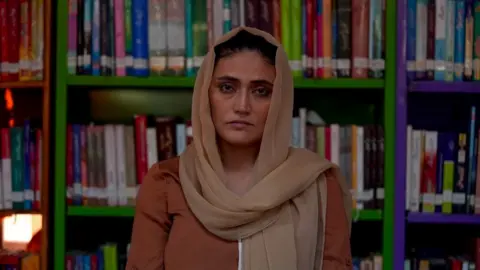

The librarian who defied the Taliban

BBC

BBCWahida Amiri worked as an ordinary librarian before the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan last August. But when the militants started to strip women of their rights, she became one of the leading voices against them. She told the BBC's Sodaba Haidare how protesting against Taliban rule led to her arrest and why she decided to leave her country.

The Taliban said I was a spy. That I had helped start an uprising against them. That I went onto the streets and protested just to get fame. "Go home and cook", said one of them.

But the truth is, I only wanted one thing: equal rights for Afghan women. The right to go to school, to work, to be heard. Is that too much to ask for?

The day they came to arrest us, an eerie silence had fallen over Kabul. In recent days a number of women who had protested against the Taliban had been taken, so we were moved to a safe house.

In the last few months since the Taliban took over Afghanistan, I had been a strong and proud woman, marching through the streets to protest against them. I looked them in the eye and said: "You can't treat me like a second class citizen. I'm a woman and I'm your equal." Now, I'm hiding in this unknown place, not knowing my crime but wondering if they'll come for me.

Suddenly, tires came screeching and broke to a halt outside the building. I couldn't count the number of cars or soldiers. It seemed they had come prepared to arrest a whole village and not just a few women marching to live freely in their own country.

When they barged into the room, in the middle of all my friends' screams and panic I could hear them say: "Have you got Wahida Amiri, have you found her? Where is she?" I thought: "This is it. It's over, I'm going to die."

The library was my happy place

Before the tragic day of 15 August 2021, I was an ordinary woman. I had graduated with a law degree and now at 33 years old I ran a library in the heart of Kabul.

The library was my happy place where everyone was welcome, especially women. Sometimes we discussed topics like feminism over chai sabzi, the traditional Afghan green tea with cardamom. Afghanistan wasn't perfect, but we had freedom.

I cared deeply about books because up until the age of 20 I couldn't read myself.

I had just started school when the Taliban first rolled into Afghanistan, waving their black and white flags. The year was 1996.

One of their first orders was to shut schools for girls.

All our relatives fled to Panjshir, a mountainous valley in the north and our original home. But my father decided to stay and after my mother died, he remarried. The years that followed were extremely painful.

Reuters

ReutersWe moved to Pakistan where all the chores and responsibilities in the house fell on my shoulders. I cooked, cleaned and scrubbed the floors all day long. I thought this would be my life. Then came September 11, 2001.

I watched the fall of the twin towers on TV. It wasn't until much later that I properly learnt about 9/11 and how much that day changed the lives of ordinary Afghans like us. Before long we waved goodbye to Pakistan. The Taliban had been defeated and it was safe to go home - we'd never be refugees again and I'd never come back here, that's what I thought.

I was 15 when we moved back to Kabul and I saw how different life was now that the Taliban were not in charge - girls were going to school, women could work. But not much changed for me. To my family keeping the house tidy and serving guests was more valuable than my education - so I carried on running a house until my cousin helped me to enrol back into a school some five years later.

The letters in the books were shaped strangely - the words looked back at my face blankly. I took exams and scrubbed floors at home at the same time. And every time I failed I would try again and again, until I passed.

When by some miracle I got accepted into university to study law, I was still a shy and timid girl - until a woman came into my life. Her name was Virginia Woolf. Her manifesto was A Room of One's Own. I felt like I was reborn. The book of this important English author taught me everything I should have known a long time ago. The more I read, the more I realised that I was a strong woman with my own thoughts.

The fall of Kabul

On a hot day in August, the nightmare I had lived through once returned to my life. The Taliban drove into Kabul waving the same black and white flags.

Only this time it wasn't 1996, it was 2021. And I wasn't a child. I wasn't uneducated. I had gone through hell to build a life, and I wasn't going to hand it over to them just like that.

I was relieved when I found other women had the same thoughts. We knew the risks of defying the Taliban but we all said "let's protest". We came up with a name for our group: Spontaneous Movement of Fighting Women of Afghanistan.

Wahida Amiri

Wahida AmiriAt this point the Taliban had already shown their true colours. They backtracked on their promise to allow women to return to work and shut schools for girls once again. They announced their new "government" and there was not a single woman in it.

In those first days, as we marched on the streets for our rights, the Taliban cornered us. They fired teargas at us, and shots in the air - they even beat some of the women. Then they banned protests altogether.

Most of the women decided not to carry on, it was too risky. But they couldn't stop me.

I continued organising protests. The night before each one I couldn't sleep. I'd be restless and scared. I'd keep thinking "tomorrow will be the last day of my life".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe arrest

In Afghanistan, arresting a woman is the same as ruining her reputation. There's a general assumption that she's been raped and in the Afghan society, it's the worst kind of shame a woman will carry.

That day in February 2022, when the Taliban stormed into the safe house to arrest us, we were ordered to hand in our phones. I couldn't breathe. "What's next?" I thought. "Will they kill me? Gang rape me? Torture me?" I felt like I had a body but my soul had left me.

We were put in their pickup trucks and taken to the Ministry of Interior Affairs. We passed a long hallway with a red carpet and were led to a small room that used to be the ministry's nursery, though it didn't look like one. No paintings, no toys, just a few national flags of Afghanistan piled up in the corner and a giant map of the country on the wall. We'd be kept in this place for the next 19 days.

The day after our arrest, one of the Taliban pushed the door open and stormed in. He was tall and had a dark expression. His eyes scanned the room and when he found me he shouted abusive words - he said I was "dirty" and "impure". "You've been insulting the [Islamic] Emirate for the past six months. Who are you collaborating with?"

I told him: "No-one, I'm doing it all on my own." Then he handed me a pen and piece of paper and said "You're a spy. Write down the name of all your collaborators."

Wahida Amiri

Wahida AmiriSince I was from Panjshir, a province known for resisting against the Taliban, they thought I was being supported by the National Resistant Front, an armed group that is fighting them in the north.

The days that followed were slow. One by one the other women were released, but not me. Then one day they brought in a camera and told those of us remaining that they were going to ask us questions and we were to answer them looking at the lens.

When we demanded to know what the recording was for, they said it was just a formality and would be kept in the ministry's archives. We were told to say our names, which province we were from and who was helping us. By force they made us say Afghan activists abroad told us to protest.

We didn't know at the time but this would give people the impression that we marched to become famous and be evacuated from Afghanistan.

Shortly after, they released the forced confessions to the media. In a small TV in the hallway we saw the video being played by Tolo News, one of the largest TV stations in Afghanistan.

We all broke down crying. Now everyone knew we were taken by the Taliban. They didn't rape us, but in the eyes of many people they had. Now everyone thought we protested just to get help to leave Afghanistan.

Two days after the forced confessions they said we were free to go. It came with a price, though - we had to promise not to protest again.

Kabul was cold, the streets were empty.

On the way home, my eldest brother couldn't stop scolding me. "What were you thinking, Wahida? Did you really think you could bring the Taliban down? You're just one woman." I was ashamed. I had lost everything. My job, my freedom and now the meaning of my life if I couldn't protest anymore.

One day I read an anonymous interview with another female protestor who said the Taliban had beaten us while we were in their custody. They hadn't. My family begged me to leave Kabul as they were worried the Taliban would be angered by the article and come for us again.

So, two months after my release I packed a small bag of clothes and some of my favourite books, including A Room of One's Own, and said goodbye to my motherland.

I left home at the crack of dawn and once again ended up in Pakistan.

I left my whole family. I left my bookshelves. I left the library. The last time I was there was the 14th of August, one day before the fall of Kabul. I sometimes wonder what happened to those books - are they still there?

I was a librarian in my previous life, now I am a refugee.

A new life

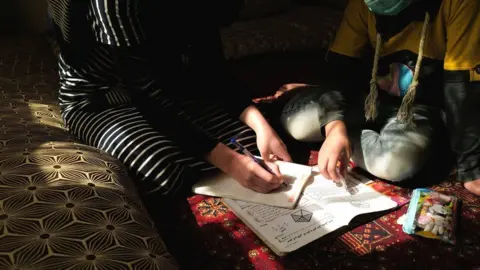

I live with a number of other families in Pakistan. I stare at my books but I don't have the energy to flick through the pages. I feel trapped like I can't dream or escape to another reality, even if it's just for a moment.

The women still in my country are being silenced with many afraid of opposing the Taliban openly. I go to the park to clear my head but the thought of my people doesn't leave me. I miss my home, my family and my cat.

The only thing that gives me a little joy and reminds me of home is an Afghan restaurant nearby.

These days I spend a lot of time in the local library, trying to put some words together about the women who protested. About our lives and how much they changed because of the Taliban.

I hope what I'm writing could one day turn into a book. I want women around the world to know Afghan women didn't just give up, they fought and when they were silenced and defeated they rose again, in one form or another.

I spend the rest of my time speaking to Afghan women all over the world - from Germany to the US - organising a global movement against the Taliban.

My aim is to make sure the international community never recognise them as an official government. I want them to put pressure on the group to reopen schools, to let our girls learn, to let us live freely in our own country.

I've wasted too much time not being able to read. To this day there are certain letters I still can't pronounce the way I should. I don't want the same for the future generations of my country.

Photos by Munazza Anwaar and Musa Yawari.

BBC 100 Women names 100 influential and inspiring women from around the world every year. Follow BBC 100 Women on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter. Join the conversation using #BBC100Women.