Winnie the Pooh horror film will not be shown in Hong Kong or Macau

Alamy

AlamyA new Winnie the Pooh horror movie will not be released in Hong Kong and Macau, its distributor has said.

VII Pillars Entertainment apologised for the "disappointment and inconvenience" to viewers in the Chinese special administrative regions.

The film was released in the US in February and across the UK in March.

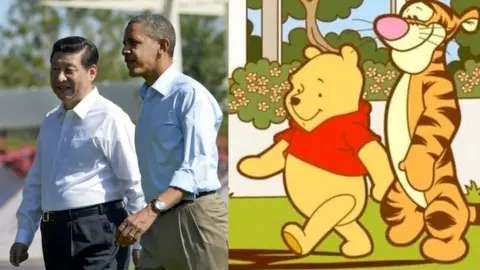

References to the original, family-friendly version of Winnie the Pooh have been used to protest against President Xi Jinping in recent years.

The meme began after an image showing China's President Xi Jinping and former US President Barack Obama began circulating in 2013.

Censors in China have since clamped down on references to AA Milne's character, and the 2018 Christopher Robin film was banned in the country.

AFP/Weibo

AFP/WeiboHong Kong's Office for Film, Newspaper and Article Administration denied the film had been censored, saying it had issued a certificate of approval for the horror movie.

The office told Reuters it would not comment on commercial decisions made about the movie.

The film's director Rhys Frake-Waterfield told Reuters: "The cinemas agreed to show it, then all independently come to the same decision overnight. It won't be a coincidence.

"They claim technical reasons but there is no technical reason. The film has showed in over 4,000 cinema screens worldwide. These 30-plus screens in Hong Kong are the only ones with such issues."

The horror movie has received a score of just 4% on film rating site Rotten Tomatoes. It depicts the bear, known for being kind and honest, as a vengeful axe wielding half-man, half-bear.

It went viral online when the trailer was released.

Frake-Waterfield was able to make the film when the 95-year copyright on Milne's first Winnie the Pooh story elapsed in the US in January last year.

But Disney - which bought some licences in the 1960s - still owns certain rights. Trademark laws mean the bear cannot wear a red T-shirt in the horror film, for example.

"We weren't allowed to have him say things like 'oh bother' either," Frake-Waterfield told BBC Culture last month.

"There are these elements where we need to be careful not to encroach on their brand and their territory because that's not the intention.

"The intention isn't just to steal their copyright and use it for our own purposes. It's to go from something which is possible to use because it's now publicly available, and just go off on an extreme tangent from that point and make this horrific alternative version to him."