Nepal: Return of the tigers brings both joy and fear

Deepak Rajbanshi

Deepak RajbanshiNepal has pulled off the extraordinary feat of more than doubling its tiger population in the past 10 years, bringing them back from the brink of extinction. But it has come at a cost to local communities - an increase in tiger attacks.

"There are two feelings when you come head to head with a tiger," says Captain Ayush Jung Bahadur Rana, part of a unit tasked with protecting the big cats.

"Oh my God, what a majestic creature. And the other is, oh my God, am I dead?"

He now often sees Bengal tigers on the armed patrols he carries out across the open plains and dense bush of Bardiya, the largest and most undisturbed national park in Nepal's Terai region.

"Being assigned to tiger protection duties is an honour. It's a privilege to be part of something that is really big," Capt Ayush says as he glances around through the thick forest.

Kevin Kim/BBC

Kevin Kim/BBCNepal's zero-poaching approach has worked to protect the tigers. The military units support the national park teams. And in buffer zones next to the park, community anti-poaching units monitor nature corridors that allow tigers to roam safely.

One such strip of land, the Khata corridor, links Bardiya National Park with the Katarniaghat Wildlife Sanctuary across the border in India.

BBC

BBC

But the return of the tigers has created life-threatening challenges for people on the border of the park.

"The community lives in terror," says Manoj Gutam, an eco-business operator and conservationist.

"The common area that tigers, prey species and humans share is so tight. There's a price the community has paid for the world to rejoice in Nepal doubling its tiger numbers."

In the past 12 months, 16 people have been killed by tigers in Nepal. In the previous five years, a combined total of 10 people were killed.

Deepak Rajbanshi

Deepak RajbanshiMost attacks occurred when villagers went into the national park or the buffer zones to graze cattle, or collect fruit, mushrooms and wood.

In some cases tigers have emerged from the national parks and nature corridors, venturing into local villages. There are fences to separate wildlife and humans but the animals have been able to get through.

Kevin Kim/BBC

Kevin Kim/BBCBhadai Tharu has more than just battle scars from the beloved tigers he is helping to conserve. In 2004 he was attacked while cutting grass in the community forest near his village. He lost an eye.

"The tiger jumped at my face, making this huge roar," he says, acting out the scene.

"I was thrown back instantly. Then the tiger hopped back like a bouncing ball. I punched him with all my strength and cried out for help."

When he takes his aviator sunglasses off, something he rarely does, it reveals deep scars and his missing eye.

"I was angry and sad. What did I do wrong as a conservationist?" he recalls. "But tigers are endangered animals, we have a duty to protect them."

The recent history of tigers has been bleak.

A century ago, there were about 100,000 wild tigers spread across Asia. By the early 2000s, that number had plummeted by 95%, largely because of hunting, poaching and loss of habitat. There are now thought to be between 3,726 and 5,578 tigers left in the wild according to International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Spread over 968 sq km (374 square miles), Bardiya became a national park in 1988 to protect endangered wild animals. The region was once a royal hunting reserve.

In 2010, 13 countries where tigers live pledged to double their wild tiger populations by 2022 - the Chinese Year of the Tiger - in an effort to bring them back from the brink of extinction.

Only Nepal has so far reached the target.

The tiger population in Nepal has grown from 121 in 2009 to 355 in 2022. The big cats can mainly be found in five national parks across the country. Other species including rhino, elephant and leopard populations have also increased.

Deepak Rajbanshi

Deepak RajbanshiTo maintain a healthy population of wild tigers park authorities have created more grasslands. They have also increased the number of waterholes to create an ideal habitat for deer, the tigers' main prey.

Chief warden of Bardiya National Park, Bishnu Shrestra, denies these human interventions, which have helped the tigers to thrive, are pushing things too far.

"We now have sufficient space and prey density in the park, so we are managing the tigers in a sustainable way," he insists.

BBC

BBCTigers are making a roaring comeback in Nepal. Rebecca Henschke investigates.

BBC

BBCPeople living near Bardiya National Park have largely supported the conservation efforts but as the tiger numbers grow there is increasing unease.

"Tourists come to see the tigers, but we [have to] live with them," says Samjhana, who lost her mother-in-law in an attack last year. She had been cutting grass to feed their cattle deep inside the park boundary.

"I loved her more than my own mother," she says through tears as she holds the only photo she has of her.

Kevin Kim/BBC

Kevin Kim/BBC"During the next few years more families will suffer like me, and the number of victims will soar," warns Samjhana.

As well as coming onto farmland, tigers have also ventured into the nearby villages.

In March this year, Lily Chaudhary, who lives in Sainabagar village on the edge of the Bardiya National Park, went to feed her pigs, close to her house.

Villagers found her seriously wounded by a tiger, with her lower limbs mauled. She died soon after.

"Since then, we are all scared to go alone to feed the pigs or cattle in the backyard," says Asmita Tharu, Ms Chaudhary's younger sister.

Deepak Rajbanshi

Deepak RajbanshiBig cat attacks have prompted protests by local people.

On 6 June, people rose up in Bhadai Tharu's village after a leopard attacked Ashmita Tharu and her husband, a week after a tiger killed someone in a community forest nearby.

About 300 people took to the streets demanding authorities do more to protect them.

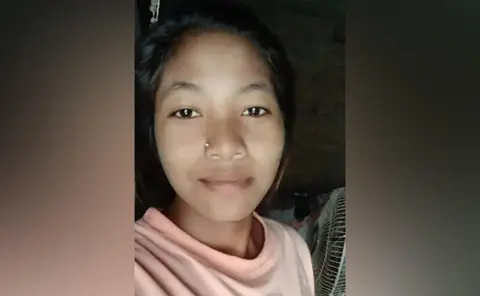

The crowd burnt down the community forest office. When police arrived, rocks were thrown at them. Security forces then fired at the crowd killing teenager Nabina Chaudhary, the niece of the couple attacked by the leopard.

Her brother Nabin Tharu was a few metres away from her when it happened.

"I wanted to take her body off the road but the police were beating people," he says.

"My sister did nothing wrong. Is demanding security wrong? Is demanding safety wrong?"

Nabin Tharu

Nabin TharuThe Nepalese government has promised Nabin's family $16,000 (£13,000) in compensation and has said they will build a statue of her describing her as a martyr. But the family are demanding a full investigation.

In an agreement signed with the local community after the unrest, authorities have vowed to look into building more fences and walls in an attempt to divide humans and wildlife.

- Listen to the podcast: Return of the Tigers

In Nepal, when a tiger kills a human, the animal is tracked down and taken into captivity. There are currently seven so-called man-eating tigers behind bars.

"I would say tiger protection is our responsibility, at the same time protection of people is our duty," says Capt Ayush Jung Bahadur Rana as he heads back to base.

"A greater number of tigers and a greater number of people, [means] definitely there's going to be conflict. It's going to be challenging to maintain peace between two species."

Officials are looking at providing alternative livelihoods for those who use the national park to collect materials or graze cattle. They plan to develop skills so locals can start small businesses or work in tourism.

Kevin Kim/BBC

Kevin Kim/BBCBhadai Tharu calls a meeting of his local tiger protection team.

"A misunderstanding divides humans and wildlife," he tells them.

"Our forest is the tigers' home. If we intrude into their habitat, they will get angry. If we allow goats to graze in the forest, then they will attack."

His team is making plans to create more secure stables for livestock and to make more grassland in the community forests, adjacent to the park so the tigers will have plenty of deer to eat.

They also run classes for the next generation which will have to live with the return of the tigers. Children are taught about tiger behaviour and told not to go into the forest alone. When asked what their favourite animal is, many children would say a tiger.

"I try to help people understand that tigers have a right to live here," says Bhadai.

"Why should it be only humans?"

Additional reporting Rama Parajuli, Kevin Kim, Rajan Parajuli and Surendra Phuyal

Photographs subject to copyright