From trauma to training - new lives for North Korea’s defectors

Unification Ministry

Unification MinistryAbout two hours' drive from the South Korean capital, Seoul, in a rural setting of wooded hills and rice paddies, is a complex of buildings that look out of place.

Towering over the surrounding countryside, these multi-storey structures are surrounded by a high fence and guarded gate. The compound is isolated, secure and private.

Part training-hub, part medical facility, part re-education centre, this is where North Korean defectors are sent for three months when they arrive in South Korea.

Its name is Hanawon, or to give it its full title, the Settlement Support Centre for North Korean Refugees.

The number of North Koreans making the difficult and dangerous journey to South Korea - risking possible death if they are caught - to escape poverty and repression has fallen significantly in recent years.

A decade or so ago, nearly 3,000 arrived each year. That figure dropped to around 1,000 in the years that followed and then to below 100 during the pandemic, when North Korea sealed its borders.

Despite that, South Korea has reaffirmed its commitment not just to keeping Hanawon open, but to expanding its facilities.

Unification Ministry

Unification MinistryThe government in Seoul believes that as Covid controls are relaxed in North Korea, more of its people will be able to flee. If that happens, Hanawon will again fill up.

Unification Minister Kwon Young-se said South Korea needs to prepare to greet these new arrivals.

"We need to think of defectors not as aliens, but as neighbours whose hometown is in the North," he said.

With its hedges, flowers and manicured trees, Hanawon appeared welcoming in the summer sun on Monday, when the South Korean government gave journalists a rare glimpse inside the facility.

We were shown around a training centre, where North Korea defectors are offered 22 courses, in subjects such as hair and beauty, baking and clothes making.

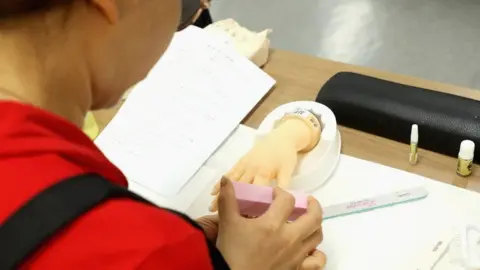

One room has been made to look like a nail parlour, where defectors learn the delicate art of the manicure. They use model hands to practice painting, polishing and filing.

Unification Ministry

Unification Ministry The delicious smell of baking fills the air; it has drifted down from a cookery class next-door.

Other courses are aimed at helping the North Koreans adjust to life in a country that is, in terms of technology, decades ahead of where they came from.

One classroom is set up like a shop selling high-tech gadgets. Tablets, smartphones and computers have been put on display.

While the floor of another building looks like a modern hospital. There is a small ward, consulting rooms and doctors walking around in white medical coats.

It is not just the physical needs of the North Koreans that are catered for; many arrive with severe psychological problems that need urgent attention.

Dr Jeon Jin-yong is a psychiatrist who has worked at Hanawon. He has heard terrible tales of trauma from North Koreans who have passed through the facility.

He said they have had to cope with the stress of escape, and the constant fear that they will be caught and sent back before they make it to South Korea.

Many struggle to overcome the guilt of leaving relatives behind in North Korea who they might never see again.

Some face prejudice in South Korea and so choose to hide the fact that they are from the North.

"One of my patients was once having lunch in a restaurant when on the television there was news about North Korea launching a missile," said Dr Jeon.

"He became very uncomfortable, so quickly finished eating and left the restaurant. He was worried about what people would think if they knew he was from the North."

Unification Ministry

Unification MinistryIn an interview with journalists, three female defectors currently at Hanawon gave a hint of the difficulties they are trying to overcome.

They were fearful of revealing their names and were introduced as A, B and C. One woman spoke from behind a screen.

All three had arrived in South Korea after first escaping to China, where their lives were better than in North Korea - but still full of anxiety and danger.

Woman B said she was unable to get a Chinese identity card, which meant she could not go to a hospital, get a bank card or even travel on a train.

Woman C said she was paid half the wages of a Chinese worker because she was in no position to argue for more.

They also described a tightening net of Chinese surveillance that had forced them to seek shelter in South Korea.

"When I first decided to defect I wasn't afraid of anything because I was all alone," said woman A. "But then I had a child in China and realised I had no legal status."

All three women spoke of their hopes - and trepidation - for the future. One of them said she was even worried about paying tax.

Someone who knows what they are going through is Kim Sung-hui, who graduated from Hanawon just over a decade ago and now runs her own business making a rice wine that's popular in North Korea.

In North Korea, Mrs Kim had been told that the South Koreans would initially welcome her - and then she would be tortured and killed.

"It wasn't until I graduated from Hanawon that I finally realised that I was safe," she said.

Mrs Kim said the real education for those at Hanawon would begin only after leaving the facility.

"The first night on the outside is a memorable one for all defectors. I felt such relief that I was finally in South Korea. I hugged my daughter and started to cry - not because I was sad or lonely - but because we'd survived," the 49-year-old said.

In those first few weeks on the outside, Mrs Kim remembers the kindness of South Korean volunteers who helped her adjust.

They were there to welcome her when she stepped into her new home, they showed her around the local shops and even paid for her first ride in a taxi. She still keeps in touch with some of them.

Those still at Hanawon will be hoping for similar success.