt as Kim trundled for hours in his armoured train over the border.

He kept the West guessing for nearly 40 hours before reaching the Vostochny Cosmodrome - a space base in a far-flung eastern corner of Russia. Even then, it was unclear what exactly the pair would be meeting to talk about - with White House warnings last week that the North could sell arms to Russia sparking alarm.

Putin had sent ahead a welcome party to greet Kim as his train rolled onto the space base's tracks. A red-carpeted, balustrade staircase was also erected mid-air, waiting for the train to pull in and for the North Korean leader to step out.

KCNA

KCNAPutin was waiting in front of the centre when Kim drew up in his limousine. There, before flashing cameras, the two leaders shook hands - the pictures beamed out immediately by state media.

Both leaders know the power of showmanship, but the Supreme Leader of North Korea, as Kim is known, is particularly a fan of ceremony. He is third in a dynasty of supreme leaders "who have generations of mythology constructed around them", says Sarah Son, a North Korea expert at the University of Sheffield.

"It wouldn't do to be seen as a run-of-the-mill, limited term state leader by domestic audiences, who will be seeing this journey and parts of the meetings on television and in the newspaper.

"It's very important for Kim to have one-to-one meetings with leaders of other countries so that all eyes are on him, making North Korea appear as a more significant global player than it actually is.

"Sanctions of course remain extremely tight and Russia's need for arms presents an opportunity to achieve two complementary aims: income for the North Korean state and evidence that Kim is worthy of the attention of the leader of a major global power."

About an hour before the two leaders met, Pyongyang had also fired off two ballistic missiles - the first launched without the leader at home.

"The summit defiantly linked pariah state behaviour in Europe and Asia," says Leif-Eric Easley, a professor at Ewha University in Seoul.

KREMLIN/REUTERS

KREMLIN/REUTERSBut beyond the spectacle and bombast, observers question whether the meeting achieved any concrete deals. Little was revealed publicly.

"As of now, it appears that there have been no substantial developments in the public domain," says Fyodor Tertitskiy, a North Korean military researcher at Kookmin University in Seoul.

"We observed a two-fold event - a grand spectacle primarily designed for foreign audiences and undisclosed agreements behind closed doors, the significance of which remains uncertain."

No detail was revealed of the feared arms deal the West is concerned could boost Russia's fight in Ukraine.

And no word was mentioned either of certain gains for North Korea - of food aid, economic help or military and technology sharing, the things that Kim would have wanted say analysts.

Instead the only known advance appears to be Putin hinting he could potentially help with Kim's space and satellite goals.

That's where the choice of venue was noticeable analysts say. Both leaders travelled long distances to get to the space port on the other side of the country from Moscow.

Reuters

Reuters Reuters

ReutersBut meeting at the site provided significant optics for Putin, analysts say.

First, his offer of space assistance could be argued as being within the acceptable limits of what Russia can give North Korea.

Pyongyang has failed twice this year to get a spy satellite into space - their technology is still decades behind Russia's.

And for Moscow, helping put a satellite in space so the North can watch its enemies is vastly different to the Kremlin aiding a nuclear and missiles programme banned by the UN Security Council.

But the problem remains that we don't know what was actually promised to the North.

Pyongyang has nuclear warhead-topped intercontinental ballistic missiles which in theory could reach the US. They currently don't- because the North in part hasn't worked out how to keep them from frying as they fly through space.

Russia and the US however know how to protect their missiles- from the same technology they use to protect their satellites. If Moscow has shared this technology with Pyongyang, the US could potentially be in striking distance.

As such, the meeting this week at the spaceport is "equivalent to Putin thumbing his nose at UN Security Council Resolutions", says Prof Easley.

"This should be a wake-up call to all other UN member states about the need to redouble efforts at enforcing sanctions on Pyongyang," he said.

EPA

EPABut there remains significant doubt over whether Russia would share any of its space jewels, or even sees the North's arms as anything more than a back-up supply.

"Even with regards to the satellite technology, Putin's statements were cautious, not an explicit commitment to provide assistance but rather a strong implication that it may be considered," says Mr Tertitskiy.

He also points out the near non-existent money flows between the two - despite the rhetoric surrounding weapons, trade remains near zero according to South Korean estimates. North Korea remains reliant on China for over 95% of its trade income.

"This leaves us uncertain whether this summit will yield any more concrete results than the fruitless 2019 meeting did," he says, referring to the last time the two leaders met.

KCNA

KCNAIt has been four years since that huddle, and for Kim this rare trip shouldn't be underplayed, analysts say. This was his first foray abroad in four years, as his reclusive state also begins to re-open to the world post pandemic.

Putin made sure that he would be treated handsomely, observers say.

The meeting could have just been held in Vladivostok, on the sidelines of the Eastern Economic Forum, Putin's signature Asia-facing platform which has previously been attended by Chinese and South Korean leaders.

Instead, he chose to give Kim centre stage, at a different venue altogether - bringing out the red carpet, the banquet, the brass marching band - and then also making the trip to meet him there.

"It is a sign of respect for Kim. This could be seen as a gesture to ensure Kim feels valued," says Mr Tertitskiy.

But equally, he says, it's also about the message being sent to the West - elevating the perception of their relationship even when the details are scant.

But in this relationship, it's crucial to focus on what the two sides actually do, he says.

"Both Kim and Putin are adept at employing deception. Once again, it's imperative to scrutinise their concrete actions rather than their words."