Bangladesh accused of violent crackdown on free speech

BBC

BBC"I was treated like an animal in a zoo. I was permanently blindfolded - the only time they removed my handcuffs from behind my back was to eat."

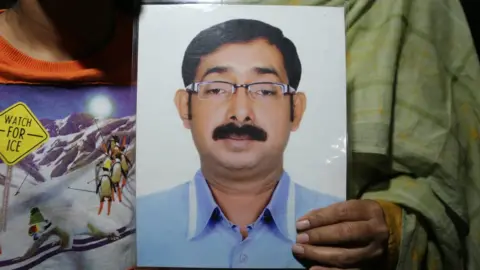

Bangladeshi journalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol, known as Kajol, says he was held in an underground cell for 53 days, where he alleges he was tortured.

"Sometimes they would beat me before they took me for an interrogation. I can't put into words how painful it was.

"They'd asked me about the stories I had written. I had to face a lot of torture. I still struggle to speak about it."

The BBC is unable to independently verify Kajol's account.

"There are no human rights in this country," the 54-year-old says, speaking to us from a secret location. "I live in continuous fear."

Kajol chose to talk to us in the same week security forces clashed with members of the opposition Bangladesh National Party (BNP) in the capital Dhaka, and a mass anti-government rally was held on Saturday - the country's Human Rights Day.

The BNP had urged people to take to the streets to demonstrate against the government led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and her Awami League party. Among their main concerns are calls for free and fair elections, worries over the rising cost of living, and reports of human rights abuses.

In the run-up, opposition officials were detained by police, in what critics say was a direct attempt to crush any form of dissent.

Bangladesh's government denies it is cracking down on freedom of expression.

AFP

AFPIn an interview with the BBC, the country's Foreign Minister Abdul Momen dismissed suggestions his government was stifling free speech, stressing that his nation, formed in 1971 after a war with Pakistan, was founded "to uphold democracy, human rights, and justice".

When Kajol went missing in March 2020, the United Nations was among the organisations which voiced concerns. In a statement it said "the targeting of investigative journalists like Shafiqul Islam Kajol raises serious questions about Bangladesh's commitment to a free and independent media".

The day before he disappeared Kajol had published an article detailing allegations of a sex-trafficking ring involving politicians. Soon after, his lawyer said a member of the ruling Awami League party filed a case against him and others over the story.

The next day, after dropping his son home from school, as he left his office on his motorbike he says he was followed by a group of eight to 10 men on their bikes. Kajol says he was shoved into a minivan and taken to the underground cell.

During his interrogations, Kajol says he was tied to a chair. "They asked me why I wrote about the scandal. It went on for five to six hours at a time. It was a horrible experience."

In a statement, Bangladesh's home minister told the BBC that Kajol had been arrested for editing photos of some girls and publishing them on social media as a form of harassment. "Those girls made a complaint to the security forces against Shafiqul Islam Kajol. Then the security forces arrested Kajol and produced him before the court the next day according to law."

The minister also denied that Kajol was held in an underground cell for more than 50 days.

Human Rights Watch says it has heard evidence of the existence of secret detention sites in Bangladesh, and has called on the government to investigate these allegations and release anyone still being held at them.

"We have heard they are often underground, with very little natural light. Some people have said they can hear other people being tortured. It's very disturbing," Meenakshi Ganguly, the organization's South Asia director told the BBC.

The government denies their existence.

Months later, having been moved to two other cells in the same location, this time not underground, Kajol says he was dumped in a field close to India, still tied up and blindfolded. There, he was picked up by border officials and taken to a jail where he spent a further 237 days before, after 13 appeals, he was released on bail in December 2020.

While he was in jail, Kajol was charged with defamation under Bangladesh's digital security act (DSA), a law critics say is draconian and criminalises any sort of dissent online - including sharing a Facebook post that might be considered critical. Since it came into law in 2018, thousands have been charged.

Human Rights Watch says Kajol's ordeal is typical of tactics used by security forces to silence criticism of the government.

According to Bangladeshi human rights groups nearly 600 men have been victims of "enforced disappearances" by the Bangladeshi security forces since 2009.

The United Nations working group report published in August 2022 said there were 72 victims of enforced disappearances, who remain missing in the country.

Foreign Minister Momen dismissed these numbers, claiming that the figures collected by the UN came from "some quarters who are politically motivated". He accused local groups who collate the figures of "magnifying" and "doctoring" information.

But the families of those who are still waiting for their relatives to return say the stories they are living through are very real.

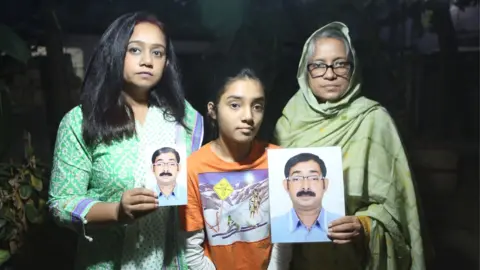

Sajidul Islam Shumon, a local party organiser for the opposition Bangladesh National Party, was last seen in December 2013.

With a general election just weeks away in January 2014, fearing intimidation from the Awami League government, he temporarily moved away from home for the safety of his family.

One day they heard from witnesses that Sajidul had been rounded up, handcuffed and blindfolded by security forces from the elite paramilitary Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), before being shoved onto a bus with a group of men.

His sister Sanjida had seen him a few days earlier, when he popped home to see the family, in particular his one-year-old daughter Arwa.

"It was cold as it was December, so I gave him a light blue hoodie to wear outside," Sanjida said, recounting their final hug goodbye.

"That's the last thing I gave to him. I don't even know if he was able to wear it or not."

Arwa is now 10 years old, and every time Sanjida shows her a photo of her father, she kisses the glass frame, asking when her daddy will return.

Sanjida now runs a support network, Mayer Daak, for the dozens of other women who say they have also lost their brothers, husbands, sons and fathers to enforced disappearances.

Many of the families have lost their sole breadwinner, and are struggling with poverty on top of their personal pain.

Some, including Sanjida, said they would take to the streets of Dhaka this weekend to join the anti-government protests, as they continue to seek justice.

Sanjida and other relatives say they have tried to file cases for their missing relatives at the police station, but were turned away unless they removed any mention of the involvement of government security forces.

Her mother - now in her seventies and unwell - used to go to the police station every week to try to file a case for her son.

The family refuse to give up hope.

"Until we know what happened with him we can't decide if he is alive or not."

Additional reporting by Aamir Peerzada.