Sri Lanka crisis: How war heroes became villains

AFP

AFPSri Lankan President Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled the country in the early hours of 13 July - a humiliating exit for a man whose family had been in power for nearly two decades.

Days before, hundreds of protesters had stormed his official residence, demanding that he resign over Sri Lanka's economic crisis, which has seen no respite in months. The country is still out of cash, daily power cuts are routine, and supplies of fuel, food and other essentials like medicines are close to running out.

Sharply rising prices had set off mass protests in April, and the growing anger forced Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa - the departing president's elder brother - out of power in May.

He resigned after his supporters attacked anti-government protesters, triggering deadly clashes across the country. Dozens of houses of politicians were torched, including some owned by the Rajapaksas. Mahinda had to be evacuated from his official residence after it was besieged by angry crowds.

But his departure did nothing to ease the growing pressure on his younger brother, 73-year-old Gotabaya.

He held on as president, ignoring calls to quit, although he was forced to offer some concessions. He transferred some his executive powers to parliament, and appointed a veteran, Ranil Wickremesinghe, as the new prime minister heading a proposed cross-party government.

The news was met with shock and anger - Mr Wickremesinghe, who had served five times as PM but never completed a full term, is seen as a close ally of the Rajapaksas.

As the economic crisis dragged on and ordinary Sri Lankans struggled for everything, from fuel to food, the protests began to gather pace again. They erupted on 9 July, when thousands of people marched their way into the palatial official home of the president.

Reuters

ReutersHe was whisked away to a safe location - in much the same way as his brother was in May, reportedly finding sanctuary at a naval base in the north-east.

Gotabaya flew on a military plane to the Maldives and, according to sources, was trying to make his way to an as yet unspecified final destination. But although he left the country he did not immediately resign, and critics said he was clinging to power until he was safely somewhere he could not be extradited to face justice in Sri Lanka.

How did the Rajapaksas, once hailed by many Sri Lankans as heroes, come to be reviled as leaders?

Mahinda Rajapaksa was once celebrated by the majority Sinhalese as a hero for bringing an end to nearly three decades of civil war when the Tamil Tiger rebels were crushed in 2009 during his first term as president.

He was compared to Sinhala Buddhist kings at victory parades and mass public events.

"He was the most popular Sinhala Buddhist leader in post-independence Sri Lanka. Some even hailed him as Emperor Mahinda," says veteran political analyst Kusal Perera.

In his 2017 book Rajapaksa: The Sinhala Selfie, Mr Perera highlights the Rajapaksa family's role in the island's politics and how Mahinda groomed himself for power.

His father was a parliamentarian and Mahinda gradually rose from opposition leader in parliament to prime minister in 2004.

When he became president a year later, he made Gotabaya defence secretary. It was a big career jump for the former Sri Lankan military officer who was living a quiet life in the US after retiring.

Gotabaya returned for his brother's campaign and rose to prominence, earning a reputation for ruthlessness.

AFP

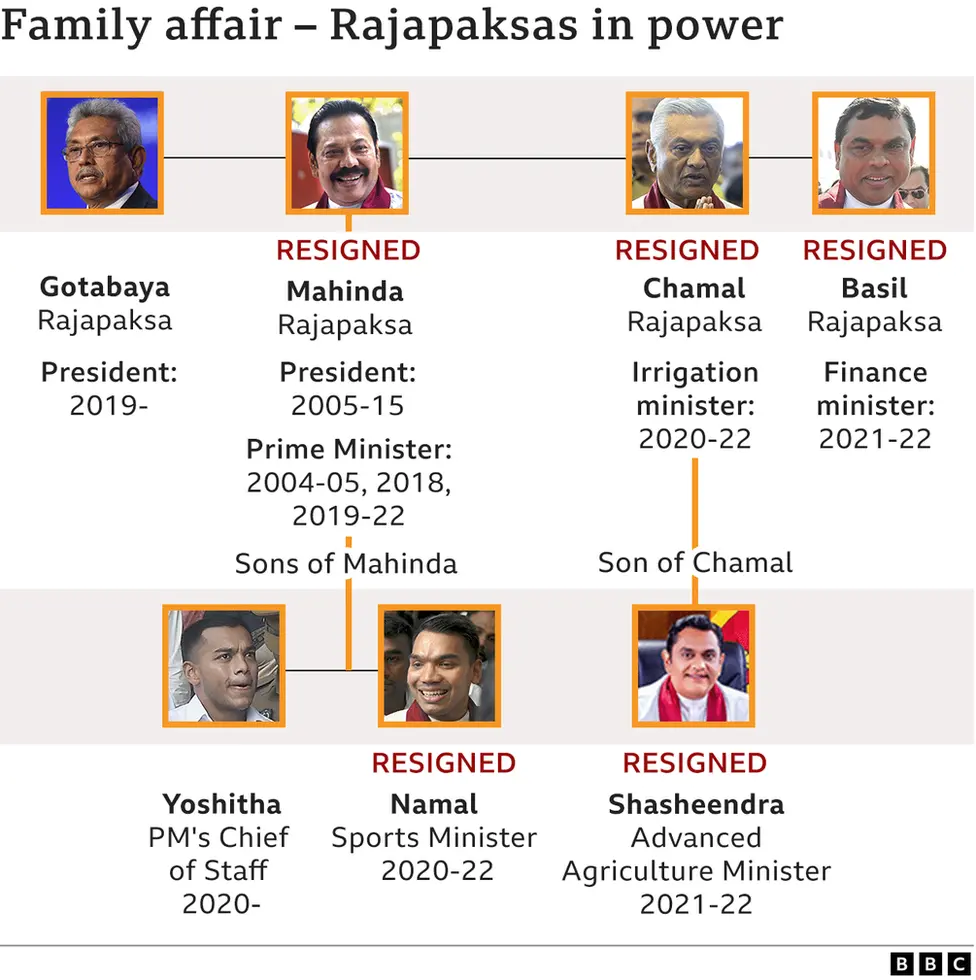

AFPSoon, others from the family joined the government. It was Mahinda, the family patriarch, who was instrumental in establishing the Rajapaksa political dynasty.

Until the unprecedented protests this year, the brothers had always stood together. But cracks started to appear when Gotabaya asked Mahinda to "take one for the team" and heed protesters' calls to resign.

The demand was a huge snub for a man who brought his younger brother into government - and certainly not the way he wanted to end his political career.

"He was basically pushed to the wall and forced to leave in a huge youth protest that he fumbled in handling. His age will hold against his return," Mr Perera says.

Mahinda's eldest son, Namal, denies the brothers have a problem.

"Definitely there is a policy difference between the president and the [former] prime minister," he had told the BBC a week before Mahinda's resignation.

He said his father had always supported farmers and the poor, while Gotabaya Rajapaksa had a different approach "looking more into the floating vote rather than the masses or hardcore SLPP [governing party] vote".

Gotabaya Rajapaksa had reportedly told people close to him that he wasn't interested in a second term but wished to lead the country out of the current economic crisis.

Reuters

ReutersBut the growing anger against the family - who many Sri Lankans squarely blame for the country's economic woes - left no room for that.

The Rajapaksas were hugely popular among the Sinhala community for years, despite allegations of serious human rights abuses and discrimination against minorities. They were also blamed for murderous attacks on the media. But few Sinhalese spoke out against the influential family.

It's a different story now as the economic crisis has united many Sri Lankan communities, with Sinhalese protesters even voicing support for minority rights.

"The economic hardship really hit the majority community and suddenly they turned. I think the Rajapaksas who were able to get away with so much for decades were surprised to see this level of anger," says Bhavani Fonseka, a human rights lawyer.

The continuing political stalemate is likely to worsen the country's economic troubles. Without a stable government, it will be difficult to negotiate a loan with the International Monetary Fund or restructure debt.

"Regardless of who runs this country, we just need our basic needs to be met," says Chandani Manel, who lives in Colombo.

"I have two children to feed and a family to look after. Politicians can survive with their wealth but not us," she says.